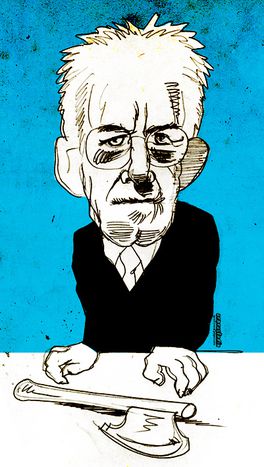

Meeting Mario Monti, interim Italian prime minister

Published on

On 13 November the independent candidate, known as the president of Italian university Bocconi, officially succeeded Silvio Berlusconi in the middle of a deep debt crisis. Ave Mario, cries French newspaper Le Monde. Super Mario, scream spoof websites. We meet at a press conference in Berlin

When boarding his flight from Milan to Berlin on the morning of 9 November, fellow passengers asked Mario Monti if he was really taking a flight in the right direction. ‘I checked, of course,’ the 68-year-old replied. Monti’s anecdote is for the audience at the Dahrendorf Symposium at the Berlin academy of sciences and humanities, a British-German event which is being held between 9 and 10 November 2011. Everyone laughs with Monti, who is an economist and former European union commissioner.

No Monti python

Success follows suit. After prime minister Silvio Berlusconi’s announcement to ‘gradually step back’ in November, the name of ‘Mario Monti’ figured prominently in media speculations on who could follow as Italian prime minister designate. Signs were already pointing in his direction. On the first day of the symposium in Berlin, Monti was appointed a lifetime senator by the Italian president, Giorgio Napolitano, though officially both issues are not linked.

Born in 1943 in the Lombard town of Varese, in northern Italy, Monti studied economics in Italy and the United States. He subsequently became professor of economics at the universities of Milan, Turin and Trento. Unlike most of his European academic colleagues, Monti is a 'Brussels man'. From 1995 to 1999 he served as internal market commissioner at the European commission (which controls the supervision of the EU market for financial services - ed) before becoming commissioner for competition until 2004.

Reminding us of what Italy actually is

Back in Berlin, Monti is part of a panel concentrating on the financial and euro crisis. He judges the euro to be a success story, although concerns remain: ‘The euro was meant to bring together European countries, but it is dividing them,’ he says, stating the obvious. ‘Stereotypes are coming back, pitting north against south.’ Monti’s advice is that Italy needs a more active European policy. ‘We are by no means a peripheral country. Italy can’t evade its responsibility of being a founding nation.’ A more active role of Italy in European politics could also benefit the European union. ‘The function of the Franco-German couple would have been better if Italy wouldn’t have completely expelled itself from this couple in the last past years.’

'Italy can’t evade its responsibility of being a founding nation'

To save the common currency, a new approach has to be taken in Italy, but also in Germany, Monti says. ‘I would like to see a Germany that will be even stronger, more rigorous, less short-term-oriented and more patient.’ Italy should consolidate and maintenance its public finances, as it needs both more growth and fewer deficits. ‘There is no much intellectual divergence on this matter,’ Monti admits. To achieve more growth and lower deficits, he calls for a cutback of structural impediments in the Italian economic system. ‘Growth needs structural reforms,’ he said. To achieve this, why not have an Italian-style grand coalition of major political parties? Monti will have the chance to implement this sooner than he thinks.

Read the original post on cafebabel.com Berlin's blog

Images: main (cc) aeneastudio/ Flickr/ aeneastudio.blogspot.com