Jorge Semprun: Buchenwald concentration camp survivor 65 years on

Published on

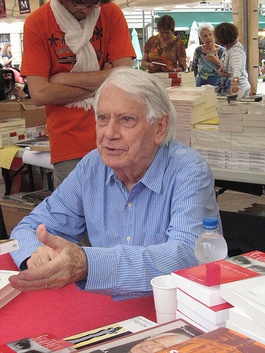

The Spanish former concentration camp inmate, politician and Oscar-winning writer, 86, was at the Paris book fair on 28 March to present his latest work, 'Europe from yesterday to today: a tomb cradled in clouds'. 11 April 2010 marks 65 years since the Nazi camp's liberation

It's been 65 years since the liberation of the Buchenwald concentration camp, which was created by the nazis and re-opened by the soviets. Jorge Semprun, a real citizen of the world, is both puzzled and lucid about the role that collective memory plays in the troubled history of Europe. Nor will you find resentment in the sometimes cheerful, sometimes thoughtful face of this European intellectual, or in his texts. The lectures that the 86-year-old gave between 1986 and 2005 to a young, interested and demanding public are compiled in his latest French-written work, (Une tombe au creux des nuages : Essais sur l'Europe d'hier et d'aujourd'hui, Broché). Speaking as a writer, Semprun looks back on an inconceivable European past. Speaking as a politician, he puts the future into perspective for new European generations.

It's been 65 years since the liberation of the Buchenwald concentration camp, which was created by the nazis and re-opened by the soviets. Jorge Semprun, a real citizen of the world, is both puzzled and lucid about the role that collective memory plays in the troubled history of Europe. Nor will you find resentment in the sometimes cheerful, sometimes thoughtful face of this European intellectual, or in his texts. The lectures that the 86-year-old gave between 1986 and 2005 to a young, interested and demanding public are compiled in his latest French-written work, (Une tombe au creux des nuages : Essais sur l'Europe d'hier et d'aujourd'hui, Broché). Speaking as a writer, Semprun looks back on an inconceivable European past. Speaking as a politician, he puts the future into perspective for new European generations.

Read also: Jorge Semprun and former French prime minister Dominique de Villepin on what it means to be European in a2006 interview

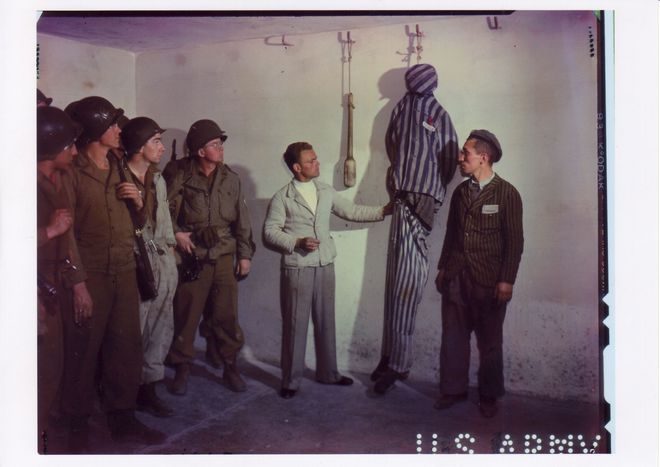

On 28 March, the author is an invitee of the France-Israel foundation at the Paris book fair. He remembers how, alongside other Buchenwald inmates, he was a 22-year-old communist resistant taking up arms and fighting to at last bring down the gates of hell on 11 April 1945. 'The irony of the story,' begins Semprun, 'is that the American GIs had beaten and dispersed the Buchenwald garrison and charged victoriously onto Weimar. But it was only five days later, on 16 April, when two soldiers, Egon W. Fleck and Edward A. Tenenbaum, who had stayed behind entered the camp alone - so effectively, Buchenwald concentration camp was only really freed by American Jews of German origin!' Situated only a stone’s throw from Weimar, the home of German poet Goethe, the Buchenwald camp chronicle did not stop with the nazi defeat.

