Leman, Penguen or Uykusuz: Turkey's comic books vs. Erdoğan

Published on

Translation by:

Marie JacksonUtter the names of these satirical comic magazines in the presence of any Turk and their eyes will light up with recognition. Yet these publications are a serious thorn in the side of the government. Despite tough conditions and government repression, the cartoonists tirelessly put pencil to paper in the name of social critique

‘Two months ago, somebody tried to burn down the Penguen editorial office,’ explains Emre Yavuz. Suddenly I understand; just a day earlier, I had tried to catch a glimpse inside the satirical magazine’s offices without prior appointment - without success. Since the arson attack attack (nobody on-site believes that this was an accident), people in Istanbul understandably feel a little nervous. I won't face any such problems today; I have an appointment with Yavuz, editor and translator for the satirical magazine Uykusuz (‘Wakeful’), and I'm about to be received at the editorial HQ. ‘We prefer to call Uykusuz a satirical magazine, but really we're a comic book,’ he says.

Indeed, a significant number of the stories in the magazine are not told in a single cartoon, but through a series of comic strip episodes. That is not to say that Uykusuz shies away from political controversy in Turkey; nevertheless, it avoids prominent house advertising on the doors of the office. A single logo in the corridor betrays the presence of the 22 in-house cartoonists. This discretion is a precautionary measure against those who express their criticism of the magazine by less peaceful means.

Getting under the Sultan's skin

Yavuz's fellow comrades-in-arms have in fact chosen a noble vocation. After all, cartoon criticisms of the Turkish state are a long-standing tradition. Even in the late nineteenth century, the bulky nose of the last sultan, Abdülhamid II, provided easy pickings for derisive cartoonists. His subjects’ jokes displeased the Ottoman leader so much that he quickly forbade the written form of the word ‘nose’. This, of course, gave rise to a whole new wave of caricatures. Despite its earlier popularity, however, the cartoon wouldn't experience its golden era for another 70 years; the late Oğuz Aral’s cartoon magazine Gırgır (‘Fun’) sold up to 500, 000 copies per week during the seventies and eighties. Aral was also a committed teacher, having taken legions of comic strip enthusiasts under his wing. Sooner or later, many of his fledgling cartoonists flew the nest and founded their own comic books. Today, Leman magazine, Penguen and Uykusuz to name but a few, are household names in Turkey. Even though their content can sometimes raise an eyebrow, few kiosk owners would dare to stop selling these popular magazines. Gırgır was so successful because the magazine provided an outlet for criticism of the Turkish state and society at a time when all political parties were prohibited.

Yet the military government at the time, which was otherwise heavy-handed when it came to dealing with the opposition, largely let the cartoonists be. ‘They also read Gırgır and laughed at its cartoons,’ asserts Cenk Könül, an employee of Gon, one of the few comic book shops in Istanbul. But those times are now over. ‘Since the justice and development party (AKP) took power (in 2002 - ed), something has changed,’ claims 30-year-old Könül, describing the rising concern of cartoonists everywhere. ‘You can't just see and hear it, you can feel it.’ Whether they were religious, Kemalist, conservative, left-wing or democrat - where dissidents were previously tolerated, there is an increasing tendency today for people to do all they can to distance themselves from one other. Könül's older customers have already confirmed as much: ‘They say that the artists used to be gutsier, that they wrote and drew more audacious content.’

Yet the military government at the time, which was otherwise heavy-handed when it came to dealing with the opposition, largely let the cartoonists be. ‘They also read Gırgır and laughed at its cartoons,’ asserts Cenk Könül, an employee of Gon, one of the few comic book shops in Istanbul. But those times are now over. ‘Since the justice and development party (AKP) took power (in 2002 - ed), something has changed,’ claims 30-year-old Könül, describing the rising concern of cartoonists everywhere. ‘You can't just see and hear it, you can feel it.’ Whether they were religious, Kemalist, conservative, left-wing or democrat - where dissidents were previously tolerated, there is an increasing tendency today for people to do all they can to distance themselves from one other. Könül's older customers have already confirmed as much: ‘They say that the artists used to be gutsier, that they wrote and drew more audacious content.’

