Mario Monicelli: 'commedia all’italiana encompassed everything from love to death'

Published on

Translation by:

Mary MaistrelloThe 93-year-old Italian director and father of the ‘commedia all’Italiana’ film genre, on the power of cinema which ‘acts like a mirror, tells a story, but doesn’t preach’.

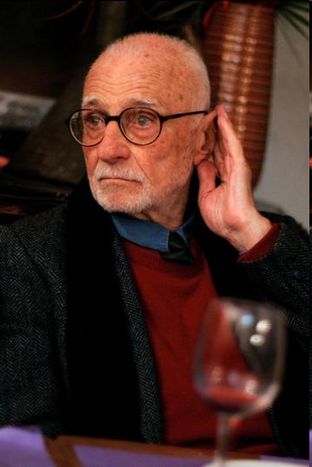

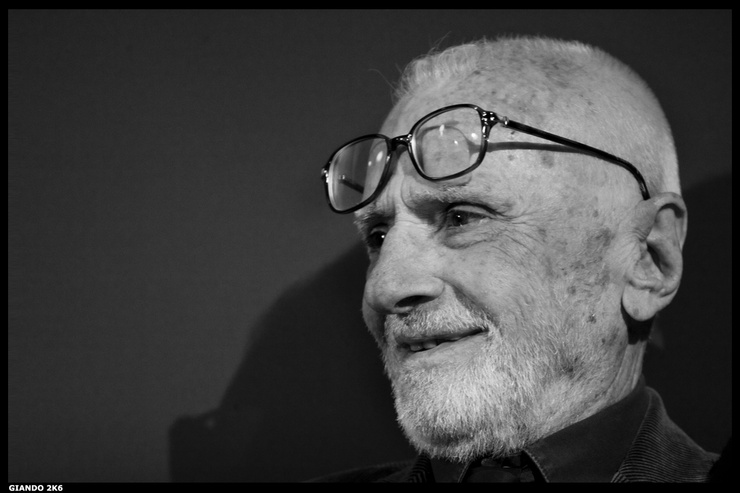

He's as bleary-eyed as a surgeon on a 48-hour shift, enveloped in monastic silence and wearing a cap. This is Mario Monicelli, a cinema legend as well as the father of ‘commedia all’Italiana’. ‘Italian comedy-style’ is a completely Italian film genre, characterised by levity but at the same time by satire and critique, and it peaked between the fifties and sixties. I walk beside him silently, waiting to sit down and to find out what the future holds for ‘his’ comedy, and where cinema itself is heading. He walks slowly, curved but proud under the weight of  ninety-three years, more than sixty of which are marked by an illustrious prize-winning career in cinematography. To be precise, that's over sixty-five years if you count his screenplays, directing, feature films, theatre and especially comedies. He has worked with all the greats, including Marcello Mastroianni, Alberto Sordi, Totò, Vittorio Gassmann, French actor Gérard Depardieu and even Pierpaolo Pasolini. He’s been fêted in Paris where he is presenting a book called L'espressione triste che fa ridere. Totò e Monicelli (‘The Sad Countenance Which Makes One Laugh’) by Adriana Settuario. He is also giving a cinema lecture ‘Monicelli by Monicelli’ at the Cinémathèque Française venue, which is showcasing a two month retrospective in his honour on the 110th anniversary of the birth of famous actor Totò. We direct ourselves to a brasserie and roll camera, we’re on.

ninety-three years, more than sixty of which are marked by an illustrious prize-winning career in cinematography. To be precise, that's over sixty-five years if you count his screenplays, directing, feature films, theatre and especially comedies. He has worked with all the greats, including Marcello Mastroianni, Alberto Sordi, Totò, Vittorio Gassmann, French actor Gérard Depardieu and even Pierpaolo Pasolini. He’s been fêted in Paris where he is presenting a book called L'espressione triste che fa ridere. Totò e Monicelli (‘The Sad Countenance Which Makes One Laugh’) by Adriana Settuario. He is also giving a cinema lecture ‘Monicelli by Monicelli’ at the Cinémathèque Française venue, which is showcasing a two month retrospective in his honour on the 110th anniversary of the birth of famous actor Totò. We direct ourselves to a brasserie and roll camera, we’re on.

Monicelli's commedia all'italiana

‘The commedia all'italiana is comedy which does not solely deal with customs,’ exhorts Monicelli, replying to the deliberation that ‘his’ comedy – a satire on bourgeois settings with characters defined by strong Italian traits, the best of these being Totò – has had equably remarkable success outside of Italy. ‘It is a light exchange between the characters, and it hinges on life and current events. Therefore the more regional it is, the more it becomes international, because it relies on universal factors. It starts with the musical score.’ And of course, who could forget the scores by Nino Rota from Armata Brancaleone (‘For Love And Gold’, 1966), or the one from I Soliti Ignoti (‘Big Deal on Madonna Street’, 1958)?

