Jean-Christophe Bas: 'the erasmus generation doesn’t know how lucky it is'

Published on

Translation by:

Helen SwainFinally, on 9 November 1989, there was peace. Young Europeans born after this historic day did experience the war. But what does the construction of Europe mean to them? In his book L’Europe à la carte, Jean-Christophe Bas calls upon the spoiled children of the eurogeneration’s in order to create a less self-centred Europe.

'I’m not very far from Paris – I can meet you tomorrow!' Calling me from Bosnia, 50-year-old Jean-Christophe Bas demonstrates yet again that he is a citizen of the world. His work – first at the World Bank and then at the UN, where he is now director of the partners in the alliance of civilisations – means that he is constantly exploring the four corners of the world. Indeed, on 5 November the publisher Le Cherche Midi will be publishing his new book about Europe – a collection of maps of Europe and of texts by well-known personalities. As his grandfather was involved in initiating the first Franco-German exchange of deputies after the second world war, in 1950, it seems that Europe is a family passion.

'I’m not very far from Paris – I can meet you tomorrow!' Calling me from Bosnia, 50-year-old Jean-Christophe Bas demonstrates yet again that he is a citizen of the world. His work – first at the World Bank and then at the UN, where he is now director of the partners in the alliance of civilisations – means that he is constantly exploring the four corners of the world. Indeed, on 5 November the publisher Le Cherche Midi will be publishing his new book about Europe – a collection of maps of Europe and of texts by well-known personalities. As his grandfather was involved in initiating the first Franco-German exchange of deputies after the second world war, in 1950, it seems that Europe is a family passion.

Why did you write L’Europe à la carte?

This book is dedicated to my children, who are 15 and 16, and to the erasmus generation, who were born after the fall of the Berlin wall. This generation’s idea of what established Europe after the war is limited to peace and reconciliation. It is necessary now to find a new project that can make them enthusiastic about Europe. We cannot continue to mobilise about peace, which the new generation takes for granted and considers to be obvious, even if it is important to say again and again that maintaining a climate of peace should never be taken for granted and must be worked at every day. I am working a lot at the moment in the Balkan region, and I can say without being too inaccurate that, if there were not the perspective of joining the European Union, the region would be completely undermined by conflict. What is fantastic about the European project is that ancestral quarrels about local borders, neighbourhoods and ethnicities are diluted in the mass of Europe without any loss of identity.

L’Europe à la carte lists 67 maps of Europe. Why?

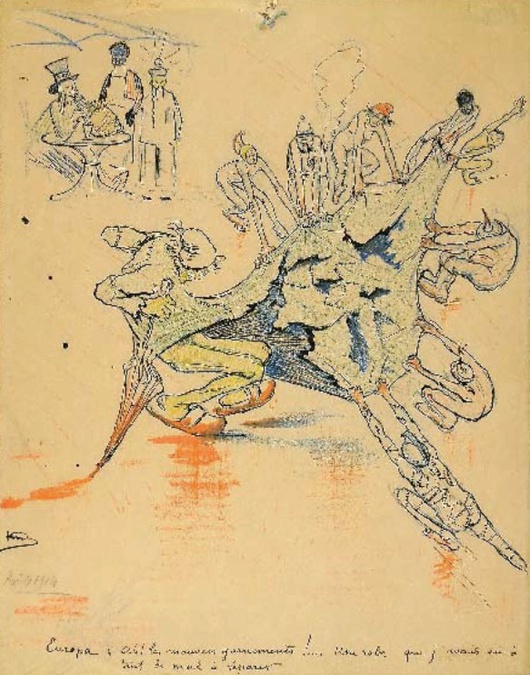

In the spring of 1989, I began to collect maps and caricatures of Europe. The book opens with my first acquisition: a map from August 1914 (featured here), which was only three weeks before the beginning of the great war. When I began working at the World Bank ten years ago, I covered my office wall with maps, and these regularly attracted my visitors’ attention. I deduced from this that people can become passionate about Europe in this way. Alongside the maps, the book features writings from 68 well-known personalities from all horizons. When a project loses its passion, you have to come back to its essence. That is why Ban Ki Moon, Daniel Barenboim, Amin Malouf and Inès Sastre answer the question of what constitutes their vision of Europe.

In the spring of 1989, I began to collect maps and caricatures of Europe. The book opens with my first acquisition: a map from August 1914 (featured here), which was only three weeks before the beginning of the great war. When I began working at the World Bank ten years ago, I covered my office wall with maps, and these regularly attracted my visitors’ attention. I deduced from this that people can become passionate about Europe in this way. Alongside the maps, the book features writings from 68 well-known personalities from all horizons. When a project loses its passion, you have to come back to its essence. That is why Ban Ki Moon, Daniel Barenboim, Amin Malouf and Inès Sastre answer the question of what constitutes their vision of Europe.

The book is published on 5 November in France. Why now?

First of all because it is the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin wall, which led to a re-establishment of the European pact, given that the 1950’s was linked to the cold war, and that, along with the wall, it fell apart.

Is there a chance that it will succeed?

The rejection of the constitution [by referendum in France and the Netherlands in 2005 - ed] wounded me. One day, historians will see this moment as one of absolute blindness. It’s fashionable to accuse Europe of all evils, but nevertheless, it was this seized-up Europe that succeeded in establishing the euro; it was this 'sieve-like' Europe that created the Schengen agreement [for free movement of persons across borders - ed]; it was this powerless Europe that is now the primary backer of the developing countries and that is the most involved in solving the global warming problem. There is a paradox if we believe in a lack of interest for the European cause. I think there is an incapacity to communicate on this project. For a while, I thought of calling my book At the Bedside of a Hypochondriac Europe, because it is so true that Europeans are constantly complaining about their situation and considering themselves to be the victims of all sorts of ills, yet Europe remains extraordinarily modern and vital.

Nevertheless, the Irish have just (re)voted massively in favour of the Lisbon treaty, which will replace the former constitution…

I would like to hope that an institutional dynamic will be relaunched, but it is not sufficient! For the past 15-20 years, we have lost ourselves in discussions about details and have forgotten about the bigger picture. In fact, I don’t think anyone in the book mentioned the institutional debate.

Is that a coincidence?

It’s not a coincidence if we consider that I asked seventy authors to give their personal vision of Europe. Nobody, apart from a bureaucrat, perhaps – and I am one! – would get enthusiastic about an institutional construction.

If the generation of the founding fathers built Europe for peace, what do you think is the role of the erasmus generation?

Personally, I am struck by the fact that Europe has forgotten its universal vocation. The wonderful thing about Europe is that it represents a model of society for the rest of the world in which, as Jacques Delors used to say, 'competitiveness stimulates, cooperation reinforces and solidarity unites'. The project for the erasmus generation should be to free themselves from the idea of a self-centred Europe. All the regions of the world with which I have worked look at Europe with admiration and envy. In L’Europe à la carte, 30 texts were written by non-Europeans. For example, Ban Ki Moon, the secretary general of the United Nations, has called upon Asia to develop its regional integration along the same model as the European Union. This book reminds the members of the erasmus generation that they are spoiled children who do not know how lucky they are to live in one of the only areas in the world where there is prosperity, peace, stability and solidarity.

Discover a selection of texts from L’Europe à la carte on the book’s blog

Translated from Jean-Christophe Bas : « La génération Erasmus ignore sa chance »