London: Hackney Wick, Fish Island and the shadow of cool

Published on

Translation by:

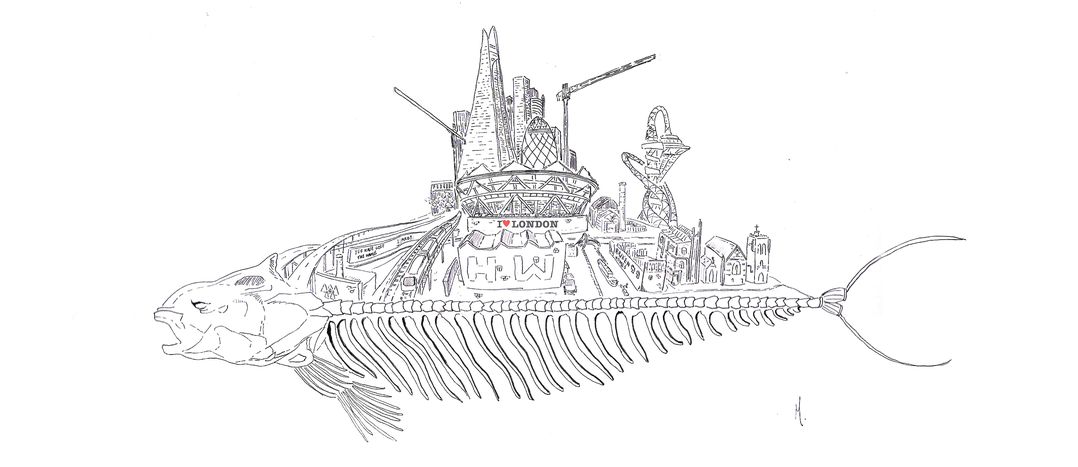

Monica BibersonIn 2012, the Olympic Games were hosted across the river from the London districts of Hackney Wick and Fish Island, home to the largest concentration of artists' studios in Europe. The bunting is now down and the athletes gone to sprint elsewhere; but for the locals threatened with exclusion, the muscle ache will endure much longer than expected.

As the train doors open onto a wet platform one stop before Stratford, you instantly see the transformation that London's East End has been subject to these past few years. In the foreground, two huge red letters – H and W – cover the front of a former factory. They stand for the initials of a district that was once a jewel of the British economy.

Further back, behind a labyrinth of ancient streets catapulted into the modern age by resident artists, you catch sight of the River Lea canal that separates Hackney Wick from its twin, Fish Island. The latter – more discreet, less flashy and spared the curious tourists and pub-crawlers of the former – is full of similar treasures: Victorian factory works and gigantic warehouses, even the oldest salmon smokery in London. Everything has been partially or completely converted into shared working and living spaces, or studios for social, art, and cultural activities.

Finally, looking like another planet on a collision course to smash into these older districts, the Olympic Stadium and the ArcelorMittal Orbit Tower blend in with the dull grey weather. They are the remnants of the 2012 London Olympic Games.

Bringing colour to the walls and pavements

In reality, the red graffiti was cut out from a mural commissioned by the Coca-Cola company (an official sponsor of the Games), which used to cover the whole wall until outraged locals scrawled the word "shame" across it.

In reality, the red graffiti was cut out from a mural commissioned by the Coca-Cola company (an official sponsor of the Games), which used to cover the whole wall until outraged locals scrawled the word "shame" across it.

Today, there is no trace left of this message (it is virtually impossible to find an image of the vandalised wall except here), a controversy that would be quite banal if it did not symbolise a much more important problem – one that confronts the inhabitants of Hackney Wick and Fish Island (from now on referred to as HWFI). It is a textbook case of gentrification and the abuse of power. All this in a city that has one of the highest levels of socio-economic inequality in Europe.

Traditional industry formed the heart of local activity here until it's collapse in the 1980s. It is within these factory walls that the first artificial plastic material, Parkesine, was invented. After this decline, hectares of space inside buildings were left unoccupied, then turned into squats and, eventually, housing – often for artists who were feeling the pinch.

In this state of creative atmosphere of self-sufficiency, a new generation of HWFI inhabitants laid the foundation for a parallel socio-economic system based on the principles of mutual aid, spontaneity and free experimentation. For years, such a movement brought colour to walls and pavements under the relatively indifferent gaze of the capital's public authorities. Until, that is, it was announced that the Olympic Games were on their way. Then the promise of a quick profit caused the City to start to salivate.

The R word is the new G word

As recently as a decade ago, you could hear being said that if you knew the meaning of the word "gentrification" then you were doubtless taking part in it. Initially an academic term (coined by the London researcher Ruth Glass in 1964), this word is now very commonly used, most often in an accusatory way.

