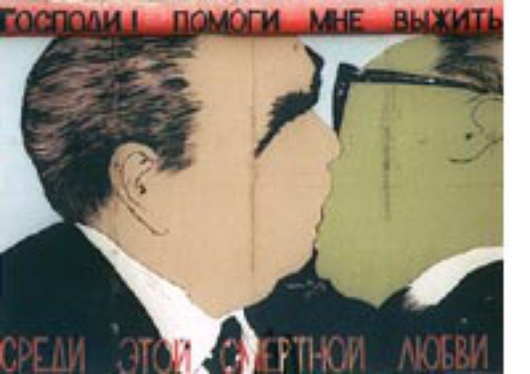

Love through the Iron Curtain

Published on

Translation by:

lindsey evans

lindsey evans

When it comes to love, there’s no denying the appeal of the exotic: while Western men were fascinated by the ‘Eastern girl’, in the Eastern bloc Westerners were equated not only with the myth of the Latin Lover or the decent, well-off West German, but were also constantly seen as a possible springboard into freedom.

Even the borders of a divided Europe couldn’t stand in the way of love. In the Communist era, dual nationality couples were not rare. On the contrary, ‘Eastern girls’ were very popular in the West for being unusual, quick and eager to learn, modest and thrifty. Young Czech, Slovakian and Polish women soon discovered their chance to get through the Iron Curtain. Hundreds married their way into Germany, Holland and Austria in order to flee the East. About 300 women left the former Czechoslovakia in this way each year, accounting for 0.3% of a total 90,000 marriages. Transnational marriage was a simple means of getting a Western passport and thereby becoming a citizen of a free state. Men had it a lot harder, since their movements were followed more closely by the state. 90% of marriage applications made by men of a working age, who could contribute to the country’s productivity, were declined by the authorities. Elderly citizens, on the other hand, were mostly allowed to marry through the Wall, since their leaving relieved the state of its obligations to care for them in old age, particularly where funding their pensions was concerned.

Even the borders of a divided Europe couldn’t stand in the way of love. In the Communist era, dual nationality couples were not rare. On the contrary, ‘Eastern girls’ were very popular in the West for being unusual, quick and eager to learn, modest and thrifty. Young Czech, Slovakian and Polish women soon discovered their chance to get through the Iron Curtain. Hundreds married their way into Germany, Holland and Austria in order to flee the East. About 300 women left the former Czechoslovakia in this way each year, accounting for 0.3% of a total 90,000 marriages. Transnational marriage was a simple means of getting a Western passport and thereby becoming a citizen of a free state. Men had it a lot harder, since their movements were followed more closely by the state. 90% of marriage applications made by men of a working age, who could contribute to the country’s productivity, were declined by the authorities. Elderly citizens, on the other hand, were mostly allowed to marry through the Wall, since their leaving relieved the state of its obligations to care for them in old age, particularly where funding their pensions was concerned.

‘Escape marriages’ à la Rosa Luxemburg

It goes without saying that it wasn’t always true love. Over 100 years ago, ‘Mrs Gustav Lübeck’, better known by her maiden name Rosa Luxemburg, had already identified the advantages of a Western marriage; the politician of Russian nationality married a Prussian in 1898. This marriage of convenience earned her a German passport and protected her from deportation back to Tsarist Russia.

To many would-be ex-pats of the Communist era, especially women, marriage to a Westerner often seemed like their only chance to leave the country ‘legally’ and, above all, with the prospect of being allowed back in again. The ‘Helsinki Accords’ of 1975 formed the basis for these mixed marriages; its terms were intended to create a kind of controlled cooperation between the Eastern and Western blocs in Europe. Staged ‘escape marriages’ often involved a lot of money: Daniela, a nurse from East Berlin, met Peter G. – a West German – in 1987 and offered him 25,000 Marks to marry her. In order not to arouse the suspicions of the GDR authorities, a show of fake love was planned with military precision. In 1989, just a few months before the fall of the Wall, the plan finally worked – Daniela was able to travel into the West.

New era, new relationships

After the collapse of the Communist system in 1989, many couples returned to the East to start a new life. Experience of working in the West meant that people could start up profitable and fast-growing businesses. Thus, love also contributed to the growth of Central and Eastern European infrastructure. But many East-West relationships were shattered as a result of this urge to go back home. Eastern women had gained in self-confidence and no longer wanted to be viewed as ‘fitters-in’. Those who are still in love but didn’t want to resettle together for economic reasons are leading long-distance relationships. According to a dual nationality couple living in Prague, these families base themselves near airports and try to make up for lost time by going on holidays, spending weekends together, and bringing up their children bilingual.

Thanks to the enlargement of the EU, the political element of East-West relationships has today faded into the background. Now, more and more mixed couples - Italians with Czech girlfriends, French women going out with Poles, German boys falling for Latvians - are lovingly whispering to each other: Miluji te, ti amo, je t’aime, kocham cie, ich liebe dich, es tavi milu, or simply, in Europe’s lingua franca, I love you…

Translated from Die Liebe über den Eisernen Vorhang