Journey to the centre of Paris: An evening with a cataphile

Published on

Translation by:

Natalia MierzewskaAround 20 metres underneath the sidewalks of Paris is a vast web of corridors: the catacombs. Only a small section of it is accessible to tourists - the rest is (illegally) explored by cataphiles. One of them agreed to be my guide.

We set up a meeting at the Denfert-Rocherau metro station, near the "official" entrance to the Paris catacombs. You could recognize my guide (let’s call him Pierre) at once; with his working clothes, a tourist’s backpack and waterproof boots up to his thighs. Everything he wears looks slightly worn out. The rest of the group looks perfectly normal. We’re mostly wearing sneakers and jeans and nothing except the headlamps in our backpacks could betray to anyone the reason for our meeting that evening.

When is a catacomb not a catacomb?

To tell the truth, the corridors we’ll be visiting have never really served as catacombs - that is to say, an underground cemetery. The only real catacombs are the ones that are open to tourists, plus a few corridors around the Montparnasse Cemetery, where human remains have been transported from the overcrowded 18th-century Parisian necropolis. The vast web, counting hundreds of underground corridors located mostly under the southern districts of Paris, was used to extract stone that served to build the City of Lights. The quarries were situated outside the city at first. As long as they were situated underneath fields and pastures, the subterranean corridors weren’t a source of concern.

But Paris was expanding. Townhouses were built atop a warren of tunnels, some of which had been abandoned for centuries. A particularly severe cave-in tore down several buildings in the winter of 1774, and King Louis XVI appointed the General Inspectorate of the Quarries - which still exists to this day - to dig their way into tunnels, reinforcing and mapping them.

Looking for the entrance

"Watch your heads," Pierre warns us. After hopping a fence and taking a ten-minute walk along some abandoned metro tracks, we arrive at a hole carved into the wall. There is an impressive stack of trash next to it. Cataphiles aren’t usually messy types but apparently not everyone takes the time to put their waste in the right bin.

For many seeking an underground adventure, finding an entrance constitutes the main challenge. It might be a manhole cover, a basement or a hole carved into the wall of a metro tunnel. But even a thorough Internet search is no guarantee of finding the information you need.

For many seeking an underground adventure, finding an entrance constitutes the main challenge. It might be a manhole cover, a basement or a hole carved into the wall of a metro tunnel. But even a thorough Internet search is no guarantee of finding the information you need.

"There’s one forum where you can find quite a few cataphiles, but they’re often distrustful and sometimes even aggressive," says Pierre. "If you ask them to be your guide or for information about access points, you will be called names." A visit on the forum in question confirms he’s telling the truth. There is even a thread called "Cemetery of ‘searching for a guide’ announcements." The process is always the same: the poor soul who dares to ask the question is first lead into answering questions about the reason for their visit and personal details, only to be later mocked in ways understandable only by the regular participants of the forum.

But cataphiles have good reason to be wary: journalists tend to focus on a false image of the underground community, focusing on the troublemakers and ignoring the ones who are truly passionate about their hobby. On the other hand "tourists" - as they dismissively call the Sunday explorers - are trouble. They want to have everything handed to them on a silver plate; showing up unprepared and often getting lost. Most cataphiles share a precious feeling of being chosen, possessing a knowledge that remains out of the reach of mere mortals.

So what is the best way to find an entrance to the catacombs? As is often the case in life, it helps to know the right people. Pierre is the roommate of a friend of a friend of mine, and he was introduced to the underground community by his own friends. "By the third time I went, I was the one bringing people along. Around the tenth time I started going on my own." It didn’t take long for him to get hooked, and he’s been a regular for three years now. Together with friends they now even plan to adopt one of the less accessible chambers for their own needs: a place of their own in the underground labyrinth.

Journey to the centre of the Earth

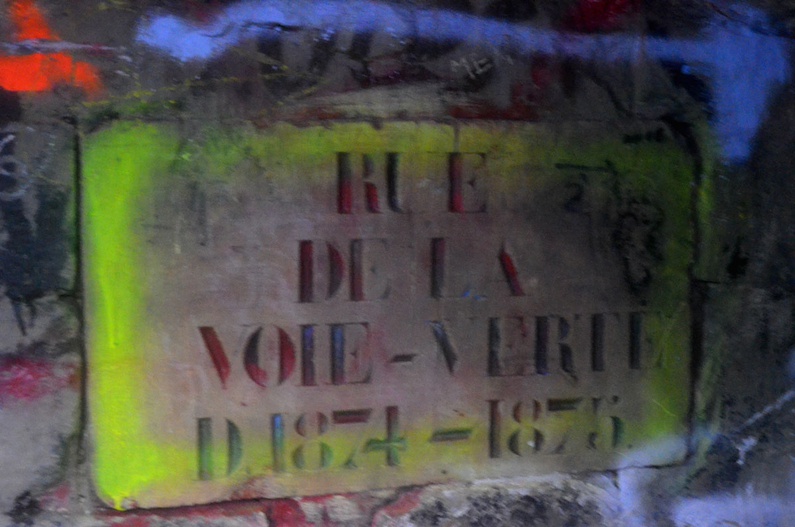

Once we’re underground, Pierre tells us where we are. "This is a corridor dug by the General Inspectorate," he says. "It’s not a part of the quarries." From time to time you can see inscriptions on the walls with dates and initials, sometime the names of the streets above. However, as this part of the city has been remodeled numerous times, you shouldn’t take these too seriously. To stay oriented in this labyrinth requires real skill. The 20m of stone above our heads blocks any Internet coverage, so we have to stick to using a map and compass. Even Pierre does this: “I check my map from time to time. I know the road, but it’s always err on the side of caution. If you have a really good map it’s really hard to get lost."

