Michal Zygmunt: 'By 2010, Poland will be talking commercial gay movement'

Published on

Translation by:

Olia Yatskewich

Olia Yatskewich

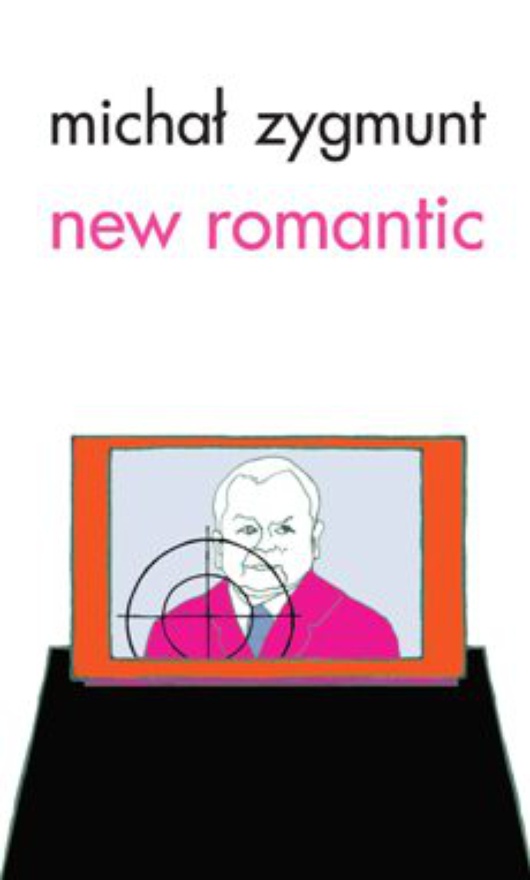

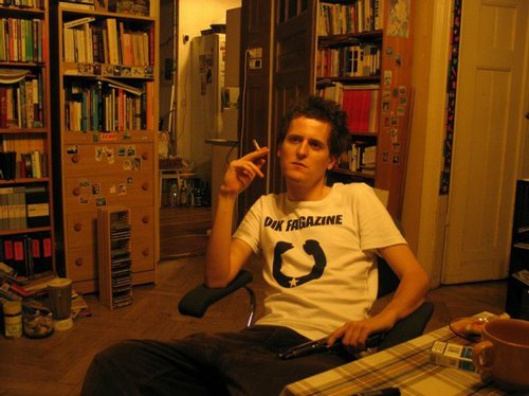

30-year-old author of the book ‘New Romantic’, the journalist and editor of gay magazine ‘Dik Fagazine’ talks politics, left-wing politics and emotion-drained religion

One day, Michal Zygmunt felt ‘strangled’ living in Wroclaw, southwestern Poland near the German border. A disintegrating long-term relationship and a few friendships led him to discover his wandering gene, which he believes he inherited from his Jewish grandfather. He moved to Warsaw where he published his first book - and enjoys life.

We meet in a restaurant in Mokotow, in the intellectual quarter of Warsaw, where Zygmunt lives, and loves as it reminds him of his dearest Wrocaw. He does not look like a revolutionary (and anyway, what does a revolutionary look like?). He talks intelligent and objective, yet always carrying a slightly ironic expression.

Political animal

‘Always’ interested in politics, Zygmunt conducted his first interview at the age of nine with Jerzy Urban, spokesman for the communist government. As a teenager, he was a member of different youth political organisations, starting with the far-right ‘Modzie Wszechpolska’ or the All Polish Youth. ‘I started with the far right. I even went camping with them, where a lot of strange, even homo-erotic events took place. However, what discouraged me was that for them, politics was just sitting on the sofa and talking.’ Now he finds himself in the left wing, but his outsider’s instinct keeps him different from the others. The Polish left wing has its greatest chances what with the shameful past of communism, and the problem of western politics lies somewhere else: ‘Today social democracy looks like the right wing, while the right wing looks like left wing.’ In his latest book New Romantic he expresses his fears: ‘This book is about post-politics, there are no more divisions, and this might lead to serious consequences. I refer with cause to the Red Fraction Army, which has come for voice when German political stage distribution disappeared. Unfortunately, history repeats itself.’

He’s also very critical of the European Union’s countries socialist governments’ involvement in big business: ‘Europe has many common problems. A lack of ideology leads to nationalism. It is not stressed enough that increment should not be the basis for actions, as dignity is the most important. The system of advanced payment is based on comradeship and has a lot of disadvantages. This is not yet so – for example, the supermarket chain Tesco does not pay enough, as it is a poor firm, but it stands for good wages.’

