‘Million Dollar Baby’ Istanbul - no hurdle to being a woman in sport

Published on

More Turkish female athletes - 66 - are participating in the olympics games in London than male - 48. ‘The difference between men and women is that Turkish men don’t really like sports - they just like winning,’ sighs one Turkish friend in Istanbul, which is also the European capital of sports in 2012

Are Turkish women more ‘fair’ in sport than men? Does it explain the female success? Are they better at ‘teaming’? Out of the 66 female athletes in London for the olympic games between 27 July and 12 August, 24 of them are members of basketball and indoor volleyball teams. ‘For sure we are more fair and objective than males,’ says Nursen, a 56-year-old Fenerbahce football fan who attended the children-and-women only match between Manisaspor-Fenerbahce in 2011. ‘We do not have any prejudices. We do not have the intention of fighting before the game. We just want to watch and support our team and get the joy of life while we are at the stadium.’ But women must love winning, too. Where is the competition without the will to fight and win?

Female fighter

I hop on a ferry and sweat my way through a bus ride to Kavacık, Istanbul towards the MMA Corvos Gym. ‘I have had some guys talking to me on the phone for hours about how they want to become a fighter, but when I tell them where the club is, they say it is too far away,’ says founder Burak Deger Bicer, who welcomes me with open arms and a delicious cup of coffee. ‘And they just live 3km across the bridge. Suzan comes from more than 30km away, with public transport.’ Suzan Özen is a female fighter who found out about the gym online. Just like in the movie Million Dollar Baby (2004), the 28-year-old set one foot inside the gym and proclaimed: ‘I want to be a fighter’.

As she wrestles and rolls over the mat with men during Brazilian ju-jitsu training later, nobody seems to mind. She is wearing make-up and has the raven-logo of the gym tattooed on her upper arm, just like some other members. She flashes a big, beautiful smile at me and as Burak translates her first sentence, I can already tell Brazilian ju-jitsu is what she lives for. ‘I have been searching for something all my life and now I have found it,’ she says. ‘It is that kind of long-awaited happiness. My goal is to make this my profession, but it is hard to find sponsorship and money to compete at international tournaments. Even though my family is from the east and they live a village life, they are different, they support my choice. My father said: ‘When my daughter does something, she knows what she is doing’.’

'Some guys will accept wrestling with girls, love the sport for it and train. And some guys hate it, feel bad about themselves and leave'

‘There is generally a lot of prejudice about martial arts in Turkey,’ adds Burak. ‘That’s especially if you are a woman, and if it involves grappling and close contact. But we do not judge people. We do not care if you are rich, poor, a boy or a girl, we just look at techniques. We are not thinking about breasts, we are thinking, maybe she has shorter legs, and so on. People who do feel uncomfortable are often beginners. Sometimes I let guys that walk in my club wrestle with Suzan, to show the effectiveness of what we do. She can fight with a guy twice her size and she could win him over. Some guys will accept this situation, love the sport for it and train. And some guys hate it, feel bad about themselves and leave. That is just the way it is.’

Headscarf run

In Belgrade Forest, 15km north-west of Istanbul, Reyhan and Nergiz kindly offer to share their breakfast with me. The German and English language teachers are hiking and biking on ther day off. ‘Our friends think we are crazy,’ they laugh. ‘Most of them just hang around cafes and bars. They think we are pretty weird.’ When I get on the bike with them, I cannot tell if the people we pass by are amused or confused, but they do stare. Reyhan only learnt to ride a bike two years ago. ‘I was raised in a small village in Turkey and we did not have the money to buy a bike,’ she explains. On the way back, as I gaze through the window of the bus ride back to the central Taksim square, men dive and jump into the Bosphorus on this hot July day, as the hijabi-wearing women sit and look on. Whilst it is extra difficult to do sports if you are being raised traditionally - although Suzan seems as if she was more lucky - the headscarf could present an extra hurdle.

Dr Emma Tarlo, author of Visibly Muslim: Fashion, Politics, Faith, has produced research showing that women have been put off sport because of clothing. Cindy van den Bremen, who lives in the Netherlands and is married to a Turkish man, says that is just prejudice. She is the designer and founder of Capsters: sportive headscarves, based on a Velcro-technique; thanks to her design, Fifa lifted the hijab ban in cooperation with Prince Ali Bin Al-Hussein of Jordan. ‘What is important concerning sports and the hijab is the empowerment of women,’ she explains. ‘Women in islamic countries or communities have to face many thresholds to play and do sports. Role models in those regions are crucial for other women: they show them what’s possible, with or without the hijab. At Capsters, we are not for or against the headscarf, we just support the right to choice and free will. It’s up to her.’

A headscarf does not mean suppression per se, and a ‘modern’ outfit does not always equal a progressive mind. For some women, sports with a hijab is a way to get out of the ‘housewife sentence’ step by step, whilst for others it’s a deliberate and proud choice. Hijab or no hijab, it’s still battling to overcome traditional views on women’s roles in Turkish society. A fighter’s mentality surely comes in handy. In the video, athletics champion Nevin Yanit sums it up perfectly: ‘When girls start to do sports, many people ask if a woman do this.’ But after she won a gold medal at the European athletic championships in Barcelona, city officials from her town saw that she had worked on a dirt track, and decided to name a new athletics field in Mersin after her - and it's where she trains now.

This article is part of the fifth edition of cafebabel.com’s flagship project of 2012, the sequel to ‘Orient Express Reporter’, sending Balkan journalists to EU cities and vice versa for a mutual pendulum of insight. Many thanks to Burcu Baykurt, Cansu Ekemekcioglu, Recai Yuksel and the folks from MMA Corvos gym

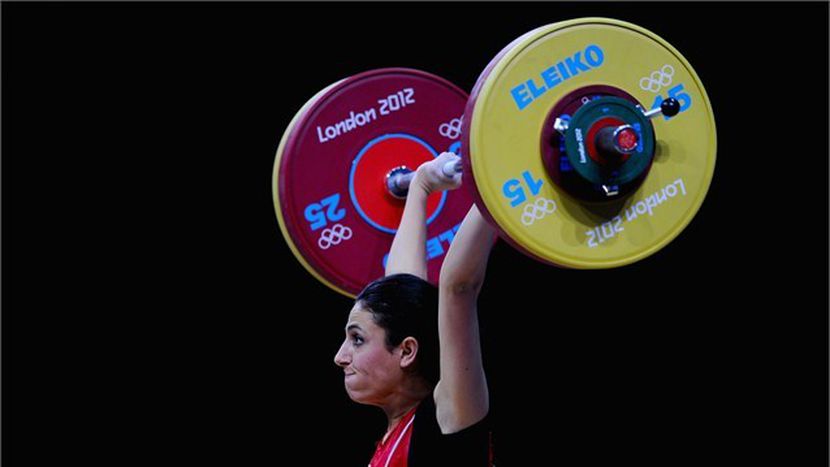

Images: main © courtesy of London Olympics 2012; in-text © Carole Viaene