Marzena Sowa: 'in communist Poland I'd dream about getting a Barbie from Pewex'

Published on

Translation by:

olia yatskewich

olia yatskewich

At 28, the author of comic series 'Marzi' – about a little girl living in the Polish People’s Republic - on her own story as a Pole between France and Belgium

It's a frosty, windy winter morning at the popular Café Belga on Flagey Square in Brussels. As I approach, I keep an eye out for a woman who might be freezing and checking her diary, apprehensive of being late for her next scheduled meeting. Before I see her, a young, tall woman with big blue eyes sees me. It's hard not to recognise the cheerful and charismatic Marzena Sowa.

I am Marzi

Marzena Sowa and partner Sylvain Savoia, 39, met long before they co-wrote Marzi. It was Savoia who encouraged the recent Michel de Montaigne University literature graduate in Bordeaux to put her memories on paper. 'I'd tell Sylvain a lot of stories about living in communist Poland,' says Sowa, who left Poland after finishing romance language studies at the Jagiellon University in Krakow.

'He'd listen incredulously, visualising it, even taking notes. One day he asked me what I would do when I told my grandchildren about my childhood; if, by that time, my memories would fade away. I started writing a diary; Marzi is me.'

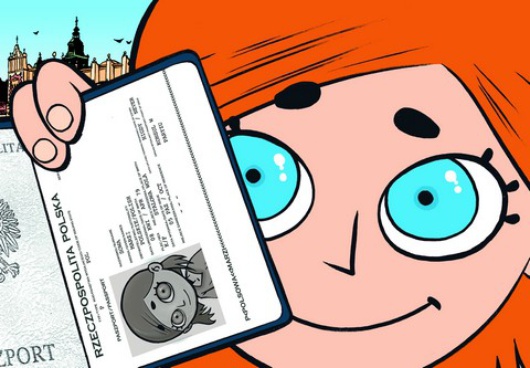

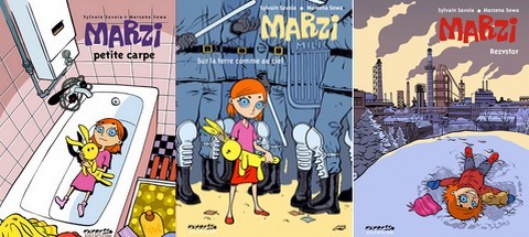

Marzi with her Polish passport and below, Sowa's three books published so far: 'Petit carp' (2005), 'Sur la terre comme au ciel' (2006), 'Rezystor' (2007), all by Dupuis (Images: Sylvain Savoia)

Marzi with her Polish passport and below, Sowa's three books published so far: 'Petit carp' (2005), 'Sur la terre comme au ciel' (2006), 'Rezystor' (2007), all by Dupuis (Images: Sylvain Savoia)

Sowa's position as an outsider in Bordeaux allowed her to have a distant take on Polish reality and her childhood. 'When you live outside your own country, it is easier to write about things that 'made you',' says the Stalowa Wola-born cartoonist. 'Distance allows you to look objectively on the past. It is easier to write about memories that already 'nest in your head'.'

Sowa's position as an outsider in Bordeaux allowed her to have a distant take on Polish reality and her childhood. 'When you live outside your own country, it is easier to write about things that 'made you',' says the Stalowa Wola-born cartoonist. 'Distance allows you to look objectively on the past. It is easier to write about memories that already 'nest in your head'.'

While Marzi is a completely autobiographical book, it is also a testimony of the Poland's severe communist times; the live carp which was kept in the bath before Christmas day, queues at the butchers, Teleranek or even children’s interest in the announcement of the martial law. And what about 'the rest of the world'? Social and culture barriers can make it more difficult for foreigners to understand Sowa's book, and who usually learn about Poland in the eighties mainly through newspapers and television.

Polish life was normal, too

'Sometimes readers find it surprising that besides strikes, usually associated with Jaruzelski and 'Solidarity', people also had a regular life,' the author explains. 'I mean, going to school and to work, children playing in the courtyards, holidays. My comics won’t age. Even twenty years on you will find something new, something for yourself. We were all children, and we all had some wishes that never came true; I was always dreaming about getting Barbie from Pewex (communist-time stores which sold Western goods in exchange for Western currencies).'

While a little girl, playing with dolls, was Marzena Sowa already dreaming about being a writer? 'I wanted to be a translator, represent a 'word', but yes, I did dream about writing,' she confesses. 'From quite early on I wrote poems, stories as an introvert observer. I tended, like Truman Capote at the beginning of his career, to depict the world around me, not myself, as it looked more passionate. I was always fascinated by photography. I love taking pictures. The moment when you develop them is unforgettable. In Marzi I do not evaluate history; I do not try to teach people, I try to share my views on the world, to show how I remember it. It reminds me of taking pictures.'

Click slideshow to see pics of Marzi - and read one page of the comic (French)

Brussels charms vs Poland

At the moment Marzena and Sylvain are working on the next instalment in Marzi’s rites of passage, namely her years at school and departure to study in France. Watch this space though. 'I like the idea of writing a comic about the Warsaw uprising. People in other countries know so little about this event. I want to focus on the experience of ordinary people, maintain a little distance from historical facts. I was thinking of adapting Polish author Maria Krüger's children's story, Karolcia (1959). Comics are widespread in Europe. I see it as an ideal form of illustration.'

Marzena does not intend to go back to Poland. Brussels fascinates her with its international perspective and co-existence of different cultures. 'Even if it is raining the whole time - I'm joking,' she laughs, 'at the same time you can stay anonymous. Although, my country is the place where I can always return,' she says, her blue eyes sparkling.

'I feel more Polish in France and Belgium than in Poland,' she finishes, as she glances at freezing passers-by. 'After all, in order to write and draw, it is enough to just go on the street; history is here and now.'

Marzi reads herself in 3D

Translated from Marzena Sowa: Marzi to ja!