Kosovo discontent in Serbia

Published on

Translation by:

Sarah GrayFeeling that they are nothing more than a transition generation, young Serbs are losing interest in politics. But the lively debate goes on in bars and restaurants. Final diary from a three-part travel series

I have no fixed ideas about what I’ll see and photograph in Belgrade. So much the better, in fact, to head there blindly, and amongst friends. Thanks to the magic of the internet we’ve already made contact with some Serbs: students, people organising parties, associations and societies.

Resignation after dictatorship and silence

Belgrade Airport, 10am. Straightaway, our first surprise: the faces of the two main political candidates, Boris Tadic (democratic party) and Tomislav Nikolic (Serbian radical party), on every advertising billboard. We finally reach our youth hostel, run by Donovan, a young white American and convert to Islam. From then on we meet lots of people, live a strange rhythm with no difference between day and night, and encounter seemingly contradictory views. ‘We can’t see a way out. We have been ‘in transition’ for years, for nothing,’ chime alongside ‘It’s too late for our generation’. Many associations and student organisations are trying to fight exactly this type of lack of enthusiasm and loss of self-confidence. They were set up in opposition to the silence imposed when Yugoslav president Slobodan Milosevic was in power.

Belgrade Airport, 10am. Straightaway, our first surprise: the faces of the two main political candidates, Boris Tadic (democratic party) and Tomislav Nikolic (Serbian radical party), on every advertising billboard. We finally reach our youth hostel, run by Donovan, a young white American and convert to Islam. From then on we meet lots of people, live a strange rhythm with no difference between day and night, and encounter seemingly contradictory views. ‘We can’t see a way out. We have been ‘in transition’ for years, for nothing,’ chime alongside ‘It’s too late for our generation’. Many associations and student organisations are trying to fight exactly this type of lack of enthusiasm and loss of self-confidence. They were set up in opposition to the silence imposed when Yugoslav president Slobodan Milosevic was in power.

‘We have to work tirelessly to change things, to take control,’ says one of the militants. What about Europe? There again opinions are divided. Some see it as an empty shell that only serves the interests of the US and NATO. Others claim it’s the only chance for Serbia to get out of its torpor.

Kosovo: a sensitive area

Kosovo remains the most sensitive subject. For some, it’s the birthplace of the Serbian nation and should never be abandoned. For others it’s a lost territory where 90% of residents are now Albanian, which needs to be given up in order to focus elsewhere. It’s a strange battle. Certain remarks are shocking, even aggravating. But some interviews are completely open and respectful and justified in their logic. We represent France, and therefore part of the west. We suffer the consequences, the bitterness towards our past policies and our current absence.

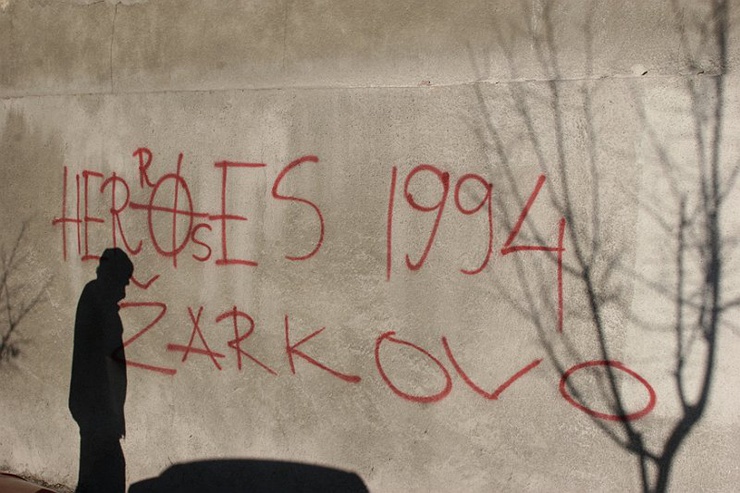

Amongst the remains of buildings bombed in the NATO-led war against the Yugoslav regime in 1999, the fog is lifting to give space to more cheerful scenes. Near the city centre we find an ice-skating rink where people start dancing by the Danube, and start to forget the tangled complications of the Balkan region. We arrive at a restaurant where the guests rise to dance to the music playing, a mix of Balkan folk music and modern rhythms which warms their hearts. It’s late, and the remaining customers are now sitting around the same table; a Greek couple and some Serbs and Croats. Their raise their voices over the noise of trumpets, discussing the Balkans and their former glory. Everyone makes the others taste their local variety rakia, a classic scene in Belgrade. It’s difficult to understand each other but their expressions are enough.

Amongst the remains of buildings bombed in the NATO-led war against the Yugoslav regime in 1999, the fog is lifting to give space to more cheerful scenes. Near the city centre we find an ice-skating rink where people start dancing by the Danube, and start to forget the tangled complications of the Balkan region. We arrive at a restaurant where the guests rise to dance to the music playing, a mix of Balkan folk music and modern rhythms which warms their hearts. It’s late, and the remaining customers are now sitting around the same table; a Greek couple and some Serbs and Croats. Their raise their voices over the noise of trumpets, discussing the Balkans and their former glory. Everyone makes the others taste their local variety rakia, a classic scene in Belgrade. It’s difficult to understand each other but their expressions are enough.

Translated from Sur la route serbe (III) : entre désillusion et nostalgie