Kasparas Pocius, not quite the father of Lithuanian anarchism in the millenium

Published on

The 27-year-old is too young to be fairly branded the 'father' of Lithuanian anarchism today. However, as one of the co-founders of anarchija.lt, the critical magazine Juodraštis ('Draft') and the Vilnius Free University, he is the most visible public figure when it comes to presenting Lithuania's anarchist ideas to the wider public

Kasparas Pocius resigns himself to being a 'precariat' – one of a large stratum of people who have no guaranteed job nor sustainable income. ‘It's insecure, but it’s exactly at the moment when you escape from the illusionary routine security offered by the 'spectacle society' that plenty of opportunities to improvise and experiment open up,’ he explains. In a society which stigmatises most leftist political ideas and does not seriously get involved in ‘non-formal communal initiatives’ - like the Vilnius Free University (Laisvasis universitetas, LUNI) - how does an anarchist grow?

The 27-year-old remembers going to the Lithuanian pro-independence demonstrations as a child and seeing the Singing Revolution of the Baltics (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania’s pre-independence period, 1987 - 1990 - ed). ‘I observed the degeneration of things which seemed endlessly democratic and solemn,’ he says, explaining his disillusion with the ideals of the first years of Lithuanian independence. ‘Euphoria was soon replaced by ‘real capitalism’, consisting of primitive accumulation or fraud on a national level. Meanwhile, alienation and the privatisation of consciousness eradicated the remnants of a collective consciousness.’

From Seattle to Paris: global inspiration

What events influenced him and other anarchists in Lithuania? Kasparas starts his story in Seattle. 'On 30 November 1999, social movements staged quite a 'ball' for the powerful ones attending the world trade organisation ministerial conference,’ he says. The convention was being held to launch a new round of trade negotiations. ‘Capitalist institutions got a strong blow, public opinion started doubting the ideology of the free market, the vices of capitalist globalisation were discussed, alternatives were sought. It was this globally famous event - which is comparable to the fall of the Berlin wall - which helped the formation of critical thought in Lithuania.’ Criticism towards the emerging consumer society and Lithuania's uncritical support for what Pocius calls the ‘US New Order model’ gained momentum in the new millenium. ‘In around 2000, punk activists in Vilnius organised anti-Nato activities, showing an emerging global consciousness and sensitivity to what was happening in the world. And then there was 2005, and the story of the Lietuva cinema, which allowed the uprising of a colourful civic movement in the country.’ The cinema, popular among the youth for its alternative orientation and exciting festivals, was closed by its new owners, who bought it from the municipality for a reduced price during the massive privatisation campaign. The excuse for closing the cinema was that it 'brought no profit.'

What events influenced him and other anarchists in Lithuania? Kasparas starts his story in Seattle. 'On 30 November 1999, social movements staged quite a 'ball' for the powerful ones attending the world trade organisation ministerial conference,’ he says. The convention was being held to launch a new round of trade negotiations. ‘Capitalist institutions got a strong blow, public opinion started doubting the ideology of the free market, the vices of capitalist globalisation were discussed, alternatives were sought. It was this globally famous event - which is comparable to the fall of the Berlin wall - which helped the formation of critical thought in Lithuania.’ Criticism towards the emerging consumer society and Lithuania's uncritical support for what Pocius calls the ‘US New Order model’ gained momentum in the new millenium. ‘In around 2000, punk activists in Vilnius organised anti-Nato activities, showing an emerging global consciousness and sensitivity to what was happening in the world. And then there was 2005, and the story of the Lietuva cinema, which allowed the uprising of a colourful civic movement in the country.’ The cinema, popular among the youth for its alternative orientation and exciting festivals, was closed by its new owners, who bought it from the municipality for a reduced price during the massive privatisation campaign. The excuse for closing the cinema was that it 'brought no profit.'

