Laszlo Tengelyi: the problem of being a philosopher in Hungary

Published on

On 8 January Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orban launched an investigation into the use of grant money awarded to five philosophers. Questions to a Hungarian-born philosopher who spearheaded an international petition, 'Protect the Philosophers!' from Germany, where he is based

In 2010 Radnóti Sándor (professor of philosophy at the Eotvos Loránd university in Budapest, ELTE), Heller Ágnes (professor emerita from the new school for social research, NSSR), Vajda Mihály (former director of the institute for philosophical research at the Hungarian academy of sciences, MTA), Gábor György (professor at Budapest university of jewish studies) and Geréby György (professor of medieval studies at the central European Uuniversity in Budapest, CEU) were accused of misspending public funds of 440 million florints (1.1 - 1.4 million euros), which came from an innovation fund within the national office for research and technology.

The move was decried as a form of 'state harassment' targeted at scholars outspoken against the policies of the prime minister. A global community published an open letter signed by 60 world-renowned academics including nobel laureates. High-profile German philosophers Juergen Habermas and Nida Ruemelin evencalled on the EU to probe the case and ensure 'moral fundamental rights in Europe'. Fears are increasing that these investigations are the symptom of a more worrisome repression throughout the cultural sphere of a country that currently holds the six-month presidency of the council of the European Union. There is no word yet on the outcome of the investigations, but the Hungarians are not backing down on either side. Interview.

cafebabel.com: Laszlo, what is this issue actually about?

Laszlo Tengelyi: After the turn in 1989 until 2010, scholars and academics were treated as in western countries. Under a ruling socialist-liberal coalition scientists of all branches and scholars from the humanities could apply for relatively generous research grants (in 2004 and 2005, about 360, 000 euros for three years in the humanities, ten times as much in natural sciences). This 'national endowment' was originally created in 2001 under the first rule of the conservative young democrats, Fidesz, by József Pálinkás, then-culture minister and current president of the Hungarian academy of sciences (MTA). Today, six grant applications have been singled out. According to the Magyar Nemzet ('Hungarian Nation'), a newspaper tied to the right-wing Fidesz government, they belong to a 'liberal circle' of philosophers considered as a beneficiary of the former government. A police investigation was initiated against four research projects in January and February. The entire system for distributing this money is not being investigated (although the government has recently declared an intention to inquire into ten further research projects).

How does this fit into the broader context of the nation's current spirit or current government?

Laszlo Tengelyi:Fidesz was elected in April 2010 with 53% of the votes and a two-thirds majority in parliament. They have passed several laws that contribute to a dismantling of democratic institutions in Hungary. A media law incompatible with European norms was only the tip of the iceberg: the constitutional court’s jurisdiction has been severely restricted, the so-called ‘budget council’ was replaced with a new body run by a president who is a Fidesz party adherent and the chief prosecutor is another well-known Fidesz partisan. A law passed by the Hungarian parliament half a year ago means those working in the state administration could be dismissed en masse without explicit justification.

This populistic touch is a new tone in Hungarian public life

Fidesz relied on layers of the population that had played no significant role in the formation of political opinion since world war two. In 2006, this populistic turn led to a certain cooperation with some right wing organisations in mass demonstrations against the coalition. This populistic touch is a new tone in Hungarian public life, characterised by resentment, agression, nationalistic prejudice and an anti-semitic mood. It's part of this new tone to disparage philosophy, as well as contemporary art, cinema, theatre, and even to oppose musicians like Zoltán Kocsis, András Schiff or Iván Fischer, because of political reasons.

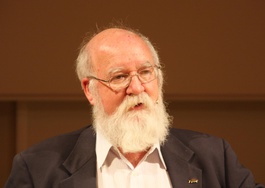

What do you make of the involvement of the international academic community? For example, American philosopher Daniel Dennett retracted his signature on the open letter to the MTA in early February.

Laszlo Tengelyi: It’s an inconvenient episode. It's all the more deplorable as the interventions of the international academic community were exerting their influence on Hungarian political life. It is difficult for western scholars to form a reliable picture of a controversy, in a language they do not understand. They are compelled to rely on acquaintances. However, now the campaign is continuing on a higher level and new interventions are needed. Nine major philosophical societies in Germany have signed an open letter to the Hungarian prime minister and the president of the MTA.

What is a likely outcome of the events?

Laszlo Tengelyi: A series of trials against at least some of the accused philosophers. In Hungary, even the most inveterate juridical principles are not always respected.

But would Hungarian philosophers leave the country? Why did you yourself decide to teach abroad ten years ago?

Laszlo Tengelyi: The older generation are in a position to do so, but by no means want to yield to such a constraint. The younger generation will do everything in order to get an appointment in one of the western countries, a natural option for an east central European scholar who has recently become citizen of the European community.

In 2001 I applied for a professorship at a German university when I was already a professor at the Eötvös university of Budapest. Back then it was to continue my research and teaching on a higher level, and taking over and carrying on the intellectual heritage of my predecessors. But now the significance of this alternative will be greatly enhanced by obvious political reasons.

Three questions to Daniel Dennett

cafebabel.com: Daniel, how did the information that you esteemed relevant to your decision come to light?

Daniel Dennett: Academic friends in Hungary from a number of different disciplines emailed me with some details, telling me that I had heard only one side of the story. Since I had good, trusted friends taking opposite views of the situation I had to withhold judgment. I don’t know enough and cannot readily learn enough to have an informed opinion about where the balance of truth lies.

Daniel Dennett: Academic friends in Hungary from a number of different disciplines emailed me with some details, telling me that I had heard only one side of the story. Since I had good, trusted friends taking opposite views of the situation I had to withhold judgment. I don’t know enough and cannot readily learn enough to have an informed opinion about where the balance of truth lies.

cafebabel.com: You mentioned that your decision was based partly on having been involuntarily involved in a ‘polarised atmosphere’. Is it grounds for a retraction?

Daniel Dennett: If it had been a matter of asking a few more trusted informants and reading a few dozen reports, I could and should have done so, but I don’t read Hungarian, had pretty well exhausted my sources and was nowhere near well enough informed to vouch for anything aside from the principles.

cafebabel.com: Do you think the philosophers in Hungary who claim they are being persecuted deserve or need the support of the international academic community. Does this community have a moral obligation or a responsibility to be vocal about their support?

Daniel Dennett: The philosophers who claim they are being persecuted deserve to be listened to carefully, and their claims should be investigated vigorously and impartially—by people who have the competence to investigate them. Whether they all, or individually, deserve further support is precisely what is at issue, and I don’t know the answer to that question.

Images: main (cc) Josh Pesavento (broma)/ joshpesavento.com/ Flickr; Daniel Dennett pictured in Germany in 2008 (cc) Mathias Schindler on Wikimedia