Maria Di Stefano: I capture the cultural contradiction in capitalism

Published on

Translation by:

Gabriel ButtigiegBorn in Abruzzo, brought up in Rome, and with a degree in art-history obtained at Sorbonne in Paris, Maria Di Stefano is a multimedia artist who from 4th to 6th of October 2019, exhibited two of his unpublished works—Rouge and World Hello, at the Digitalive Romaeuropa Festival 2019. We interviewed him about the contradiction of contemporary capitalism, as well as Trump, and the role of artists today.

Maria, what was your first contact with art?

I have a memory which may seem trivial—a school trip to the National Museum of Capodimonte, in Naples. We visited the Flagellation of Christ by Caravaggio. I had an effect on me that I had never experienced before. I remember thinking, “Wow, that rocks.”

If you had to explain in a few words who a multimedia artist is, how would you put it?

Let's say that a multimedia artist is not just a painter, a video maker, or anything else, but in fact, is characterised by the use of multiple formats within the same work.

What is multimedia in your art?

To create sensory stimulation on multiple levels. Thanks to sound and film, I have elements to create the most complete, truthful and realistic story. For example, sound is the strongest proof that an artist has been in a certain place. That said, in my opinion, the visual component remains the pivot of multimedia production.

How did you become a multimedia artist?

After high school, I studied Art History with a specialisation in cinema and photography at the Sorbonne in Paris. So, I come from a more theoretical-critical route, rather than a technical one. After studying in Paris, I went to an arts school in the UK. And after that, I gained work experience in the United States, in New York and Los Angeles. I wanted to stay in the USA, but then came the Trump cyclone...

And then?

And then I started having administrative problems, starting with visas: One bureaucratic difficulty after another. Before long, I didn't feel safe anymore and decided to return to Italy.

You found Salvini at home though...

If you want to put it that way (laughs). Jokes aside, I came back and found some fantastic people here in Rome who I work with today. I was able to put into practice what I wanted. In reality, I kept moving a lot but Paris remains an important city. Then I went to Berlin and I started developing this documentary-like format, thanks to which I always find a good opportunity to go somewhere else.

Were World Hello e Rouge, which you presented here at the Digitalive Romaeuropa Festival, created from these trips?

Yes, they were created in 2018, while working in Berlin. More precisely, during my stay in the German Capital I discovered the Asian commercial and cultural centre, the Dong Xuan Centre — which became the focus of World Hello. But during the months I spent in Germany, I also had the opportunity to go for a month to the Amazon—this is where Rouge was created.

However, from a conceptual point of view, what gave birth to World Hello e Rouge?

