Matonge district: heart of darkness

Published on

Translation by:

Francesca ReinhardtMarked by the imposing office high-rises of the European Union, the institutional centre of Brussels symbolises the power of European civilisation. Beside it, the African quarter of Matongé follows life in a completely different rhythm

In Brussels this June, yet another European summit is kicking off. The sun reflects off the flawless windowpanes of the European parliament. Journalists line up neatly in a row, waiting to go through the scanner and identify themselves at the entrance. Then a laser checks the contents of bags and briefcases. Order and perfect transparency. Europe’s bureaucratic dream.

Dialogue in fashion

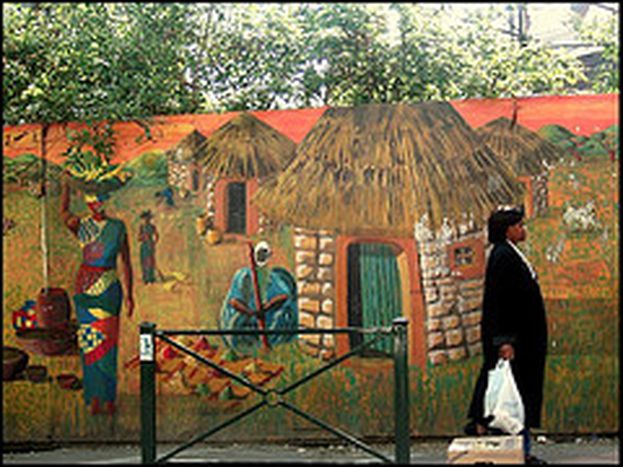

Meanwhile, only 500m away in the Matongé neighbourhood, the annual festival is under preparations. I make my way there in the hope that I can take part in this festival of culture, which, every year at the end of June, transforms this part of the city into an African village. Or so I read in an online forum. Just 500m from the centre of Brussels, at the entrance to the triangle of streets Chaussée d'Ixelles, Chaussée de Wavre and rue de la Paix, I am greeted with a sign reading Matongé en Couleurs (‘Colourful Matongé’).

Meanwhile, only 500m away in the Matongé neighbourhood, the annual festival is under preparations. I make my way there in the hope that I can take part in this festival of culture, which, every year at the end of June, transforms this part of the city into an African village. Or so I read in an online forum. Just 500m from the centre of Brussels, at the entrance to the triangle of streets Chaussée d'Ixelles, Chaussée de Wavre and rue de la Paix, I am greeted with a sign reading Matongé en Couleurs (‘Colourful Matongé’).

I imagine the neighbourhood to be full of businesses with products reading ‘made in Africa’, being for many years the arrival point for African emigrants, particularly from the Congo. I expect real African specialties, real African cuisine, and real African music. On the day of the biggest festival in the neighbourhood, I hope to participate, along with other indigenous Europeans, in a multicultural world, transcending borders and creating dialogue between different tastes and cultures.

Around 10am, the first vendors start to set up their wares. There are bags and shoes, imitating well-known and exclusive brand names, plastic toys and stuffed animals ‘made in China’, colourful Pakistani scarves, brightly coloured woven goods from India, and all kinds of plastic fashion accessories. By midday, hundreds of people are wandering around the stands, run mainly by Asian immigrants.

The smell of freshly cut onions and grilled sausages hangs in the air and disco music drones from loudspeakers on the vendors’ stands. The only African flavour comes from a Congolese woman with a child, selling traditional folk crafts. Her stand is on the outskirts of the attractions, and does not enjoy any special attention. ‘I haven’t been able to sell anything yet,’ she says.

Aggressive rap music and Brazilian dance

In the afternoon, I speak with a very promising actor and vocalist from the jazz band The Peas Project. Kambisi Zinga-Botao, like many other emigrants from the Democratic Republic of Congo, arrived in Brussels in the nineties. He has not sought out an apartment in Matongé for himself. ‘I hardly ever come here, these days,’ he says, although he cannot or does not want to explain why. There is something sad in his eyes when he reflects on it. He smiles, though, at the thought of his countrymen, sitting out on the street on plastic chairs in the summer. ‘Someone who doesn’t understand the culture might be upset at them blocking the street. But that is totally Africa. There, time is not a constraint.’ ‘So can you remain African and at the same time feel at home in Brussels?’ I ask. Kambisi wraps himself in a meaningful silence, and I take this question back with me to Matongé.

In the evening, the festival becomes increasingly black. Aggressive rap lyrics are to be heard from the stage and almost no whites are in the audience. There is no common celebration and no cultural exchange. The white Europeans are no longer to be seen among the stands. ‘People are afraid to walk around there at night,’ says Swietlana, who has lived in Belgium for a few years. A group of young people are dancing to Brazilian music beside a MacDonalds. I ask myself what the expression ‘real African culture’ means today. In Matongé, I cannot find the answer.

The next day, I make my way to the Flemish town of Tervuren, which is fifteen minutes away and home to the Royal Museum of Central Africa. I want to learn what has happened to this culture.

‘Some cultures must in some ways die’

The Royal Museum of Central Africa has a special exhibition this year. Exactly fifty years ago, when the Congo was still a Belgian colony, Brussels organised the World Expo, which was specially devoted to the Belgian Congo. It was the anniversary of the annexation of the Congo, and the king wanted to use the exhibition to justify further control over the colony. The second world war had sealed the end of Europe’s mastery over the world, and independence movements were springing up in the colonies.

The Royal Museum of Central Africa has a special exhibition this year. Exactly fifty years ago, when the Congo was still a Belgian colony, Brussels organised the World Expo, which was specially devoted to the Belgian Congo. It was the anniversary of the annexation of the Congo, and the king wanted to use the exhibition to justify further control over the colony. The second world war had sealed the end of Europe’s mastery over the world, and independence movements were springing up in the colonies.

The Belgian strategy was to invite indigenous Congolese to Belgium, where they were presented as an emancipated people – but not to the extent that the protecting hand of Belgium was no longer necessary. Today, the museum still boasts the ghostly exotic animals with expressionless eyes, like a monument to King Leopold II. Even now, he has kept the reputation of a great ruler and civiliser. ‘Perhaps it does annoy us a bit,’ say some Congolese, living in Belgium. Belgians whom I asked were of the view that it was a part of history that should not be forgotten. Both sides were surprised by this question.

The 1948 Colonial Fair in Brussels was also surprising, both for Belgians as well as for Congolese. The former got to see smiling, educated, well-dressed slaves. The Congolese, for their part, were astonished and overwhelmed by the warm welcome they received. They also got to see Belgians, their erstwhile masters, doing menial jobs, such as preparing meals and making beds.

It would appear that the effective chasm between the two nations from fifty years ago has not yet been overcome. ‘What is the difference between the cultures?’ I ask the deputy mayor of Brussels, Bertina Mampak. ‘Which cultures?’ he replies. ‘My wife is Belgian. We dress ourselves from the same shops and eat hamburgers together at MacDonalds. I don’t have a problem with it. There are many people who work things out this way. Whenever there is some kind of integration problem, we are often ourselves to blame. Black people must believe in themselves. They must be open to whites and have white friends. They have to work twice as hard and project success. When they run businesses, then they must open punctually at eight. Some cultures must in some ways die.’

Translated from Czarne serce Brukseli