Migrants keep coming to Seville, Spain and the rest of Europe

Published on

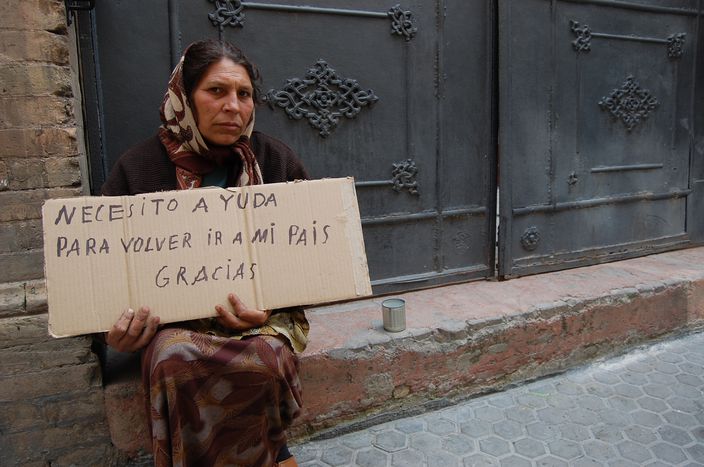

But their rights as workers and humans are at stake, while the status of illegal or legal are being sorted out

Around the corner from a barbers in the old centre of Seville, Madalin Escariu hangs out in the sun in front of the grocery shop where his friend works. ‘I came here two years ago because of my brother. He's married, has two kids and works here. I also want to marry a Spanish girl,’ he says, smiling. It was hard to find a job, and the 24-year-old now drives a lorry at night. He has a degree in industrial engineering, and had a good job in the former Yugoslavia, but wanted more than Romania. The transition to Seville was more or less smooth. ‘The paperwork was easy, because I am also from a country inside the European Union. I like it here. People treat me and other migrants well – not everywhere, but most people are nice.’

'The 2005 regularisation programme exacerbated the situation of migration in Spain'

Almost 600, 000 migrant workers turned 'legal' in the 2005-regularisation programme, implemented by the socialist government in Spain. It wasn't the first such programme, but it was the biggest of its kind: migrants who proved they could get a job were able to get their official work and residence permits in Spain. The mass programme met protest from some leaders in other EU countries and from the Spanish conservatives in the people's party (Partido Popular, PP). 'It was irresponsible to say that everyone had the right to come, because it was unrealistic,' says José Luis García, 27, president of the New Generations youth section of the PP in Seville. 'It exacerbated the situation of migration in Spain.’

Regulates to protect migrants

Kingsley, 26, walks in between cars waiting for the green light for twelve hours a day, one of the many Kleenex sellers at the city's traffic lights. At night he is Kingsley who misses his family and life in Nigeria, which he left three years ago. ‘I hoped that Europe was a better way to take responsibility of my family, but it wasn't as I thought. I'm just trying to survive. I travelled alone. I phone my family now and then. I didn't know that I had to have papers to work,’ he says. When he is lucky, he earns up to 15 euros (£13) per day selling handkerchiefs, but the income is uneven. ‘It would be better to have documents so I could get a job, but right now the government is not willing to help. I could have a regular income and plan how much money to send to my family.’

Kingsley, 26, walks in between cars waiting for the green light for twelve hours a day, one of the many Kleenex sellers at the city's traffic lights. At night he is Kingsley who misses his family and life in Nigeria, which he left three years ago. ‘I hoped that Europe was a better way to take responsibility of my family, but it wasn't as I thought. I'm just trying to survive. I travelled alone. I phone my family now and then. I didn't know that I had to have papers to work,’ he says. When he is lucky, he earns up to 15 euros (£13) per day selling handkerchiefs, but the income is uneven. ‘It would be better to have documents so I could get a job, but right now the government is not willing to help. I could have a regular income and plan how much money to send to my family.’

In the whole of Europe, the OECD has estimated that 5 - 8 million migrants work without documents. There are no precise statistics on undocumented migrants in Spain, but a recent report by the pan-European research project Undocumented Worker Transitions concluded that the mass regularisation did ‘not reduce the overall number of workers in the informal economy’. 'The programme was necessary because we cannot have migrants who live outside the law,' says Alejandro Jiménez García, 23, from the Spanish socialist party. 'Migrants will always come to Europe with or without regulations. They come here to have a better life, not to get papers,’ he says, adding migrants who work in the informal economy are more vulnerable than those who have documents.

Lida Fabiola Chiza Guangasi, 27, chops iceberg salad, tomatoes and onions in the Mezón El Serranito restaurant by the historic bullfighting arena in Seville. When she first came in 2000, she spent two years working for ‘100 euros (£88) and a pair of shoes’ before she ran away from her cousin who was mistreating her. ‘I was sleeping between two and three hours per night, working seven days a week. She was very strict. I'd go to buy oranges in the morning, then I'd clean the bathroom and the rest of the house. Her husband used to walk naked around insulting me,’ she recalls.

