Mass tourism in Mallorca: Trouble in paradise

Published on

Mallorca is not all about sea, sun and sex. The island’s population, which makes up less than 1 million residents, is starting to feel the weight of the 2 million tourists that arrive each summer. Locals have had enough of rent prices rising and public spaces disappearing. During a protest last month they finally faced the music and said what had to be said: “it has come to this.”

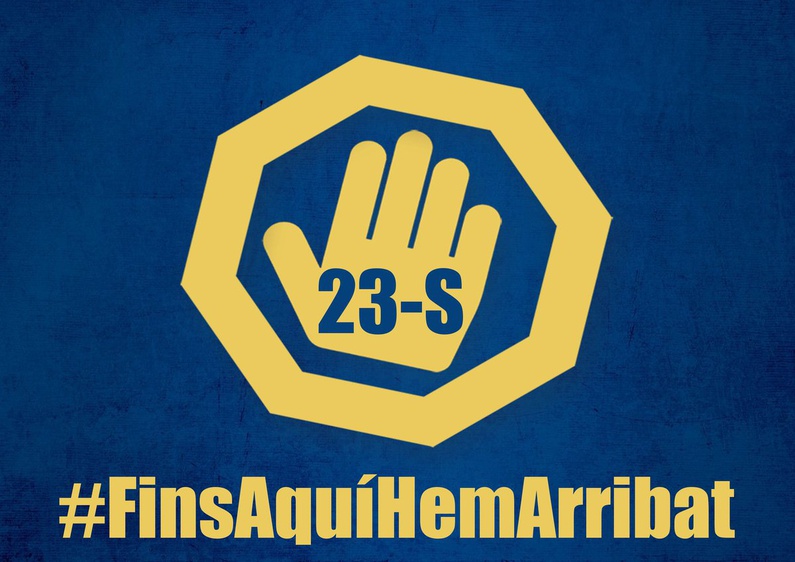

As the tourism industry in Mallorca continues to grow with yet another record-breaking summer of arrivals, locals are taking to the streets to voice their concerns. On Saturday the 23rd of September, a demonstration was organised by several activist groups under the banner “Fins aquí hem arribat”, which loosely translates to “it has come to this”. Locals are trying everything to raise awareness of the negative consequences of unregulated tourism and to send a message to the local government. This counter-movement has been growing over the last few years, with organisations tirelessly trying to counter mass tourism.

The reasons for protest are endless: the environmental impact on beaches and green spaces, air and noise pollution, gentrification of urban neighbourhoods, overcrowding, unavailability of long-term rental apartments, precarious working conditions for locals and the destruction of the traditional economic model and way of life. And Mallorca is no exception; the same kinds of protests busied the streets of Barcelona and other popular tourist cities in Europe over the last few years. The protest signs read: “Without limits, there is no future”. While it can seem strange to those who have always believed tourism only brings benefits through economic gains for the region, the reality of this relentless influx of holidaymakers, low-cost airlines and cheap accommodation options is clearly not what the locals had in mind.

When tourists double an island’s population

For Northern Europeans, Mallorca has always been seen as a sun-kissed holiday destination, a perfect escape from dreary London weather and the daily grind in Paris (metro, boulot, dodo). Tourism was first encouraged towards the end of the 19th Century, when local businessmen and politicians wanted to show off the island’s beauty and culture to the wider world.

By 1973, the new airport was welcoming over 7 million passengers annually. This enormous influx provoked radical changes in the socio-economic structure of the island, bringing unprecedented levels of immigration from the peninsula and changing the geographical distribution of the population and the economic activity on the island.

Today, certain areas of the island have become known as party destinations. Almost a rite of passage for many Brits and Germans, booze-fuelled trips to the island have become commonplace amongst young people looking for sun, sea and sex. Resorts like Magaluf and the Arenal have successfully managed to rebrand themselves and, while families and honeymooners used to spend their summer getaways there, they now welcome 18-30 year old revellers throughout an increasing long high season.

If that doesn’t illustrate the gravity of the situation, these numbers surely will... The last few summers have seen a surge in the numbers of visitors to the island. Over 13 million passengers arrived by plane to Mallorca in 2016, up from around 11 million in 2015. Mallorca has a population of less than 1 million and almost 2 million passengers arrive by plane per month over the summer months. This means that the amount of people on the island roughly doubles over these months, not including arrivals by boat.

