Michael Johansson: Stripping Objects of Function through Installation Art

Published on

Doesn't every object have a history, a story to which an endless stream of associations is bound? Swedish installation artist Michael Johannsson surely thinks so. His artwork tantalises its viewers to experience a conglomerated fictional reality of associations and memories in a three-dimensional, sculptural form.

Michael Johansson grew up in Trollhättan, a town of roughly 50,000 inhabitants nestled not too far away from the Swedish west-coast. From a very young age he had a deep interest in drawing, but his expectations of how art should look constricted him. He wanted his drawings to look realistic, to come as close as possible to visual fidelity. That turned out to be a challenge later on when he attended art school. But now, his artwork, which relies on real, tangible objects, seems to not only embody the desire from his youth for realism, but also produces an entirely different, and admittedly unreal context through which to view those objects.

Breaking Free of the Mould

When Johansson was 19 years old, he attended a prepatory school for the arts before attending a series of universities and discovering his style. "I experimented with different techniques and media, such as sculpture and photography." But Johansson was conservative with art, and could not overcome the hurdles that went along with what we in the writing profession call "finding our voice." It wasn't until after he had begun working on his Master's degree at the Malmö Art Academy in Sweden when he began to bloom into the artist that he is known as today. "If I had been confronted with the art I do today, when I was starting out, I do not think I  would have liked it very much. I think it would have been difficult for me to even appreciate it as art." Toward the end of his postgraduate education, Johansson had already participated in a few exhibitions, but when it came to his final project, he wanted to do something different. That is when he really became immersed in what he does today, creating pieces from various common, household objects that communicate to the viewer something about our relationship as humans to objects. But in order to do this, Johansson had to break the mould he had created for himself. "I wanted to try something new for my Master's project while I still had the chance to do so in the safety net of the university. The only thing I regret about my education is that I did not take more risks." Taking those risks turned out to be very fruitful, and from looking at the result, the viewer gets the sense that taking risks should really be at the center of any artist's process.

would have liked it very much. I think it would have been difficult for me to even appreciate it as art." Toward the end of his postgraduate education, Johansson had already participated in a few exhibitions, but when it came to his final project, he wanted to do something different. That is when he really became immersed in what he does today, creating pieces from various common, household objects that communicate to the viewer something about our relationship as humans to objects. But in order to do this, Johansson had to break the mould he had created for himself. "I wanted to try something new for my Master's project while I still had the chance to do so in the safety net of the university. The only thing I regret about my education is that I did not take more risks." Taking those risks turned out to be very fruitful, and from looking at the result, the viewer gets the sense that taking risks should really be at the center of any artist's process.

New Functions, Unsual Compositions

Through his final exhibition, Johansson found something that he felt he could relate to and build on; by piecing together used, everday household objects, Johansson strips them of their standard functions and contexts and gives them new ones. "If a sculpture consists of a hundred different items, they come from a hundred different homes, and were used by hundreds of different people. But now they're combined into one sculpture, one installation piece. In other words, lives are formed into one fake identity that never existed." Johansson's piece The Move Overseas is a good example. The piece was made for an exhibition in Belgium, which required a lot of planning in its execution to overcome technical and structural difficulties. "The idea initially was to create an invisible container through which you could see, to give a glimpse into objects that were manufactured overseas before being shipped somewhere else." But Johansson also holds the clear view that his interpretation of the piece is not necessarily the only or right one. He does not, in other words, think his view is more important than the viewer's, because the viewers are the ones that carry the associations with the objects that are put on display. "Of course, I do not want people to claim that I mean something that I do not, but if it is a private interpretation, it is fine."

Through his final exhibition, Johansson found something that he felt he could relate to and build on; by piecing together used, everday household objects, Johansson strips them of their standard functions and contexts and gives them new ones. "If a sculpture consists of a hundred different items, they come from a hundred different homes, and were used by hundreds of different people. But now they're combined into one sculpture, one installation piece. In other words, lives are formed into one fake identity that never existed." Johansson's piece The Move Overseas is a good example. The piece was made for an exhibition in Belgium, which required a lot of planning in its execution to overcome technical and structural difficulties. "The idea initially was to create an invisible container through which you could see, to give a glimpse into objects that were manufactured overseas before being shipped somewhere else." But Johansson also holds the clear view that his interpretation of the piece is not necessarily the only or right one. He does not, in other words, think his view is more important than the viewer's, because the viewers are the ones that carry the associations with the objects that are put on display. "Of course, I do not want people to claim that I mean something that I do not, but if it is a private interpretation, it is fine."