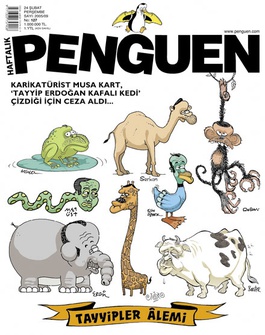

Humourless tomcat Erdoğan

One thing is clear. Prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan can rival old Sultan Abdülhamid II when it comes to lacking a sense of humour. As early as 2005, the prime minister sued Cumhuriyet magazine caricaturist Musa Kart for his drawings, deemed to be too critical of the government. Kart had drawn Erdoğan as a cat that was helplessly tangled in a ball of wool – a commentary on the pitfalls of government politics. The prime minister, considering that he was being vilified, took the cartoonist to court for libel – and won. Kart had to pay the prime minister 5, 000 Turkish lira (approx. 2, 300 euros). The cartoonists hit back, resulting in a further court summons. This time, though, the courts decided in favour of the cartoonists.

One thing is clear. Prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan can rival old Sultan Abdülhamid II when it comes to lacking a sense of humour. As early as 2005, the prime minister sued Cumhuriyet magazine caricaturist Musa Kart for his drawings, deemed to be too critical of the government. Kart had drawn Erdoğan as a cat that was helplessly tangled in a ball of wool – a commentary on the pitfalls of government politics. The prime minister, considering that he was being vilified, took the cartoonist to court for libel – and won. Kart had to pay the prime minister 5, 000 Turkish lira (approx. 2, 300 euros). The cartoonists hit back, resulting in a further court summons. This time, though, the courts decided in favour of the cartoonists.

When the magazine Harakiri, the latest addition to Turkey's roster of satirical cartoon magazines, was served a fine, it was nearly ruined. In summer 2011, the owners had to pay a fine of 150, 000 Turkish lira because their cartoons would supposedly ‘cause the Turkish people to become lazy and adventurist’ and ‘promoted adultery’. At least, that is how the commission for the protection of minors from indecent publications saw things. The government organ recommended henceforth that the magazine be sold in opaque packaging to protect innocent eyes. The Harakiri editorial office continued its work, even though it faced financial ruin, but an entire year passed before it was able to publish a new edition in July 2012. Könül made sure that the new magazine edition was displayed at the very front of his window. In the top-right-hand corner, a short and defiant statement popped out: ‘Poşetten döndük! – Now without packaging!’

‘We will continue moving forward, just as we did before, and we will continue dealing with matters of society in the magazine’

Tuncay Akgün is familiar with the gruelling Turkish court process. The clock strikes eleven as the 50-year-old finally arrives at the Leman editorial office. In 1987, Akgün was handed a suspended prison sentence as head of Leman's forerunner magazine, Limon (‘Lemon’), and the chief editor has already been sued again by the new government for images appearing in Leman. The magazine has had to fork out money twice now, and further proceedings have been stopped once already. In spite of this, Akgün refuses to bow to increasing pressure. ‘We will continue moving forward, just as we did before, and we will continue dealing with matters of society in the magazine,’ he says.

This includes the so-called ‘honour killings’, a reference to the stories of Kurds who supposedly commit unspeakable domestic violence against women. This independence does come at a price, however; in order to continue discussing ‘hot topics’, Akgün avoids advertising his magazine and regularly works a Sunday night shift. Despite this, Akgün's place of work – unlike the editorial offices of many other magazines – is not hidden away; clearly visible from the main high street in the shopping district and accessible to all is the Cafe Leman Kültür, located beneath the magazine's editorial offices.

Within these walls, decorated all over with comic strips and old Leman editions, all are welcome, from comic book fans and lateral thinkers, to left-wing activists and critics of Erdoğan himself. Here, they can talk together or simply browse their latest comics in peace. But what if some madman also pays a visit here, lighter or goodness knows what else in hand? ‘Ach,’ says Tuncay Akgün, rolling himself a cigarette, ‘didn't you know? The lord protects small children and comic strip artists!’

*Gon shop, Yeni Çarşı Caddesi 34A, Galatasaray

This article is part of the fifth edition of cafebabel.com’s flagship project of 2012, the sequel to ‘Orient Express Reporter’, sending Balkan journalists to EU cities and vice versa for a mutual pendulum of insight

Images: main © penguen.com; in-text © Jens Wiesner for 'Orient Express Reporter Istanbul' by cafebabel.com, July 2012

Translated from Zeichnen gegen Erdoğan: "Gott beschützt kleine Kinder und Comiczeichner!"