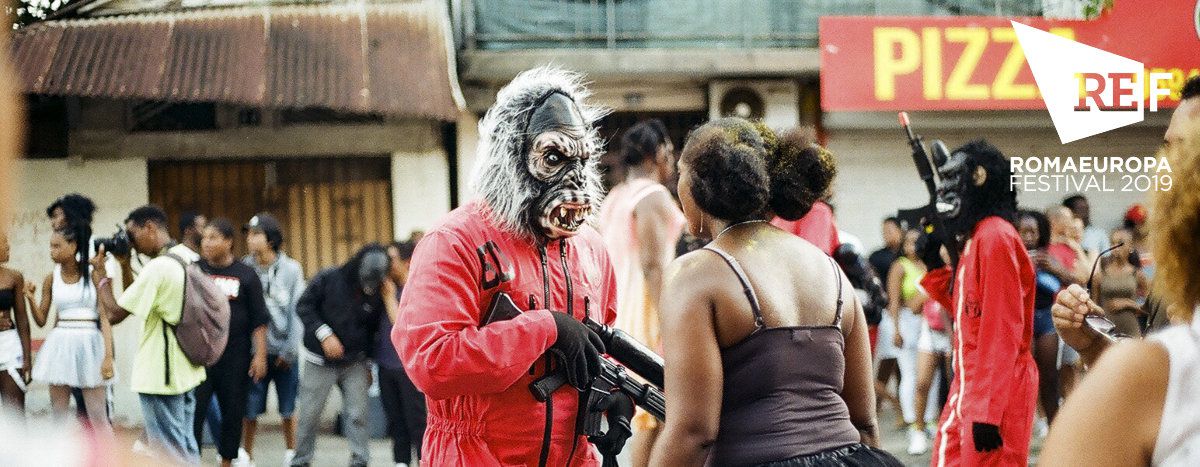

The idea stems from the similarities I observed in the two places—in the Dong Xuan Centre, in Berlin, and in the area between Cayenne and Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni, in French Guyana. These are obviously two different cultural microcosms, but united by being inserted into another context. In the case of Cayenne and Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni I tried to "capture" the everyday life of the indigenous population and the relationship between the latter and the new cultures developed in the area over time. In the film, I try to show how this relationship oscillates between an intersection, on one hand, and an almost sectarian separation on the other. I noticed the same contradiction in Berlin. The Dong Xuan Centre is an enormous space, made up of numbered sheds, each one a different mini-Asia. Inside, you find a little bit of everything: cultural association, but also retail and wholesale stores.

When I saw World Hello and Rouge, the word-sensations that came to mind were the following: Anxiety, suffocation, faith, schizophrenia, breath and nostalgia and nostalgia. Why?

Because I am interested in capturing the contradictions, I would say above all the cultural appropriation of contemporary capitalism and the loss of sacredness, the purity that it entails. This is especially seen in Rouge. As soon as you leave the home of the natives, you reach the Cayenne Carnival, an event made of music, violence, alcohol, the police, etc. It's as if the first place was a sacred place, suspended in a world of chaos. Moreover, contemporaneity is the looming of too many stimuli. And as for the word “schizophrenia” I believe it is also fueled by the continuous overlap of the online and the offline.

In a sense, you capture this contemporary schizophrenia, but you don't refuse it...

I don't think it's refusable.

In the two works, there are some vertical panoramas that tend to focus on some seemingly irrelevant details like crumbling windows, spirit-catching objects…

Let's say that in the upward movement there's a narrative. While in the moment which I stop on a detail, it totally changes the point of view and creates disorientation, all from a particular rhythm to the film.

Among the various formats that you use, there's analogue photography. Do you refuse to use digital?

After learning to photograph digitally, today I prefer to use analogue. But, more generally, technique isn't something fundamental to me. I could replace one camera with another. There's no fetishism in that sense. Multimedia matters a lot more. In the work I present here at the Digitalive Romaeuropa Festival, there are analogue photos that I made with a 90s handycam and audio recordings made with an iPhone.

What is your relationship with art?

I still see art as something utopian. I find it hard to say with conviction: Yes, I am an artist but that is partly because I feel guilty, and partly because I feel like I'm pulling it off.

In what sense?

Making art is a privilege because we are fortunate to deal with something that is fundamentally useless, but this uselessness is the most beautiful thing in art itself. If I didn't present these photos at the Digitalive Romaeuropa Festival 2019, nothing special would happen. Artists do not save lives. But I like to think that we are busy with making life more enjoyable or interesting and to focus the attention on something that goes beyond people's basic needs.

I'll just say that this is all the influence of the French critical spirit…

Don't get me wrong, I'm very happy to be here and to be able to exhibit my works, but I don't presume to change the world.

But, from what you say, art definitely seems to have a social role The byline of your website reads “My art will not help the hunger but will satisfy a carving”...

Literally it means “Art can't end hunger, but it can satsify an appetite.” In other words, yes, art definitely has a social role, but I am not interested in doing surveys, or giving socio-politcal judgements. I simply try to document ordinary stories in an artistic way. To follow these figures in everyday life—often it's a daily life that's faraway from here, in Italy. From the specification, I try to touch on broader issues. Art can't be totally abstract, otherwise it becomes a sort of manifestation of one's ego in a tangible dimension.

Would you describe yourself as an idealist?

(Hesitates), I think so.

How do you measure the success of your work?

I rely on people's curiosity and reaction. When someone watches the work from start to finish and comes and asks me questions about the various "why's" behind the installation, I feel satisfied.

Translated from Maria Di Stefano: «Catturo le contraddizioni culturali del capitalismo»