Napoleon's Chinese whispers

Published on

Translation by:

Sarah TruesdaleHow western Europeans use the word 'China' to express being stressed, arrogant or insignificant

Napoleon was not one to chinoiser  (‘to split hairs’ in French), or to beat about the bush. No, he was rather more likely to put his foot in his mouth. And there were those in Germany (well, in Prussia at least) who thought that he even fancied himself as ‘the emperor of China’ (‘sich für den Kaiser von China halten’

(‘to split hairs’ in French), or to beat about the bush. No, he was rather more likely to put his foot in his mouth. And there were those in Germany (well, in Prussia at least) who thought that he even fancied himself as ‘the emperor of China’ (‘sich für den Kaiser von China halten’  in German). Of course, in keeping with good military strategy, he had certainly thought about invading the ‘Middle Kingdom’. It would have been a great opportunity to gather some chinoiserie

in German). Of course, in keeping with good military strategy, he had certainly thought about invading the ‘Middle Kingdom’. It would have been a great opportunity to gather some chinoiserie  (‘Chinese art works’) disguised as souvenirs for his family, who were lovers of Ming vases and other trinkets from the Orient. But, given the distance, it would have been a real casse-tête chinois (literally, 'wracking your brains like the Chinese' or ‘pain in the neck’) to organise such an expedition, which was a truly laborious enterprise. In short, a ‘Chinaman’s job’, as is said in Spain (‘trabajo de chinos’

(‘Chinese art works’) disguised as souvenirs for his family, who were lovers of Ming vases and other trinkets from the Orient. But, given the distance, it would have been a real casse-tête chinois (literally, 'wracking your brains like the Chinese' or ‘pain in the neck’) to organise such an expedition, which was a truly laborious enterprise. In short, a ‘Chinaman’s job’, as is said in Spain (‘trabajo de chinos’  ). Moreover, even his best soldier solemnly declared to a surprised Napoleon to have such multilingual men in his charge: ‘I wouldn’t go there for all the tea in China

). Moreover, even his best soldier solemnly declared to a surprised Napoleon to have such multilingual men in his charge: ‘I wouldn’t go there for all the tea in China  .’

.’

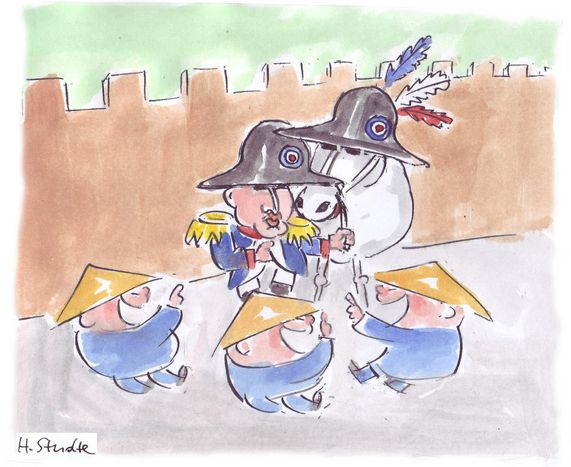

Finally, Napoleon saddled up his horse and travelled alone to the ends of the earth. Once he had passed the Great Wall of China, he felt a bit like a ‘bull in a China shop’  . Everyone had a chapeau chinois (‘a hat and a limpet’) fixed to their heads, pointed at him and made fun of his famous bicorne hat. Talk of this incident spread round the country and even reached the ears of the emperor. Whilst busy taking German lessons, he responded with an irritated air: ‘In China ist ein Sack Reis umgefallen’

. Everyone had a chapeau chinois (‘a hat and a limpet’) fixed to their heads, pointed at him and made fun of his famous bicorne hat. Talk of this incident spread round the country and even reached the ears of the emperor. Whilst busy taking German lessons, he responded with an irritated air: ‘In China ist ein Sack Reis umgefallen’  , as much as to say that the event was of no particular importance. Piqued, poor Napoleon consoled himself by attending a performance of ombres chinoises

, as much as to say that the event was of no particular importance. Piqued, poor Napoleon consoled himself by attending a performance of ombres chinoises  (literally, 'chinese shadows' meaning ‘shadow puppets’) and then returned home.

(literally, 'chinese shadows' meaning ‘shadow puppets’) and then returned home.

Translated from Des mots chinois