Lisbon, London: the problem with SlutWalks or Who's afraid of feminine sexuality?

Published on

Europe has been celebrating three months of the Canadian-exported 'SlutWalks', with the next protest against the equation 'sexy clothing does not mean slut' taking place in Lisbon on 25 June. 11 June saw the phenomenon hitting British shores

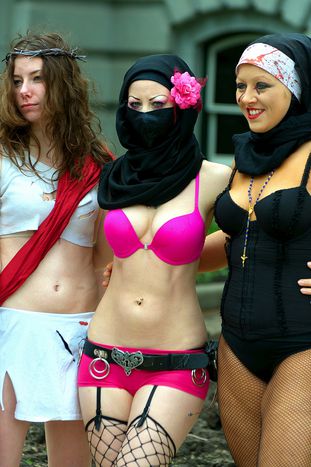

Men wearing nothing but short skirts and bras, middle-aged women with their daughters, a colourful transgender group in high heels and flashing earrings, lesbian mothers and women wearing burqas walked the streets of central London together on 11 June. Thousands, both scantily clad as well as carefully wrapped up for the imminent London shower, marched from Hyde Park Corner to Trafalgar Square in support for a recurrent cause. It has been coined as the incipient stage of the 'fourth wave of feminism'.

The meaningless trigger for this series of demonstrations sweeping through America, Europe and recently reaching Asia - the next Slut Walks are in Lisbon and New Delhi on 25 June - was a statement made by Toronto police officer Michael Sanguinetti while giving a campus safety talk at Osgoode Hall Law School. 'Women should avoid dressing like sluts in order not to be victimised,' he famously remarked, caused outrage in Canada. The first SlutWalk was organised in Toronto on 3 April, and the message is simple: sexual assault is an act of violence by the perpetrator and never something occasioned or asked for by the victim. Women's clothing or behaviour should never be used as an excuse for violence against them. 'Women are raped in all kinds of clothes,' states one of the London protesters, while one of the best banners read 'Little girls' clothes don't create paedophilia'.

Rape-a-penny

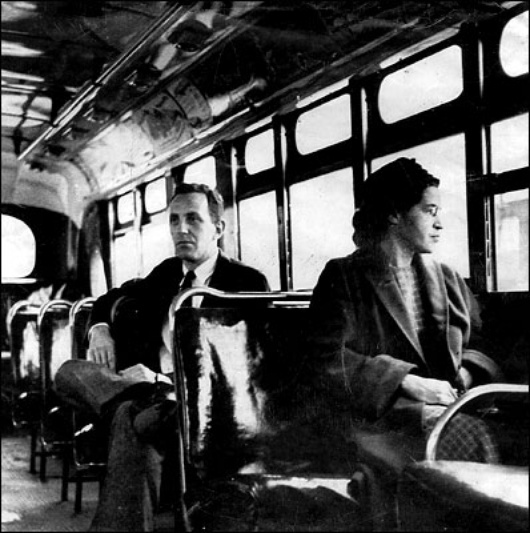

SlutWalks has been regarded as an overblown reaction to a meaningless slip of the tongue. Rosa Parks' refusal to move to the back of the bus by a white fellow passenger on 1 December 1955 was probably a mundane incident at the time. Nevertheless, we remember it today as having unexpected long-term effects after snowballing into the American civil rights movement. A speaker on BBC's Radio 4 recently argued in British broadcaster David Aaronovitch's Moral Maze, that had Mr. Sanguinetti been Ms. Sanguinetti, it wouldn't have caused public outrage.

SlutWalks has been regarded as an overblown reaction to a meaningless slip of the tongue. Rosa Parks' refusal to move to the back of the bus by a white fellow passenger on 1 December 1955 was probably a mundane incident at the time. Nevertheless, we remember it today as having unexpected long-term effects after snowballing into the American civil rights movement. A speaker on BBC's Radio 4 recently argued in British broadcaster David Aaronovitch's Moral Maze, that had Mr. Sanguinetti been Ms. Sanguinetti, it wouldn't have caused public outrage.

This has as much relevance as arguing that if the civil rights activist had missed that bus, the movement would never have started. A mundane event acquires the energy to become a trigger for a social movement only when society is ready to acknowledge that specific fact as bearing a certain symbolic weight. It is not the trigger that makes the masses march, but the social group that reaches the state of maturity to actually identify the trigger as such. In a radio interview on 18 May, British justice secretaryKen Clarke made a distinction between 'serious rape' and 'other' types of rape while presenting the government's intention to offer lesser sentences for rapists who plead guilty early. In Britain, the minimum sentence for (a 'not-so-serious') rape is only four years, whilst only 6% of reported rapes in Britain end in conviction.

Call me

The message seems to be clear and straight-forward enough. Yet in the great tradition of feminism the issue has centred on the name of the marches and the method used as means of empowerment for women. In Britain, moral self-righteousness swept through the media the moment we heard the news of the London SlutWalk. The Gordian knot regarded women's reluctance to identify as sluts in an over-sexualised culture (where value still lies with attractivity and young girls' sexuality), is constantly being commodified. In several media debates, women expressed concern over internalising images of sexual objectification and stated that dressing up as porn stars is a step back for feminism.

'By using the word slut so often we feel we have taken some of the power out of it'

One SlutWalk organiser explains the rationale behind choosing the word 'slut' as the march tag line. 'We are using the word slut because that is the word the officer used. By using it so often we feel we have taken some of the power out of it. It can't hurt us anymore,' says Caitlin Hayward-Tapp. The intention behind the use of this word has nothing to do with women internalising their role as sexual objects, nor with condoning loose moral standards. It is the expression of a trauma which still interferes with women's wholesome subjectivity construction. The moment feminine sexuality is brought into discourse, various normative injunctions populate the scene, regulating every aspect of something that hasn't even been fully articulated yet. Linguistic reappropriation is a delicate but painful process. It involves bringing back a pejorative into acceptable usage by a community which experienced oppression under that word. This reverse discourse reclaimed words such as 'nigger', 'jesuit', 'gay' or 'queer'. Now it's time for 'slut'.

One of the panellists on David Aaronovitch's programme emphasises that women's provocative clothing asserts their sexual availability. The problem seems to lie not with clothes inviting rape, but with the idea that women have at all a sexuality which they might wish to express. Feminine sexuality has been articulated for so long as the object of the male gaze, that we reached the point where, for both women and men, it has become outrageous to acknowledge that women are identifying themselves as sexual beings. Why should it be frightening? Should women not wish to have sex? The answer depends on the framework. If we follow the guidelines of masculine desire, an unattainable object is far more enticing than an accessible one. If we choose to acknowledge the impossible – that there is such thing as feminine desire - the answer might take a different shape.

Images: main (cc) bulliver on Flickr and official site; Rosa Parks on a bus with reporter Nicholas C. Chriss (cc) Wikimedia; Barbie (cc) Anton Bielousov on Flickr and his official site; Video (cc) SlutwalkLondon