Jeremy Deller: the British artist who likes art, but can’t draw

Published on

The 42-year-old is ‘vaguely political’ and pretty vague. 2004's Turner prize winner talks unemployment, Britsh folk culture as 'real art' and pigeons in Paris

Bad things: Andrew crazy has issues with fat people. Torn between Stacey and I. Andrew married him. Sex question mark. All good things child house money. The sun’s out on the restaurant terrace of the Palais de Tokyo, the French capital's biggest space for contemporary art, and Jeremy Deller is reading extracts from a British daily aloud. ‘This is a great one, a to-do list,’ he says of the collection of notes that people find on the street. 'Convince myself I’m not madly in love with him.'

Palais de Folk-yo

The north Londoner has spent the summer preparing the second in a six-part series of exhibitions giving a carte blanche to a renowned artist. Backstage at 'From One Revolution to Another', it’s like entering a fair. Acres of space beckons you round to larger spaces featuring French rock and Soviet electro. British trade union banners blaze from the ceiling above, whilst technicians knick-knack on various structures below.

The north Londoner has spent the summer preparing the second in a six-part series of exhibitions giving a carte blanche to a renowned artist. Backstage at 'From One Revolution to Another', it’s like entering a fair. Acres of space beckons you round to larger spaces featuring French rock and Soviet electro. British trade union banners blaze from the ceiling above, whilst technicians knick-knack on various structures below.

Even if reviews are good, I don’t like hearing about it

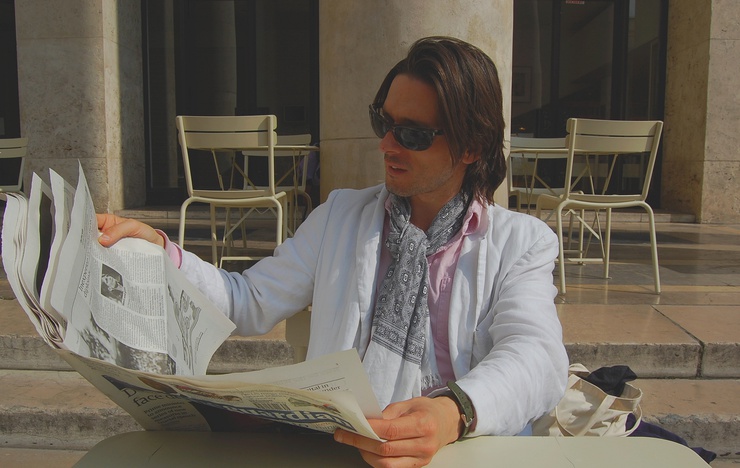

‘There’s no massive theme to the show,’ the former art history student explains outside, wearing shades, a white blazer, his bright yellow socks encased in open-strapped sandals. ‘It’s whatever I could find at the time. When I first visited I was overwhelmed by how big it was, it scared me somewhat. The acoustics might be odd,’ he pauses. You manage your first carte blanche curatorship, the 42-year-old shrugs, by just ‘getting on with it really. You have an idea and see how far you can push it. It’s important to show things that haven’t been seen,' he adds, of his interest in the Russians’ love of electronic music. He is averse to reviews in general; the exhibition opens in two days. 'This could be received really badly! You do the best you can and think about the next thing. Even if reviews are good, I don’t like hearing about it, I don’t like photos of myself or being on film or hearing my voice. It’s slightly embarrassing isn’t it - do u know what I mean.'

We ‘talk aimlessly’, as Deller jests at one point, going over the ‘not that much' that he has done since winning the Turner Prize, Britain’s very publicised contemporary art award, in 2004. ‘The British folk and vernacular art that we’re repeating for this exhibition,’ he explains, ‘is not museum-based, but focuses on people who are creative in everyday life. It’s about hobbies, public performances, everything that happens outside a gallery with an artistic nature to it - cake decorating, tea competitions, demonstrations, I’ve always liked them.’ Can a French eye fully appreciate images celebrating England’s gurning competitions? ‘They just don’t appreciate it or see it here,’ Deller guesses. ‘I bet everything happens in France in some sort of way, costumes and dances and stuff.’

'Vaguely political'

A torrent of wings interrupt us as an invasion of pigeons land on the freshly vacated table beside us to peck at forks and leftovers. We surpass the Hitchcock moment and return to the post-Turner moment. ‘Its great, a brilliant thing to win. It didn’t change me,’ he counters. ‘If you’re down to earth anyway it doesn’t really matter. It changes maybe how people react towards you, but that’s just funny. My friend Alan (Kane) would never let me become all pretentious,’ he says. (With the British artist, he created the 30 foot Greasy Pole in Egremont in 1999). It's true that much of what Deller is noted for was done around 'Turner time'. During the European elections in 2004, his Manifesta 5: Parade enactment in Saint Sebastian with Spanish and Basque locals reflected on ‘things going on in their lives’. He hopes to do a second instalment next year in Britain; coincidentally, just before the next European elections in June. ‘I wasn’t even aware of that,’ he remarks. ‘It doesn’t really excite British or French people that much.’

His political motivations are the same as everyone else, he claims. ‘British art in the nineties was depoliticised on the whole, and I can’t remember who I voted for in May’s mayoral elections - but it was a protest vote against Boris Johnson.’ He agrees that the previous winners of the prize were less politicised; his entry was a multimedia installation of a docu-journey through Bush’s Texas. ‘Brits are more aware than they would be in America,’ he says, where he spent a year teaching in San Francisco. ‘They’re quite well informed of the world situation in Britain, but the media there is terrible. My work doesn’t help it make more aware, I don’t take any credit for that.’

His political motivations are the same as everyone else, he claims. ‘British art in the nineties was depoliticised on the whole, and I can’t remember who I voted for in May’s mayoral elections - but it was a protest vote against Boris Johnson.’ He agrees that the previous winners of the prize were less politicised; his entry was a multimedia installation of a docu-journey through Bush’s Texas. ‘Brits are more aware than they would be in America,’ he says, where he spent a year teaching in San Francisco. ‘They’re quite well informed of the world situation in Britain, but the media there is terrible. My work doesn’t help it make more aware, I don’t take any credit for that.’

Luckily, there’s this thing called conceptual art, where you don’t have to draw perfectly to become an artist

He doesn’t teach in Britain because it is too time-consuming, British and bureaucratic. ‘Not really my world. I like music, but I can’t play an instrument. I like art, but I can’t draw,’ Deller says laughingly. 'Luckily, there’s this thing called conceptual art, where you don’t have to draw perfectly to become an artist. I’m just lucky. Anyone can make a name for themselves initially. It’s how you extend that into something resembling what you could call a career.’ His now-retired parents tried to help him find a direction through years of unemployment, ‘with very little success. When I left college it was ok to be unemployed because you weren’t the only person. I wasted a lot of time. That’s probably why I’m trying to make up for it now by trying to do everything I can, over-working.’ It’s a different era now, he recognises. 'There are more computers, art students, colleges and seem to be more galleries.’ But he won’t advise budding artists in a similar scratch, for fear of sounding 'like some sort of motivational speaker.'

Catch the exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo, 13 avenue du Président Wilson, 75116 Paris, and a procession along the Deansgate mile 'that promises to show Greater Manchester in all its glory' at the Manchester International Festival 2009 (2-19 July 2009)