‘The commedia all'italiana is comedy which does not solely deal with customs,’ exhorts Monicelli, replying to the deliberation that ‘his’ comedy – a satire on bourgeois settings with characters defined by strong Italian traits, the best of these being Totò – has had equably remarkable success outside of Italy. ‘It is a light exchange between the characters, and it hinges on life and current events. Therefore the more regional it is, the more it becomes international, because it relies on universal factors. It starts with the musical score.’ And of course, who could forget the scores by Nino Rota from Armata Brancaleone (‘For Love And Gold’, 1966), or the one from I Soliti Ignoti (‘Big Deal on Madonna Street’, 1958)?

In the meantime, his Earl Grey tea and my café noisette have arrived. They both sound so un-Italian to us that we begin to discuss what makes Italy and France so similar. ‘Whenever Italians do something, they do it in a very Italian way, but they try to make sure that everyone is happy,’ he replies solemnly. One cannot help asking the father of I Soliti Ignoti where the commedia all'italiana comes from. ‘It comes from way back,' he replies, 'from the commedia dell'arte, from the characters created by sixteenth century Italian writer and actor Ruzante and Machiavelli, to quote but two. One has to underline the fact that it’s called ‘comedy’ and not ‘tragedy’. It encompassed everything from love to death, passing through hunger, poverty, sickness and violence. It generates a desperation that nevertheless fills you with hope through laughter.’

Cinema evolving with European society

As for the commedia all’italiana today: what can be said of Italian colleague Carlo Verdone, who many see as the heir to this type of comedy? ‘He’s a good director and a good actor but he has no courage. He only does comedy ‘not in the Italian style’. His work is characterised by cute films, even if they're well-made, but where superficial things happen where things turn out well. Always. The commedia all'italiana is the opposite: nothing is resolved and you’re left with a bittersweet feeling,’ he glosses. He puts his glasses down on his cap next to the teapot, and it starts to snow outside. Who have been the most interesting amongst the actors, screenwriters and directors with whom Monicelli has worked? ‘I have always worked with the best people, who always had something to say and who thought along the same lines as me,' he says. 'So I always felt at ease with them, and they with me, as we shared the same thoughts on life and survival.’

As for the commedia all’italiana today: what can be said of Italian colleague Carlo Verdone, who many see as the heir to this type of comedy? ‘He’s a good director and a good actor but he has no courage. He only does comedy ‘not in the Italian style’. His work is characterised by cute films, even if they're well-made, but where superficial things happen where things turn out well. Always. The commedia all'italiana is the opposite: nothing is resolved and you’re left with a bittersweet feeling,’ he glosses. He puts his glasses down on his cap next to the teapot, and it starts to snow outside. Who have been the most interesting amongst the actors, screenwriters and directors with whom Monicelli has worked? ‘I have always worked with the best people, who always had something to say and who thought along the same lines as me,' he says. 'So I always felt at ease with them, and they with me, as we shared the same thoughts on life and survival.’

Because Monicelli has made history as well as witnessed it, I take my cue to try to understand how he sees the future, cinema and Europe. ‘Cinema evolves in line with society: if the latter evolves, so does cinema. One mirrors the other. The problem is that the west is in a phase of decline, as I always show in my films,’ he says sadly. And what is the cause of this decline? ‘It’s the law of the market; the strongest wins and gains most.’ So here he is, the Monicelli who brought up twentieth century Italians on characters filled with bitterness, cynicism and scepticism.

Is cinema powerful? ‘It has the power to mirror, to tell a story, but not the power to preach,’ he replies. So does it narrate without acting on matters? ‘Perhaps, with the result that a spectator, Italian or not, might want to find out more for himself.’ It's a cynical lesson in 'Monicelli-realism', which preserves neither intolerance, friends nor family, the worst of enemies, as presented in his 1992 movie Parenti Serpenti.

What does he think of this Europe which is continually expanding to the east? ‘The economy is winning. That’s why France is interested in Romania, for example,’ he replies with dry bitterness. Will this expansion balance out the American superpower? ‘No, no. Neither Europe nor the whole of the west put together.’ On American cinema, Monicelli says 'it’s definitely not one with great characters.’

'We need to change; don’t put too much trust in democracy'

So which directors stand out on the European horizon? ‘There’s one Italian, Gianni Amelio. I’m thinking of the film Il ladro di bambini (The Stolen Children’, 1992). And a few others.’ Should cinema touch your heart? ‘The mind, rather.’ As I take my leave, I ask him for a recipe for Europe; what can be done? ‘We need to change; don’t put too much trust in democracy. My advice is comedy - European-style.’

This interview was first published on cafebabel.com in 2005. It has been republished in respect of Monicelli's passing on 29 November 2010 in Rome, aged 95

Translated from Mario Monicelli: «Una ricetta per l'Europa? La commedia europea»