Lida Fabiola Chiza Guangasi, 27, chops iceberg salad, tomatoes and onions in the Mezón El Serranito restaurant by the historic bullfighting arena in Seville. When she first came in 2000, she spent two years working for ‘100 euros (£88) and a pair of shoes’ before she ran away from her cousin who was mistreating her. ‘I was sleeping between two and three hours per night, working seven days a week. She was very strict. I'd go to buy oranges in the morning, then I'd clean the bathroom and the rest of the house. Her husband used to walk naked around insulting me,’ she recalls.

When she fled from her cousin's slavery, she still did not have any papers allowing her to work in Spain, nor enough money to go back to Ecuador. She met her future husband and fell pregant, which in some ways was her ticket to a new future. ‘I had problems during the pregnancy and I had to go the doctor every fortnight, who decided to help me get the legal papers,’ she says, explaining what that act of humanity meant for her. ‘We are lucky that we met her. I am proud of her, she helped us.’ Other migrants might fear the system as such. Comisiones Obreas ('Worker Commisions'), one of Spain's two biggest trade unions, runs centres for migrant workers in the biggest cities and towns in Spain. They do not differentiate between migrant workers who do and don’t have documents. 'We protect the rights of all workers,' says Nora Barreiro, who works with the migration issue. ‘Migrants without papers might be more afraid to come to us if they have problems.’

Critique of EU efforts to fight illegal migration

In February 2009, the European parliament voted for the ‘sanctions directive’, targeting employers of illegal workers. ‘This law will send a strong signal to employers and to would-be illegal immigrants alike that Europe is not a free-for-all and that illegal employment is no longer tolerated,’ Simon Busuttil from Malta said before the vote. He is a member of the EPP-ED (group of the European people's party (christian democrats) and European democrats), the largest political group in the EU parliament.

'Tightening immigration controls push workers further into the shadows of the economy'

Both the conservatives and socialists voted for the directive. Alejandro Jiménez García from the latter sees the directive as a way of protecting the migrants rather than a signal that ‘Europe is not a free-for-all’. 'The migrants should be helped. They are in an illegal situation, but we cannot and we should not accept their superiors treating them differently to the legal workers,’ he says. Nevertheless, various migration rights groups and researchers criticise the new directive. ‘Tightening immigration controls do not eliminate undocumented work,’ experts behind the Undocumented Worker Transitions-project stated earlier this year, in a report also covering Spain; the new ‘sanctions directive’, together with other immigration laws on an EU level, might have the opposite results than their intentions. ‘Instead they push workers further into the shadows of the economy, working at nights, in private spaces, hidden from the communities which they secretly service doing the most difficult, arduous and sometimes dangerous jobs.’

Like Dadu, 28, who took a boat from Senegal to the Canary Islands, living in 'the colder' Madrid for a spell, before settling in Seville. 'You can't imagine what it's like for those who go by kayak,' he says about the experience. It is a spring Saturday at the Plaza de Pumarejo by the Maracarena arch, and he is enjoying a free meal at the Casa de la Pumarejo social centre, a kind of home for him, where he also gets Spanish classes for free. Two years ago he was spending his Saturdays with his family in Senegal. ‘I was as an electrician. I am the eldest of four. I came here by boat because it was difficult for me to support my family with the money I could earn in Senegal. Here it's another reality than I had imagined. Africa is very poor, but there we are free. In Europe there are limitations. The police are looking for you on every corner when you do not have papers and it is not like that in Senegal.' Dadu is currently unemployed, but he used to have a job in Seville. ‘I worked at a laundrette, but it closed for renovation. I do not have papers, and once they didn't pay me for three months.’ If he did not have to support his family he would have tried to go back. 'I am not here to think about myself. Since the moment I arrived I had to think about my family and earning money. I really want to have papers, so I can work more easily.’

Like Dadu, 28, who took a boat from Senegal to the Canary Islands, living in 'the colder' Madrid for a spell, before settling in Seville. 'You can't imagine what it's like for those who go by kayak,' he says about the experience. It is a spring Saturday at the Plaza de Pumarejo by the Maracarena arch, and he is enjoying a free meal at the Casa de la Pumarejo social centre, a kind of home for him, where he also gets Spanish classes for free. Two years ago he was spending his Saturdays with his family in Senegal. ‘I was as an electrician. I am the eldest of four. I came here by boat because it was difficult for me to support my family with the money I could earn in Senegal. Here it's another reality than I had imagined. Africa is very poor, but there we are free. In Europe there are limitations. The police are looking for you on every corner when you do not have papers and it is not like that in Senegal.' Dadu is currently unemployed, but he used to have a job in Seville. ‘I worked at a laundrette, but it closed for renovation. I do not have papers, and once they didn't pay me for three months.’ If he did not have to support his family he would have tried to go back. 'I am not here to think about myself. Since the moment I arrived I had to think about my family and earning money. I really want to have papers, so I can work more easily.’

Read more from our cafebabel.com local team in Seville