Lisbon treaty: French preach about the Irish vote

Published on

Translation by:

Susannah Readett-BayleyMany partisans of European construction were grieved – the French the first. However, Kouchner and his preaching cronies only rubbed the Irish up the wrong way – the Irish with the chance to decide

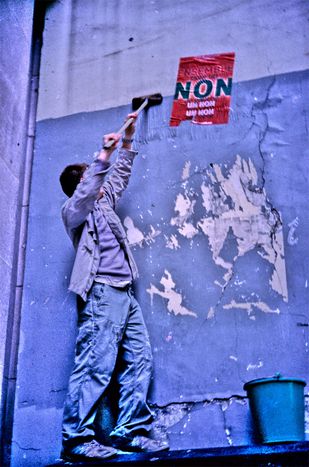

‘I'm more than upset, I'm devastated,’ declared Jean-Pierre Jouyet, the French secretary of state for European affairs after the Irish referendum results were announced on a certain Friday 13th. 53.4% of the Irish population voted ‘No’ (‘Nil’ in Gaelic), therefore refusing to ratify the Lisbon Treaty, signed in 2007 after twelve years of negotiation and three successive texts (Amsterdam 1997, Nice 2000 and the constitutional treaty of 2004).

Pro-Europeans are not only faced with the indignity. They also want to understand; was it due to media influence, particularly from the media mogul Rupert Murdoch, or was it due to the ‘no-vote’ lobbying by the enigmatic 'Mister No', Declan Ganley? Or do we owe the no-vote to a misunderstanding of the text and a lack of voter interest? It's one thing to ask questions, but altogether another to lack respect for our insular neighbours: France's articulation over the Irish decision and its forthright morality is a sensitive issue.

Kouchner has it all wrong

‘The most likely victims of a potential 'no' - which I don't believe will happen - are the Irish,’ estimated the minister of foreign affairs on 9 June. ‘It would however be a huge obstacle to honest thinking if we couldn't count on the Irish who have counted so heavily on financing from Europe.’

‘The most likely victims of a potential 'no' - which I don't believe will happen - are the Irish,’ estimated the minister of foreign affairs on 9 June. ‘It would however be a huge obstacle to honest thinking if we couldn't count on the Irish who have counted so heavily on financing from Europe.’

Fundamentally, this argument is undisputable: the lowest unemployment rate in the union, optimum growth and GDP says it all. However, perhaps because of their history, the Irish are petrified that anyone might tell them what to do. The good old French sermon, most of which was re-hashed and used by the anti-Lisbon treaty camp has in the end had the adverse effect. Even the 'yes' camp criticised the French attitude: ‘These issues are inappropriate, Irish voters are able to make up their own mind,’ indignantly declared the Christian Democrat leader Enda Kenny (Fine Gael, opposition party).

France can't talk

But how else to react faced with this bitterness towards the Irish who spit in the soup once they've finished eating? All the same, the moral lesson really doesn't really seem fair when it's coming from a country that in 2005 didn't exactly show much enthusiasm for the constitutional treaty and was the first to jump up and down at the suggestions of the Lisbon Treaty being ratified by parliamentary voice!

'France doesn't know it all'

Sylvie Goulard, president of the European movement in France agrees. ‘The Irish 'no' is no more scandalous than the French farmers 'no' in Brussels,’ she says. So, does the French attitude of derision towards the Irish self-determination explain the way the vote went? This remains to be seen. What is sure is that the morality has flown back across the Channel like a boomerang. Bernard Kouchner, ever lucid, prophesised whatsmore even before the Irish result: ‘France doesn't know it all.’

Complex presidency

The moral of the story is that the French presidency of the European union, which begins at the beginning of July, is from the start undermined by the no vote. The European leaders' position is however one of optimism. ‘Europe is neither in crisis, nor defunct,’ reassures Jean-Pierre Jouyet. Bernard Kouchner recommends displaying patience and waiting for the outcome from the nine countries still to ratify the treaty, in particular the Czech Republic whose president is, from the outset, against the treaty. It seems that French president Nicolas Sarkozy, who would have liked to be the cantor of the simplified treaty, will need to redirect his conception of the presidency and to rethink the relationship between the union its citizens' concerns.

Translated from Une french leçon qui irrite