He’s also very critical of the European Union’s countries socialist governments’ involvement in big business: ‘Europe has many common problems. A lack of ideology leads to nationalism. It is not stressed enough that increment should not be the basis for actions, as dignity is the most important. The system of advanced payment is based on comradeship and has a lot of disadvantages. This is not yet so – for example, the supermarket chain Tesco does not pay enough, as it is a poor firm, but it stands for good wages.’

Declared leftwing, Zygmunt does not have illusions about strikes in western Europe: ‘It is obvious that these strikes are a result of people’s greed or interest in profit. Privileges should be given to certain people not to the whole professional group.’

Social sensitivity and disillusionment in politics pushed him to run for the president of Wrocaw in 2002. The committee campaign was called stars in the hair, and had a form of a happening showing absurd and nepotism of political life. ‘To get on the list of our party’s candidates, it was necessary to write a poem in my honour. We tended to show the relations between leaders and members of political parties. Also, I wanted to have an opportunity to participate in the debates with other candidates.’

’New Romantic’

There’s more on Polish political life in New Romantic - Zygmunt ‘kills’ leading Polish politicians including president Kaczyski and prime Minister Tusk, and he goes even further in showing Polish flaws and complexes. He also sneers at consumption, neo-romanticism and intellectuals: ‘I had a general idea: settlement of accounts with Polish myths where it counts victims from blood devoted.’

There’s more on Polish political life in New Romantic - Zygmunt ‘kills’ leading Polish politicians including president Kaczyski and prime Minister Tusk, and he goes even further in showing Polish flaws and complexes. He also sneers at consumption, neo-romanticism and intellectuals: ‘I had a general idea: settlement of accounts with Polish myths where it counts victims from blood devoted.’

At the same time he confesses that he cannot imagine living and writing anywhere else. ‘I can leave right now, but I do not want to – and it is clear to me that I want to live in Poland. I spent a year in Holland and Great Britain, but Poland is the best place. Also, things that I do not like, motivate me to work,’ he concludes with a smile, adding: ‘The level of emotion in Holland is annoying. Everything is so unusually calm that it makes you go crazy. This might be perfect for those who like to make some savings and enjoy clean streets, but most artists rather need ferment.’

His disillusionment with religion has had a strong influence on his work: ‘Years ago I attended church but the lack of emotions I felt helped me understand later that it was not for me. Religion is the worst propaganda strategy in politics. It appeals to dogmas and punishment and one cannot debate it. It is a form of manipulation – be it Islam in the east, or Catholicism here, but the system which relies on fear is a bad one.’

Europride today, commercial movement tomorrow

He may be editor of the gay magazine Dik Fagazine, but again, Zygmunt remains an outsider, choosing not to be a part of a mainstream gay movement: ‘We are interested in culture. We do not want to be in the union with activists.’ Dik is distributed widely, including in the United States and Japan. ‘We organise parties and exhibitions of the artists working with us. But also we are doing something that nobody else does, for instance we’ve published issues entirely focused on Romanian and Ukrainian specific themes.’

He may be editor of the gay magazine Dik Fagazine, but again, Zygmunt remains an outsider, choosing not to be a part of a mainstream gay movement: ‘We are interested in culture. We do not want to be in the union with activists.’ Dik is distributed widely, including in the United States and Japan. ‘We organise parties and exhibitions of the artists working with us. But also we are doing something that nobody else does, for instance we’ve published issues entirely focused on Romanian and Ukrainian specific themes.’

He is pretty calm about the future of the gay movement, maybe because he has always been surrounded by intellectuals and has never experienced acts of aggression: ‘This is a habit effect – we know we’ll be organizing gay Europride 2010 which attracts almost a million people. I think that starting from 2010 we will already be talking about the commercialisation of the movement in Poland.’

In effect, Zygmunt takes a sober view of himself and his work: ‘Journalism is fascinating and gives me the possibility to earn money. Writing satisfies my metaphysical needs. I have a lot of ideas for a new book, but I realise, that I would be a buffoon calling myself a writer after publishing only one book. I was really tired of this book by the time I thought what I’d written was relatively weak. I even wanted to call it back from printing but it was too late.’ A good thing; New Romantic was well received by its critics and public.

In-text photos: (www.michalzygmunt.pl)

Translated from Michał Zygmunt: Artystów kręci ferment