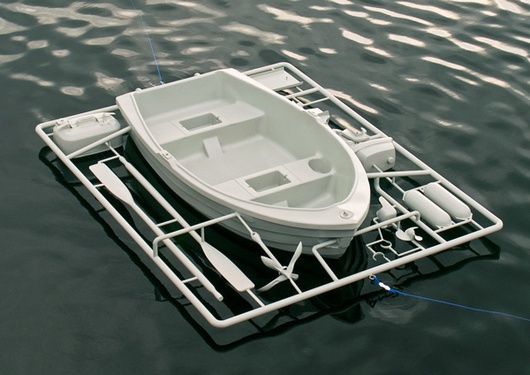

Reversing the Production Line

Another approach to Johansson's artwork has been to take objects back to a point of origin. The representations of those origin bring back vivid memories to anyone who grew up as a child piecing together model kits of cars, boats, trains, planes, tanks and whatever else model toy companies think children enjoy shrinking down to managable sizes. But Johansson's pieces are different. Rather than creating minature versions of objects, he has gone with a different approach. "The year after I worked on my Master's I had a residency in Stockholm. I was going to a meeting by train and was flipping through some old sketchbooks from seven years earlier." That's when he rediscovered an idea he had at the beginning of his studies: to make model kits in 1:1 scale. "Of course, I had no idea back then how to produce it. The budget was very limited, so I realised on the train that if I used the real items and transfomed them into model kits, I could cut down on the cost." That is how pieces like Manual Lawn Mower Assembly Kit (2011) and Assorted Garden Assembly (2010) emerged. "I wanted to take away the function from the objects and do an almost reverse building process. Here it was important for me to maintain the same aspect of stripping objects of their functions and meanings like in my other works."

Another approach to Johansson's artwork has been to take objects back to a point of origin. The representations of those origin bring back vivid memories to anyone who grew up as a child piecing together model kits of cars, boats, trains, planes, tanks and whatever else model toy companies think children enjoy shrinking down to managable sizes. But Johansson's pieces are different. Rather than creating minature versions of objects, he has gone with a different approach. "The year after I worked on my Master's I had a residency in Stockholm. I was going to a meeting by train and was flipping through some old sketchbooks from seven years earlier." That's when he rediscovered an idea he had at the beginning of his studies: to make model kits in 1:1 scale. "Of course, I had no idea back then how to produce it. The budget was very limited, so I realised on the train that if I used the real items and transfomed them into model kits, I could cut down on the cost." That is how pieces like Manual Lawn Mower Assembly Kit (2011) and Assorted Garden Assembly (2010) emerged. "I wanted to take away the function from the objects and do an almost reverse building process. Here it was important for me to maintain the same aspect of stripping objects of their functions and meanings like in my other works."

There is one model kit piece, however, for which Johansson modelled the parts to be used off of the real objects instead, before having them cast in bronze. Hard Hat Diving (2011) was created for a naval base on the Swedish east coast that specialises in diving and underwater tactics. And because it was intended as a permanent, outdoor installation, it had to be weather resistant. "The navy let me borrow all the materials and rubber suits, and I then had this amazing bronze casting studio in Malmö cast the parts in bronze."

There is one model kit piece, however, for which Johansson modelled the parts to be used off of the real objects instead, before having them cast in bronze. Hard Hat Diving (2011) was created for a naval base on the Swedish east coast that specialises in diving and underwater tactics. And because it was intended as a permanent, outdoor installation, it had to be weather resistant. "The navy let me borrow all the materials and rubber suits, and I then had this amazing bronze casting studio in Malmö cast the parts in bronze."

Again, all of these model kit pieces aim at reversing the production lines of objects, to see their various parts compartmentalised and separated, much like when a novice mechanic takes apart an engine to get a better understanding of how it functions. Do the objects in these pieces seem more sterile and materialistic than they would in their complete form? Does being stripped of a function make an object meaningless, or does it only enhance its existence? Whether looking at his model kit pieces or his pieces where household objects are put together in three-dimensional cubes, the viewer can't help but ask her or himself philosophical questions like these, questions that cut straight to the heart of our relationship as humans with objects.

If you'd like to see more of Michael Johansson's work, check out his website!