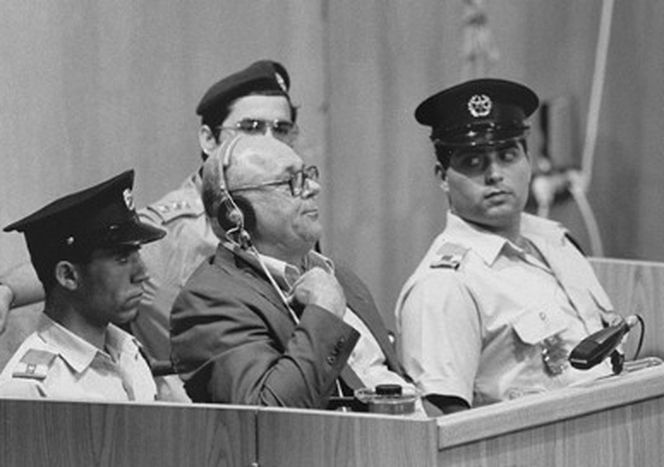

John Demjanjuk: one of Europe's last Nazis takes the stand

Published on

Translation by:

James FrisciaUndoubtedly one of the last acts of de-nazification in history has been playing out inside the appellate court of Munich since 2 December. International media is closely tracking the case against the accused, a former executioner at the Sobibor concentration camp.

Trial hearings have resumed after being halted due to the poor health conditions of the 89-year-old defendant and US extradite; we hear opinions from young people in Germany

Recruited by the SS to be a part of Trawniki, a generic term which refers to the guards recruited by the nazis in eastern Europe, the Ukrainian-born John Demjanjuk is now without nationality. Granted American citizenship after the war, when he moved to the US in 1951, Demjanjuk was stripped of this in May 2009. Demjanjuk needs to answer for his participation in the murder of over 27, 900 Jewish prisoners who were executed during the six months he was at the camp in 1943. This number is confirmed by identity cards and also by the testimonies that will be presented at the hearing.

Useful process?

This trial is momentous; Demjanjuk is one of the last nazis still alive who can be held accountable. Not only could the case be the last in the long and painful history of ‘de-nazification’ in Germany, it is also the first time that German courts will try a foreign nazi. Until now, only German nationals have been implicated in the events of the nazi era. Yet, fifty years after Germany began its often painful soul-searching process, does it make sense to confront an old man with his crimes?

This trial is momentous; Demjanjuk is one of the last nazis still alive who can be held accountable. Not only could the case be the last in the long and painful history of ‘de-nazification’ in Germany, it is also the first time that German courts will try a foreign nazi. Until now, only German nationals have been implicated in the events of the nazi era. Yet, fifty years after Germany began its often painful soul-searching process, does it make sense to confront an old man with his crimes?

‘He was a major figure who was responsible and he has blood on his hands,’ says Christine, a 26-year-old German student. ‘The matter is not up for debate, he should be tried. His actions must be punished, no matter how much time has passed,’ she added. Among youths, this opinion is widely shared and is not a cause for much controversy. However when the cultural consequences of a process like this are considered, such as what lessons it will offer future generations, opinions are more nuanced. ‘Of course it should be discussed,’ affirms 23-year-old Franz, ‘however the issue will never be completely clear. The most senior German officers have never been tried.’

This feeling that the process is not concluded is often accompanied by a certain fatalism, perfectly captured by Max, a 30-year-old professor of German: ‘While even some Nazi leaders still live, Nazism will not disappear from either our history or our present.’ More than reflection or investigation into the crimes committed during world world two, for many young Germans, it is time that their country definitively reconciles with its past.

(Images: Main of John Demjanju ©The Israeli Government Press Office- Sobidor/Jacques Lahitte CC/Wikimédia)

Translated from L’un des derniers nazis sur le banc des accusés en Allemagne