The G word has thus gradually been banned from the property developers' vocabulary, being replaced by terms with a much more positive connotation such as "regeneration". The latter has nevertheless been identified as a symptom of the same phenomenon in Staying Put: An Anti-Gentrification Handbook for Council Estates in London.

In it, we find two questions under the header "[gentrification] Signs to look out for on your estate": "Has your local council listed your estate as a potential development site?" and "Does your estate sit within a London Plan ‘Opportunity Area’?"

As far as the turning of HWFI into an "opportunity area" is concerned, a study in the files of the London Legacy Development Corporation (LLDC) – the body in charge of the very same post-Olympics regeneration – can be quite telling. A phrase tucked inside a small box reads: "We are currently considering how much affordable housing can be included in the scheme and are working towards a target of 10%."

As for the economic recovery that the Olympics were supposed to bring about thanks to the inflow of tourists, HWFI inhabitants have seen very little of it, since local authorities decided to close Hackney Wick underground station during the weeks that the Olympics were happening in order to direct travellers towards Stratford instead.

In short, if you lived in Hackney Wick or Fish Island before the Olympic Games and you cannot afford the type of apartment that starts at £400,000 for a studio flat, or if your family counts more than two members, then the chances of you remaining in your family home rest at around one or two in ten.

In fact, LLDC owns an increasing amount of land in Hackney Wick where it has planning powers that allow it to buy what it doesn't already own thanks to the all-powerful Compulsory Purchase Order.

You could decide to stay and become poorer as rents go up, struggling to make ends meet while you see people around you drinking £5 frappuccinos and think (wrongly) that the owners of such hipster cafés or resident artists are the cause of your problems. While the former are but the symptoms of a deeper mechanism, the latter are often victims of gentrification themselves.

History repeat

"In general, artists in London look for lower rents than other social and professional categories," says Richard Brown who, through his Affordable Wick initiative, addresses artists' responsibility towards their communities, "At the moment we have a big problem because it is clear that artists and creative types are responsible for the current sharp rise in prices in Hackney Wick. Artists make a place like this much more acceptable and attract an economy that is not accessible to many of its long-term inhabitants."

First and foremost, it would probably be a good idea to distinguish between the two facets of this phenomenon. In HWFI, the most obvious and criticised facet is doubtless the so-called place-marking: a sophisticated mechanism that seeks to turn a neighbourhood into a brand in order to "sex it up", in particular through the use of lifestyle media or the direct implementation of fashionable shops.

In general, artists, whether wittingly or unwittingly, are accessories to the process that, sooner or later, ends up forcing them out of their own area. Faced with an invasion that hides behing a mask of "cool", resistance gestures are flourishing in HWFI in an uncoordinated, sometimes incongruous, fashion. The best known remains the famous Keep Hackney Crap campaign.

But it is under the surface, in their less glamorous forms, that the real stages of this process are being played out – where the abstract financial figures of white-collar criminality cause very real social suffering. It is very convenient for those who actively work towards gentrification to claim that this is just a law of nature, like gravity or the certainty that you won't find any trace of seafood in a packet of fish sticks. They are the very same people who imply that the expulsion of the previous inhabitants in the name of regeneration is the only alternative available to an impoverished place.

But it is under the surface, in their less glamorous forms, that the real stages of this process are being played out – where the abstract financial figures of white-collar criminality cause very real social suffering. It is very convenient for those who actively work towards gentrification to claim that this is just a law of nature, like gravity or the certainty that you won't find any trace of seafood in a packet of fish sticks. They are the very same people who imply that the expulsion of the previous inhabitants in the name of regeneration is the only alternative available to an impoverished place.

Many HWFI inhabitants are calling for a regeneration based on better local organisation of infrastructure and security. But it is absurd that they should only get this in exchange for their own departure. Faced with this urban Darwinism, the idea that high rents are the last bastion against a fantasy urban chaos needs to be opposed. "Opposition to gentrification is rapidly becoming less marginal, and more organised," writes Dan Hancox in a Guardian column.

Otherwise HWFI will go down the same road as Shoreditch or Elephant and Castle already did a few years back. The working class were ruthlessly kicked out from those areas to make room for a social and cultural life beyond its means, one that looked suspiciously like a shopping centre. If not, the beautiful chaos of Fish Island will be reduced to little more than a few old bones.

---

This feature report is a part of our EUtoo 'on the ground' project in London, seeking to give a voice to disenchanted youth. It is funded by the European Commission.

Translated from Londres : Hackney Wick, Fish Island et l'ombre du cool