My beautiful camp: Italy's Roma success stories

Published on

Translation by:

Tom GaleBetween a Roma camp claiming to be an example of social integration and a laundrette which is a supposed symbol of multiculturalism, profound problems linger at the heart of Rome’s gypsy communities

She hobbles along, walking with a sense of composure, arms crossed. She salutes her neighbours one by one with a fixed stare and a slight nod of the head, while at the same time telling off her children for tossing acorns at a sleeping dog. Her arms remain crossed. Ubizha Halilovic is the mayor of this camp; the confident Roma woman has governed this village of 203 inhabitants for a number of years, with the majority of the camp approving her leadership through polls. Umizha is thus effectively an elected politician. ‘I became the spokesperson of the camp following elections organised by the community,’ she says proudly. Even in a Roma camp in Italy, the relics of an election victory are visible in daily life. While the majority of families live in prefab homes, Umizha enjoys the pleasures of a spacious and solid wooden house, its defining feature being a superb wooden balcony.

Cesare Lombroso

Here in northern Rome, the camp of Bosnian immigrants lives in apparent tranquility. Paradoxically the village has been christened Cesare Lombroso, due to the name of the adjacent road, itself named after an Italian criminologist who claimed that certain population groups, gypsies included, are born criminals in his 1876 book Criminal Man. The scene is set. The Cesare Lombroso camp is the only Roma village within the proximity of the city centre. It is not merely one of only seven camps in Rome which have been authorised by the local authorities, but it is also largely regarded as a model of social integration.

‘Ten years ago, in 2001, the camp was officially recognised by the authorities. Thanks to this the villagers are able to enjoy clean water and electricity in exchange for a commitment to education,’ point out Seresa Masci and Catia Mancini, secretary and coordinator respectively of Arci solidarietà, the organisation in charge of managing the camp. Each of the 34 families at the camp, all of which are from Mostar, have three children on average. Out of 110 children, 83 attend school. ‘If a family chooses not to send their children to school, I throw them out!’ insists Umizha.

The children seem light-hearted: Liban, Brandon and Spider-man (the Roma often name their children after their favourite television shows) are enjoying counting their marbles. The adults share an altogether different reality: ‘If the leadership knows the camp, it knows nothing of the people inside it. They don’t have any immigration papers and they don’t work. In order to survive, a supermarket was opened in the heart of the village selling metals, scrap iron and rubber.’ Despite being only 43, Umizha carries a weathered look, proof of a laboured life. ‘I came to Italy when I was six. I had never travelled. I begged on the street, trying to sell dresses. When I got married, I opened a stall where I sold bits and bobs that I found in the bins. Then I came to the camp in 2001.’

The children seem light-hearted: Liban, Brandon and Spider-man (the Roma often name their children after their favourite television shows) are enjoying counting their marbles. The adults share an altogether different reality: ‘If the leadership knows the camp, it knows nothing of the people inside it. They don’t have any immigration papers and they don’t work. In order to survive, a supermarket was opened in the heart of the village selling metals, scrap iron and rubber.’ Despite being only 43, Umizha carries a weathered look, proof of a laboured life. ‘I came to Italy when I was six. I had never travelled. I begged on the street, trying to sell dresses. When I got married, I opened a stall where I sold bits and bobs that I found in the bins. Then I came to the camp in 2001.’

Roma living in luxury

Does the winning formular that Umizha and the others seem to have discovered work for the other Roma? ‘Not at all,’ according to Massimo Converso, president of the opera nomadi association, created in 1963 to help the Roma population integrate into society. Converso, wearing a tracksuit, meets me in the cellar of the association headquarters. ‘In Italy, 90% of the Roma have official papers. This is not the case in Rome. It should not be looked upon as a beacon of integration.’ In three sentences, Converso reels off examples of problems with expulsions, papers, housing...‘OK. The blame is shared,' he adds, in the face of scepticism. 'On the one hand, the Italian government does not want to recognise the Roma’s right to own land. However, I know the Roma. They are also to blame for these worries over integration. I can tell you that some of them live a life of luxury. In the south of Rome, lots of Serbs live in lavish houses. It’s all in a study that was published fifteen years ago by Ratko Dragutinovic called Kanjarija. History of the Dasikhane Roma Living in Italy ('I kañjarija. Storia vissuta dei rom dasikhanè in Italia'). He describes the splendour in which his compatriots decided to live their lives.’

Converso is familiar with the Cesare Lombroso camp. He calls their elections ‘a farce’, the camp ‘a theatre’, the association which manages it ‘a lobby’ and says that its inhabitants? ‘steal copper’...‘The children don’t go to school; the families have a judicial waiver,’ he explains. As far as he is concerned, the paragon of success is his own baby. Baxtalo drom’(literally ‘the happy path’) is a laundrette managed by Roma women that opera nomadi created with help from the vatican.

Thanks to politicians

This is all difficult to pick apart. However with regards to the context neither Cesare Lombroso nor baxtalo drom seem to be representative of the social reality. One needs only to take a step outside to realise that both are peace havens. 4, 950 Roma live in the periphery of Rome in the frail retreat of camps which are either partially tolerated (the case for fourteen camps) or illegal (true of eighty camps). Since the launch of the nomad plan, the Roma have been living like dogs. Launched by an initiative of the Rome prefect on 31 July 2009, the operation aims to install a legal framework which will allow for the expulsion of Roma immigrantsin all impunity, arriving at a final quota of 6, 000 residing in Rome. However, a report by Amnesty International points out that there are some twelve to fifteen thousand Roma living in and around the Italian capital. Thus half face expulsion.

Umizha is right to campaign against ‘ignorant’ politicians but is mistaken in her fight: her camp exists, hypocritically, thanks to politicians, because this camp remains and will remain a calculated pretext to deport her compatriots en masse. For Rome’s mayor Gianni Alemanno and many others, the Cesare Lombroso camp will always keep its initial remit from a criminologist who claimed that the Roma are born criminals.

This article is the first in cafebabel.com’s 2010-2011 feature focus on multiculturalism in Europe. Thanks to the team at cafebabel.com Rome, with special thanks to Gianluca Martelliano

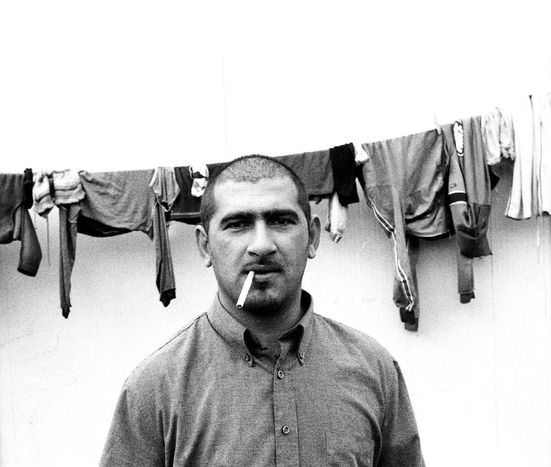

Images: main (cc) Francesco Paraggio/ Flickr ; mayor's house, US flag and Umizha © Matthieu Amaré ; Converso © Ehsan Maleki; laundrette © Opera Nomadi; Video: ermelindacoccia/youtube

Translated from Italie : sur la route du Rom des camps