Buchenwald: nazi camp becomes soviet gulag

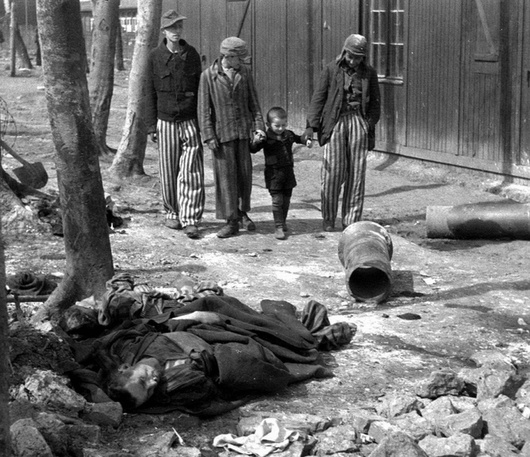

'In June 1945 the last inmates left the concentration camp,' Semprun says. 'But the soviet union re-opened the camp that following August for ex-nazis and any other resistors to the soviet regime.' 28, 455 prisoners, according to soviet records, were held in what became known as NKVD special camp number 2 up until January 1950. Harsh camp conditions, malnutrition and cold were such that 7113 died and were buried in mass graves. Until the fall of the soviet bloc, the only mention in the national memorial erected by the German communist government at Buchenwald is of the nazi concentration camp. Worse, other than the crematorium, the main gate and the two guard towers, the government ordered the camp's destruction and planted trees to hide the mass burial grounds of camp 2 victims. Today, not far from the forest where Goethe liked to walk, young Europeans who visit the camp with their history teachers can contemplate this artificial wood rooted in the Gulag burial grounds and try to understand the dual memory handed down from the 20th century.

'In June 1945 the last inmates left the concentration camp,' Semprun says. 'But the soviet union re-opened the camp that following August for ex-nazis and any other resistors to the soviet regime.' 28, 455 prisoners, according to soviet records, were held in what became known as NKVD special camp number 2 up until January 1950. Harsh camp conditions, malnutrition and cold were such that 7113 died and were buried in mass graves. Until the fall of the soviet bloc, the only mention in the national memorial erected by the German communist government at Buchenwald is of the nazi concentration camp. Worse, other than the crematorium, the main gate and the two guard towers, the government ordered the camp's destruction and planted trees to hide the mass burial grounds of camp 2 victims. Today, not far from the forest where Goethe liked to walk, young Europeans who visit the camp with their history teachers can contemplate this artificial wood rooted in the Gulag burial grounds and try to understand the dual memory handed down from the 20th century.

Germany, epicentre of evil ?

In his autobiography 'Literature or Life' (L’écriture ou la vie, 1994, Gallimard), Jorge Semprun describes spending his two years 'living without an identity' and seeing his body 'emaciated yet alive' in the camp. However, Semprun doesn't use Buchenwald to pile guilt on young Germans today, but widens his range of thought by citing the Romanian poet Paul Celan:

'Then as smoke will rise into the air/ Then a grave you will have in the clouds/ There one lies unconfined/ death is a master from Germany'

'I wondered if that verse was strictly true when I went back. Clearly not.' said Semprun upon receiving the peace prize of the German book trade (Friedenspreis des Deutschen Buchhandels) in 1994; his first return to Buchenwald was in March 1992. 'For French jews persecuted under the Vichy government, the 'master of death came from France',' Semprun explains. 'And (Russian journalist) Varlam Chalamov tells us that the 'master of death came from the soviet union'. Death is a master from the human race.' These words, first used before a German audience in the lectures that Semprun gave between 1986 and 2005, and repeated for the Paris book fair listeners in 2010, calls for a reconciliation between yesterday's and today's Europe, based on lucidity.

Remembrance: moral obligation

These words recall the permanent paradox of evil and humanity, of Buchenwald and its contradictory opposite, Weimar; the German capital of culture is situated only five miles away. 65 years after the opening of the camp for jews of German origin, Buchenwald remains at 'the heart of European memory', says Semprun. 'Only the German people can and should take into account the two totalitarian regimes of the twentieth century: nazism and stalinism.' But the Germans are not the only ones concerned. Back in 1995, Semprun said that 'the historical memory of the German people deeply concerns all Europeans.'

Since it opened in 1992, the Buchenwald memorial has offered educational courses on the nazi concentration camp experience and also a 'different way of apprehending Buchenwald's history from GDR times up until today.' This assures that history is looked at from all angles - not only the way it is recorded - so that its commemoration is not just a ritual excluding dialogue, as was the case under the soviet government. Historical vigilance remains essential if the Europe of today is threatened by the acceptance of its cultural diversity, rather than a fear of totalitarianism. 'The greatest danger for Europe is lassitude,' said Semprun at a conference held in Vienna in 1935, citing the philosopher German philosopher Edmund Husserl. Tired of Europe? I really don’t know what you mean…

Images: mai ©Ardean R. Miller/ Buchenwald memorial; Jorge Semprun ©Dinkley/ wikimedia; camp photo by ©Gérard Raphaël Algoet Sammlung Gedenkstätte Buchenwald; school trip to Buchenwald ©kaswenden/ Flickr

Translated from Jorge Semprún: Buchenwald, 65 ans après