Metro-run university of Paris 14 challenges French ‘anti-egalitarian’ education system

Published on

The newly formed university is a mobilisation of students, teachers and researchers who aim to liberate education from the over-arching confines of the ‘institution’. Participants Emile Gayoso and Quentin Lade on neo-liberalism, the Bologna process and giving classes on public transport

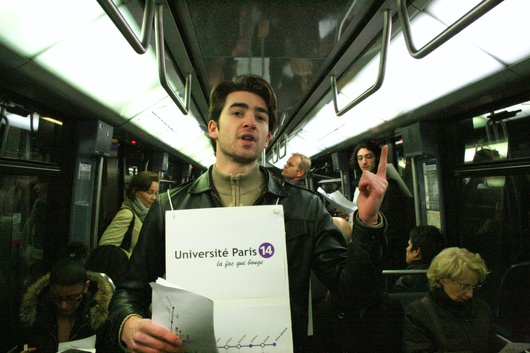

It’s 2pm on Wednesday afternoon, and Paris’s metro line 14 is filling up with commuters. Most of them are going to and from the landmark Bibliothèque Francois Mitterand - a bastion of France’s educational system. Here on the train however, an education of a different kind is unfolding. Several men and women in sandwich boards bearing the logo ‘Université de Paris 14’ are distributing leaflets to the passengers. Class, it would seem, is in session. ‘We meet at the BNF,’ explains Emile Gayoso, 24, ‘and make the return journey to Gare Saint Lazare, encouraging discussion and distributing information. The listeners are usually more or less interested, rarely annoyed, and often totally on our side.’

‘Breaking through the inner circle of French education’

Fighting against successive reforms that have transformed the average European university from a social nucleus of learning into a money-hungry ‘excellence’ machine, Paris 14 is a nomadic entity that celebrates the joy of learning and the exchange of knowledge. It was the brainchild of students and teachers at Université de Paris 7, but welcomes participation from all corners of society. Impromptu ‘Flash courses‘ (each specially adapted to the average metro commute at 15-20 minutes long) bring intellectual discussion back into the real world. ‘At Paris 14 anyone can follow to course,’ says Gayoso, ‘from professionals in the area, to students or anyone else outside the university system who wants to use this public platform to share their ideas.’ Subjects are diverse; ancient mythology, contemporary politics or the writings of Roland Barthes are equally likely to be put to the (albeit moving) floor. Despite the challenges of getting people to publicly engage with something decidedly unfamiliar, Gayoso looks with pride on the fact that he has helped open a new avenue of discussion amongst ordinary people. ‘We have demonstrated that the problems in the university system don’t only concern those in the ‘inner circle’ of French education,’ he says, ‘but everyone in society.’

‘Falling in step with a neo-liberal ideology’

It was the recent educational strikes, claims Quentin Lade, 23, that initially brought ‘Paris 14’ together. However, their small group soon began to wonder whether the university system as they knew it was something they wanted to defend. ‘The strikes are necessary to prevent the university becoming subordinate to financial enterprise,’ he explains. ‘But the movements lack scope and political ambition.’ In his opinion, the hierarchical structure of French education, with the elite ‘Grande Ecoles’ sitting atop the pyramid, is inegalitarian in its very principle. ‘The children of the elite have every chance to go to the same Grandes Ecoles as their parents, while those of the working classes have less and less opportunity to avail of superiour education.’ This aspect of French education has only been accentuated, he says, with recent decisions taken by the EU. ‘Universities are in the process of falling in step with a neo-liberal ideology that would see them transformed into profit-making machines. These reforms place the individual, the researcher and the university itself into competition with economic theory. Inequality is an assumed element of a system that privileges arbitrary ‘excellence’. This is an absurd and dangerous vision, where brute force is the only law.’

It was the recent educational strikes, claims Quentin Lade, 23, that initially brought ‘Paris 14’ together. However, their small group soon began to wonder whether the university system as they knew it was something they wanted to defend. ‘The strikes are necessary to prevent the university becoming subordinate to financial enterprise,’ he explains. ‘But the movements lack scope and political ambition.’ In his opinion, the hierarchical structure of French education, with the elite ‘Grande Ecoles’ sitting atop the pyramid, is inegalitarian in its very principle. ‘The children of the elite have every chance to go to the same Grandes Ecoles as their parents, while those of the working classes have less and less opportunity to avail of superiour education.’ This aspect of French education has only been accentuated, he says, with recent decisions taken by the EU. ‘Universities are in the process of falling in step with a neo-liberal ideology that would see them transformed into profit-making machines. These reforms place the individual, the researcher and the university itself into competition with economic theory. Inequality is an assumed element of a system that privileges arbitrary ‘excellence’. This is an absurd and dangerous vision, where brute force is the only law.’

‘Collectively renounce the democratic ideal’

The controversial Bologna process is, according to Lade, the expression of neo-liberal ideology at a European level. ‘It is a project we must fight against with resilience if we don’t want to see the European university assume the role of procuring wealth,’ he says. So, with Bologna hypothetically on the chopping block, what is Paris 14’s vision of an ideal education system? ‘University, school - should it not be a space where students, everyone, has the means to make choices, both individual and collective? Where one can come together with their fellow citizens to question what constitutes the order of things, and try to improve them - without cease?,’ asks Lade. ‘That is to say render the democratic ideal possible - something that we have, evidently, collectively renounced.’ Indeed, as hundreds of commuters alight metro line 14 to face the imposing edifice of the Bibliotheque National, perhaps their recent ‘flash course‘ with Paris 14 will give them a fresh perspective on what education is really all about, and what it has lost.