The strain on infrastructure is something that often goes unnoticed by travellers but has a very real impact on permanent residents. Medical professionals complain of overcrowding in hospitals during the summer months, and the confusion of adding foreign languages to the mix complicates an already difficult situation.

Goodbye cheap housing, goodbye public spaces

According to a recent study published in a local newspaper, Diario de Mallorca, whilst the national average inflation in the housing market has been approximately 1.25% so far in 2017, Palma has experienced a rise of 7.2%. This has made renting increasingly difficult for young professionals and students. Many young Majorcans continue to live with their parents well into their thirties.

Walking around the city centre of Palma, it is hard to miss the yellow and black of Ciutat per qui l’habita posters stuck to windows and hanging from balconies. Originating from a collection of residents’ organisations, they have made it their mission to stand up for the wellbeing of local residents. Ciutat per qui l’habita raises awareness on mass tourism and sends strong messages to authorities that something must be done. One of their goals is to draw attention to the insane amounts of uninhabited properties in Palma. Because of digital platforms like AirBnB, many urban properties have been bought for the sole purpose of short-term holiday rentals.

Marc Morell, a member of Ciutat per qui l’habita and an academic at the Universitat de Les Illes Balears who has closely studied the gentrification process in Palma, believes that the main issue is the rent gap. “The rent gap comes from the difference between what tenants can pay and what landlords feel they can now charge… whilst what people are prepared and able to pay has steadily increased, the amount landlords can charge has skyrocketed.” He holds one arm almost flat on the table at an angle of about 10 degrees to indicate the amount tenants can pay and then place his other arm above it at an angle of around 45 degrees: “Over time, the difference has been growing and growing.” Marc argues that gentrification, in the case of Palma, “is not about the new arrivals. The so called middle-classes who enter these neighbourhoods change the profile of the residents, but it is the owners of the properties and the popularity of holiday rental apartments that lead to the unaffordable rise in rents.” Whilst in other cities gentrification is the result of an affluent middle-class arriving in cheap neighbourhoods, Marc argues that Palma’s case is linked to holiday rental apartments.

Marc Morell, a member of Ciutat per qui l’habita and an academic at the Universitat de Les Illes Balears who has closely studied the gentrification process in Palma, believes that the main issue is the rent gap. “The rent gap comes from the difference between what tenants can pay and what landlords feel they can now charge… whilst what people are prepared and able to pay has steadily increased, the amount landlords can charge has skyrocketed.” He holds one arm almost flat on the table at an angle of about 10 degrees to indicate the amount tenants can pay and then place his other arm above it at an angle of around 45 degrees: “Over time, the difference has been growing and growing.” Marc argues that gentrification, in the case of Palma, “is not about the new arrivals. The so called middle-classes who enter these neighbourhoods change the profile of the residents, but it is the owners of the properties and the popularity of holiday rental apartments that lead to the unaffordable rise in rents.” Whilst in other cities gentrification is the result of an affluent middle-class arriving in cheap neighbourhoods, Marc argues that Palma’s case is linked to holiday rental apartments.

Ciutat per qui l’habita also fights for a right to public spaces, which have been taken over by terraces from restaurants and hotels. Marc explains how they recently organised an event where a large group of people gathered to eat together in a public square. It wasn’t a cosy dinner. The local police attempted to move them and threatened them with heavy fines, claiming they were “disrupting the free movement of pedestrians.”

“Businesses can rent out these spaces for advertising campaigns and yet people cannot gather to eat together in a supposedly public space… the new law prevents us from being a population who can freely criticise.” Marc is referring to the controversial “Ley Mordaza”, which regulates protests (including peaceful sit-ins) and prohibits those that haven't been given permission.

Feliciano is feliç

Not all Majorcans agree with Marc. Feliciano, the owner of the small bar called Merendero Minyones near the highly touristic Passeig del Born, explains how even jobs that seem unrelated to tourism have benefited from the boost in economic activity in the city. He revealed that, although very few of his customers are actually tourists, his daily customers are made up of an eclectic mix of construction workers, high street vendors, mechanics, tour operators and waiters and waitresses whose livelihoods depend on tourism. “This city depends on tourism. None of us would have jobs without it. It is impossible to talk about Mallorca without tourism.” Feliciano was also quick to point out the increasingly cosmopolitan make up of his neighbourhood: “Where once there was a very narrow cultural and social profile of residents in his area, I now have neighbours of all nationalities, races, sexual orientations and ages.” Feliciano sees the increased diversity in his neighbourhood as the positive footprint that tourism has left upon his city.