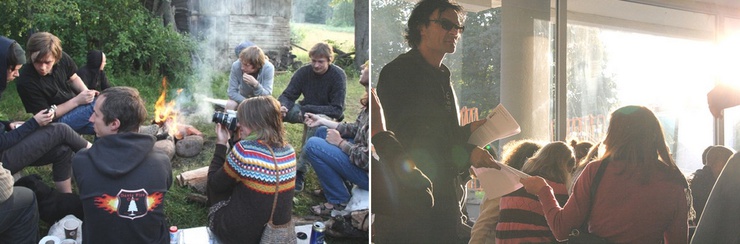

'The Vilnius Free University helped make the experiences of France in 1968 relevant again'

Pocius fondly remembers the time when a critical mass of people fought the penetration of business into public spaces together, despite their differing values. ‘We organised two conferences devoted to the issues of the modern left, to bring the key issues of the world closer to our local leftists. The Kitos knygos ('Other Books') publishing house published radical political fiction which triggered the social sensitivity. So alongside translator Darius Pocevičius and publisher Gediminas Baranauskas, I created the media portal anarchija.lt, which organises various political and cultural actions. In 2008 we established the Vilnius Free University, which serves as a balance to the neoliberal, 'rogue' reforms in higher education. It helped make the experiences of France in 1968 relevant again.’

anarchija.lt

‘I’ve always been more attracted to the streams of anarchism which highlight the importance of community, not the individualistic streams,’ Pocius says. His anarchija.lt portal was created as a counterbalance to 'corporate media' by supplying news about the anti-capitalist movement in the world. ‘It stands for people independently joining communities, collectively using the means and fruits of their labour, mutual help, emancipation and equality – all of which are prerequisite in the maturing of a free and critical personality,’ Pocius maintains. ‘We are proud that the portal serves as the Lithuanian Indymedia,’ he adds. He remembers the threats from several MPs to sue the portal, because they confused anarchists with soviet communists, despite the clear anti-stalinist stance of the former. ‘In May the portal was attacked by hackers. However, our active sensitivity and will allows us to forget the grievances and not to pay attention to paranoid, all-fearing wrongdoers.’

'With the current crisis in Lithuania, we should remember one piece of advice from the autonomists: let's refuse to work'

The 19th century Russians, Mikhail Bakunin, a ‘collective anarchism’ theorist, and Pyotr Kropotkin are two of Pocius’ inspirations. He cites 'optimistic' authors such as Antonio Negri, Paolo Virno and Nick Dyer-Witheford, who pin-pointed sixties autonomist marxism in Italy. He also mentions more 'pessimistic' influences, such as Franco Berardi-Bifo, who recently lectured at the Free University. ‘With the current crisis in Lithuania, we should remember one piece of advice from the autonomists: let's refuse to work. In the past French situationists used to say: never work – create. The precariat I mention uses this slogan willy-nilly, which not only thrives in conditions of permanent insecurity, but also makes use of its advantages. It's time to start using the products of modern technological society instead of continuing to enduring the yoke of labour and exploitation.’ Kasparas mentions that Lithuania was not excluded from the eSeR movement (socialist revolutionaries) in Russia in 1910. However, authentic anarchists in Russia were crushed by the 'oracles of dictatorship of the proletariat' and their followers.

Today, Pocius keeps busy with the Free University, which in his words is 'an informal initiative for self-enlightenment'. The initiative has spread into various Lithuanian towns which had no previous access to higher education. He doesn’t regret quitting his history PhD at Vilnius University. ‘The skills that I gained as a historian help me in researching. Intellectual temptations don’t diminish beyond the limits of the 'serious' academia. Knowledge polishes itself, it reshapes itself into strategies for action.’ Today, he earns a living from translations. He opposes assigning his other voluntary activities to the realm of hobbies. He insists that what he does is serious work, which also shapes thinking and lifestyle. He hopes that in the 'communes of the future' he will retain his ideological backbone. His main short-term concerns are now taking care of his newly established family (Kasparas married a few days before this interview), and encouraging others to love life.

Read the author's blog, 'Wonderland',here