Kosovo declared independence one year ago. Is the region really destabilised?

Published on

As the authority of the world’s newest country moved to the EU, Belgrade asks the international community for a role in shaping Kosovo's future. But there are signs that the government would like to put the issue aside

In June 2008, after nine years of UN rule, the majority ethnic Albanian government took power. In December, the UN passed police, justice and customs to the long delayed EU mission Eulex. On 21 January, the Kosovo Security Force, a de facto national army, replaced the mostly unarmed, UN-regulated Kosovo Protection Corps. Since 17 February 2008, 54 UN members have recognised Kosovo. On 9 February five EU countries including Spain, Greece, Romania, Slovakia and Cyprus maintained their refusal to do so, unless an agreement with Serbia were reached.

Belgrade’s moves, Kosovo’s divides

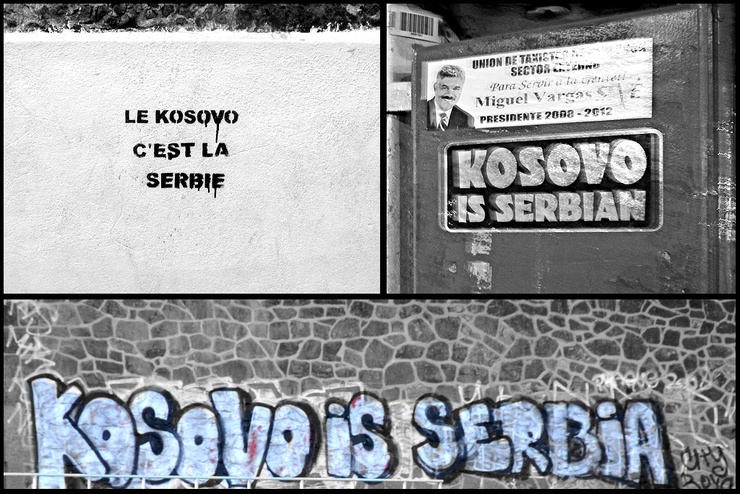

Serbia's moves on the international scene as well as in Kosovo are frustrating Pristina's efforts. By funding parallel health, education and social security structures, Serbia keeps Kosovar Serbs out of the reach of Albanian authorities. In March, Kosovar daily Koha Ditore reported that Belgrade had allocated around 50 million euros (£44.79 million) to pay Kosovar Serbs working for their government. In June, a rival assembly was set up in the ethnically divided town Mitrovica. Serbia's office in Gracanica issues Serbian passports. These keep Kosovo divided along ethnic lines.

In November, Serbia's six-point plan for Eulex won UN Security Council backing. But instead of confirming Kosovo's independence, the EU mission deployed as status-neutral. In an interview for the Belgrade BETA agency on 14 November, Serbian president Boris Tadic rejoiced: ‘Eulex ensures the functioning of resolution 1244, the only international act that asserts Serbia's integrity.’ Serbia would have ‘sufficient instruments to influence the situation in areas populated by Serbs.’

Serbia in the EU

Could Serbia get candidate status as soon as the end of 2009? The EU 2008 progress report stated that Belgrade significantly advanced in a key requirements for EU membership - full co-operation with the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY). But neighbourly relationships are another requirement.

Co-operation but also 'neighbourly relationships' are requirements for EU membership

The EU already used the ‘membership carrot’ in April when it offered Serbia the ‘Stabilisation and Association Agreement’ (SAA) to bolster - successfully - Tadic’s chances in the May parliamentary elections. His pro-European government left behind the stubborn position of ex-PM Vojislav Kostunica and opened to talks. Belgrade reinstated the ambassadors it had earlier pulled out of the countries that recognised Kosovo. It sought the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to rule on the legality of Kosovo's independence.

Dusted

But the ICJ will take several years to review the case, whilst Serbia can focus on joining the EU – Tadic's big goal. Belgrade believes that this can happen without status being settled, as in the 2004 Cyprus case. Serbia is limited to asking those that have not recognised Kosovo to submit their opinion to the ICJ, or blocking Pristina's membership of international organisations. ‘Kosovo will not be a member of the UN or the OSCE. It will not belong to the world community of sovereign nations,’ the AFP quoted Serbian foreign minister Vuk Jeremic as saying on 28 February 2008.

But the ICJ will take several years to review the case, whilst Serbia can focus on joining the EU – Tadic's big goal. Belgrade believes that this can happen without status being settled, as in the 2004 Cyprus case. Serbia is limited to asking those that have not recognised Kosovo to submit their opinion to the ICJ, or blocking Pristina's membership of international organisations. ‘Kosovo will not be a member of the UN or the OSCE. It will not belong to the world community of sovereign nations,’ the AFP quoted Serbian foreign minister Vuk Jeremic as saying on 28 February 2008.

Belgrade hopes that after it joins the EU and the ICJ makes its ruling, it will get Kosovo back. In an interview for Belgrade news agency FoNet on 2 January, Tadic added that Serbia was thinking about a solution for Albanians as well as the Serbs in Kosovo. The EU is likely to push Serbia to make some concessions, as French foreign minister Bernard Kouchner has indicated.

Until the ICJ delivers its verdict, no big moves are likely to come

European countries are not united in their stance so the EU can hardly impose. Serbian popular daily Blic quoted that if Kosovo’s north unites with Serbia, the EU and US might turn a blind eye, were the south recognised. Tadic said that partition ‘is not on the agenda’ in an interview for the Belgrade RTS on 29 September. But ‘everything is better than one getting it all and the other losing it all.’ Until the ICJ delivers its verdict no big moves are likely to come. Kosovo will probably gain no further recognition. If Serbia becomes an EU member or Kosovo succeeds in integrating the Serb minority, there could be a shift in positions.