Once we’re underground, Pierre tells us where we are. "This is a corridor dug by the General Inspectorate," he says. "It’s not a part of the quarries." From time to time you can see inscriptions on the walls with dates and initials, sometime the names of the streets above. However, as this part of the city has been remodeled numerous times, you shouldn’t take these too seriously. To stay oriented in this labyrinth requires real skill. The 20m of stone above our heads blocks any Internet coverage, so we have to stick to using a map and compass. Even Pierre does this: “I check my map from time to time. I know the road, but it’s always err on the side of caution. If you have a really good map it’s really hard to get lost."

The further we go, the more puddles appear. I clumsily try to avoid them but Pierre just scoffs. "You can jump all you want but sooner or later you’ll get wet." Soon the water reaches my ankles. Then my calves. And finally my knees. Our guide is not impressed: "There are places in the 14th arrondissement where the water goes up to your neck. You can go swim there." Despite the wet clothes, we aren’t particularly cold. In the catacombs, the temperature stays more or less stable throughout the year, around 14-15℃. The only thing that is giving us chills is the perspective of actually getting out.

The further we go, the more puddles appear. I clumsily try to avoid them but Pierre just scoffs. "You can jump all you want but sooner or later you’ll get wet." Soon the water reaches my ankles. Then my calves. And finally my knees. Our guide is not impressed: "There are places in the 14th arrondissement where the water goes up to your neck. You can go swim there." Despite the wet clothes, we aren’t particularly cold. In the catacombs, the temperature stays more or less stable throughout the year, around 14-15℃. The only thing that is giving us chills is the perspective of actually getting out.

It’s a weekday, so the catacombs aren’t very crowded. But we aren’t alone. Our guide asks one of the passing groups about the situation at "the beach." A young boy from the other group, with a speaker in his backpack, says it is empty - we’ll get to be alone there. Fifteen minutes later we arrive at our destination. The vast room, called "the beach" because of its sandy floor, allows you to stretch out and fully breath in. The walls are full of different forms of art of varying quality. Not just graffiti - the entrance to the beach is guarded by a golem-like sculpture, while mannequin’s hands protrude from the walls. Next to the beach you have "the Cinema" - a room in which actual screenings used to take place, the electricity cabled down through an open manhole. As a souvenir of those times, the walls are covered in graffiti connected to famous films and actors: Leon: The Professional, Charlie Chaplin, The Terminator, and Clint Eastwood.

Is there anything to be scared of?

As Pierre walks me to the exit of the catacombs, I ask him if he’s not scared of going down there, especially when he’s alone. "Nothing bad has ever happened to me in there," he replies. "These days you mostly encounter kids from good families rather than criminals." Of course, there are legends about Satanic "black masses" or fights between punks and skinheads back in the 80’s. But the stories are pretty far-fetched.

As Pierre walks me to the exit of the catacombs, I ask him if he’s not scared of going down there, especially when he’s alone. "Nothing bad has ever happened to me in there," he replies. "These days you mostly encounter kids from good families rather than criminals." Of course, there are legends about Satanic "black masses" or fights between punks and skinheads back in the 80’s. But the stories are pretty far-fetched.

These days, a special police squad has been established to maintain order in the catacombs. Locals call them the "catacops." But apparently their squad consists of just five members, which - considering the catacombs span some 200 kilometres - is insufficient to say the least. Therefore, a certain symbiosis has developed between the cataphiles and the catacops. "It’s also in [the police’s] interest to have a few people hanging out there, to prevent worse things than graffiti and parties happening," explains Pierre. But of course, tolerance has its limits. The (not very efficient) walling of entrances has been stopped, but you still risk a €60 fine by setting foot in the catacombs.

"Be careful, it’s going to get really narrow now." Pierre’s voice pulls me out of my thoughts. There is nothing to be scared of in the catacombs - as long as you’re not claustrophobic. The wall gets lower, forcing us to lean forward. Before I even realize what’s happening, we’re made to crawl. My camera bag and tripod begin to really get in the way. The tunnel makes a turn and starts leading downwards. Pierre passes me and goes a few meters ahead, which - in these circumstances - seems to me like an unreachable distance. Despite the low temperature I start to sweat. "I went legs first, but there’s no ideal way to do it!" Hearing Pierre’s voice ahead reassures me. Finally, we reach a higher corridor that leads us to the exit.

The city of shadows under the City of Lights

The Parisian underworld is a huge phenomenon. And so are its inhabitants. Sure, each city has its adventurers, urban explorers breaking into deserted houses and factories. But cataphiles are urban explorers on steroids. Although the catacombs cover only a small portion of Paris, they seem much larger. There is no metro or city bikes, people are not walking around with their head stuck in their phones. You cannot buy anything and your dirty clothes are not the sign of affiliation to any particular section of society. Even a short trip like this one can change your perspective on what is going on on the surface. No wonder so many want to get a firsthand experience. Or that those who manage to find a way in usually want to come back.

---

---

Voglio Vivere Così is a collection of eight stories that describe unique and alternative lifestyles. A sneak peek into a closed world. Eight stories for eight weeks, chosen by the cafébabel editorial team.

Translated from Po drugiej stronie Paryża. Półlegalna wyprawa do katakumb