However, what people often forget when supporting the economic gains argument is to ask who really benefits from these economic gains. It’s evident that mass tourism in Mallorca generates enormous sums of money, but are these riches felt by the majority of the island’s population?

“It has come to this”

An organisation that has been attempting to debunk the popular myth that tourism equals economic prosperity is Front comú en defensa del territori. At a fundraising event for a documentary they hope to release in 2018, one of their members explained the origins and objectives of their movement: “We wanted to show people the real effects of tourism on people who live in Mallorca. We are always told how beneficial tourism is to our economy but the reality that we experience is different. It is true that we now depend on tourism but is this relationship really healthy and sustainable? We have banked it all on the tourism model but what happens if the bubble bursts? What happens if there is a boom in petrol prices and the cost of travel goes up? We urgently need to establish a healthier relationship with tourism. Over the last few years, the numbers have risen and risen. We are at world record levels and the island is at saturation point.”

During the protest on the 23rd of September, testimonies from evicted tenants and underpaid hotel workers were read out amid vocal boos and cheers from the crowds. Suddenly it was clear to see that the supposed benefits from mass tourism clashed violently with the reality experienced by locals. Organisers spoke of reclaiming lost elements of Majorcan life that were stolen by an economy overly dependent on tourism. The protest took place on the Passeig del Born, where Feliciano’s bar is located, home to luxury designer retailers and upmarket eateries. The Passeig dissects the centre of Palma, and comes to an end alongside the Royal Gardens and the Cathedral – both extremely popular locations for tourists. The surrounding neighbourhoods neatly demonstrate the kind of gentrification Ciutat per qui l’habita want to avoid.

Angels Isern and Llucia Juan, both 30, attended the demonstration and explained their reasons for doing so. Angels and Llucia expressed their frustration at the rising rent prices in Palma and the difficulty they and their friends have had in trying to find accommodation. “It is now almost impossible to find an apartment in Palma for less than 800 Euros a month. A few years ago it would have been so much easier because tourists stayed in hotels and resorts, and visited the city for a day or two,” said Angels. Llucia explained how the model change was something locals had originally encouraged: “We wanted visitors to get to know the island. I always told them: ‘you should rent a car and explore the island. Don’t just stay in the resort by the pool.’ We wanted them to integrate into the local culture and interact with local people. But now, with AirBnB and the motorways crammed full of rental cars, I’m not sure it has been a positive change.”

Angels Isern and Llucia Juan, both 30, attended the demonstration and explained their reasons for doing so. Angels and Llucia expressed their frustration at the rising rent prices in Palma and the difficulty they and their friends have had in trying to find accommodation. “It is now almost impossible to find an apartment in Palma for less than 800 Euros a month. A few years ago it would have been so much easier because tourists stayed in hotels and resorts, and visited the city for a day or two,” said Angels. Llucia explained how the model change was something locals had originally encouraged: “We wanted visitors to get to know the island. I always told them: ‘you should rent a car and explore the island. Don’t just stay in the resort by the pool.’ We wanted them to integrate into the local culture and interact with local people. But now, with AirBnB and the motorways crammed full of rental cars, I’m not sure it has been a positive change.”

“We used to have secret beaches where we could go, and we knew it wouldn't be full of tourists,” a saddened Angels explains. “But now, thanks to the Internet, it’s easy for tourists to rent a car and search for the nicest hidden beaches and coves. Historical sites in the mountains and picturesque towns we have always gone to are now full of tourists and prices have gone up everywhere.”

Tourism has helped make Mallorca one of the richest regions in Spain, but it’s clear to see that young people are finding it more and more difficult to enter the housing market and find stable employment. Digital platforms and tourists’ desire for an authentic experience have had a significant impact on the island’s residents. Rising rent prices and crowded public spaces means that Majorcans constantly come into contact with tourists and the aftershocks of mass tourism. But today, residents are facing the music by saying enough is enough, “it has come to this”.