Jackie Kay: telling the difference between heart attacks and orgasms

Published on

Novelist, poet and short story writer Jackie Kay is one of the more distinctive voices on the British literary scene. Her writing is both poignant and hilarious and her reading at the Edinburgh international book festival reflected this. Later on in the festival, we grab a cup of tea together and talk about politics and pigeonholes

I bumped into Jackie at a reading by Jeanette Winterson. Both writers were adopted as babies and have traced their respective searches for their biological parents in recent autobiographies. Winterson argues that as an adopted child you have an unusual approach to narrative: you are placed in a story after it has already begun. When we discuss this later, Jackie is sceptical, arguing that, ‘It’s not so much that you come with something missing, as Winterson was implying. When you’re adopted, you come into a story, you’re born into a story and you’re given that story.’ Her voice warms as she starts to talk about her adoptive parents. ‘I don’t feel like I was born with something missing because my mum, my adoptive mum, told me the story. I do feel very strongly that she passed the story down and that the story for us became something like DNA. Instead of inheriting her nose or her eyes, I inherited her sense of humour, her love of language and her love of story. In the debate of nurture versus nature it seems to me that stories are as important as DNA, as random genes sharing.’

At her reading, Jackie had talked about the importance of empathy to a writer and touched on the idea of empathy being political. I ask whether she thinks that writing is in its very nature political. ‘Yes,’ she replies with certainty. ‘We deal as writers with the world that we live in, even when we think we’re not. Our interpretation of what’s political and of what we want our readers to think about is wide open. I would never want to tell my readers how to think or what opinions to have. I wouldn’t want to be polemical; I wouldn’t want to be didactic or dogmatic or bossy.’ She laughs at this point, and I wonder if she is accused of being bossy outside of her writing. ‘However, I would want to be provocative,’ she continues. ‘I want people to think, and I do think I am political, definitely.’

At her reading, Jackie had talked about the importance of empathy to a writer and touched on the idea of empathy being political. I ask whether she thinks that writing is in its very nature political. ‘Yes,’ she replies with certainty. ‘We deal as writers with the world that we live in, even when we think we’re not. Our interpretation of what’s political and of what we want our readers to think about is wide open. I would never want to tell my readers how to think or what opinions to have. I wouldn’t want to be polemical; I wouldn’t want to be didactic or dogmatic or bossy.’ She laughs at this point, and I wonder if she is accused of being bossy outside of her writing. ‘However, I would want to be provocative,’ she continues. ‘I want people to think, and I do think I am political, definitely.’

Jackie in the box

There was once a theory that there could be no female Scottish poets, because a Scottish poet is already ‘other’. In case anyone still holds this theory, it should be well and truly shattered by Jackie. In a society where the default is white, ‘posh, grown-up, male, English and dead’ (‘Kidspoem/Bairnsang’, Liz Lochhead), the 51-year-old writer could almost define otherness, fitting neatly into the pigeonholes of black, lesbian, female and Scottish.

Or not so neatly. ‘I think of myself as Jack-in-the-box,’ she giggles. ‘I’m Jackie in the box, you know. People put me in boxes all the time but I jump back out.’ More seriously, she explains, ‘I don’t mind being defined. I mind when people think that those definitions therefore define your writing. I don’t mind someone saying I’m black – I am black. I don’t mind someone saying I’m Scottish – I am Scottish. I don’t mind someone saying I’m a lesbian, but I do mind if someone says, ‘this is you, you’re a lesbian writer.’ There’s no such thing as a lesbian writer!’ Jackie is softly spoken, but her voice acquires an edge as she becomes passionate. ‘Those kinds of questions don’t get asked of white writers. Twenty years ago when crimes were reported, they would only describe someone if they were black. Now with there being so many different cultures here, they do actually define white. In literature we need to catch up with journalism in that sense. Whiteness needs a definition too; it’s not just blackness. The same goes for heterosexuality.’

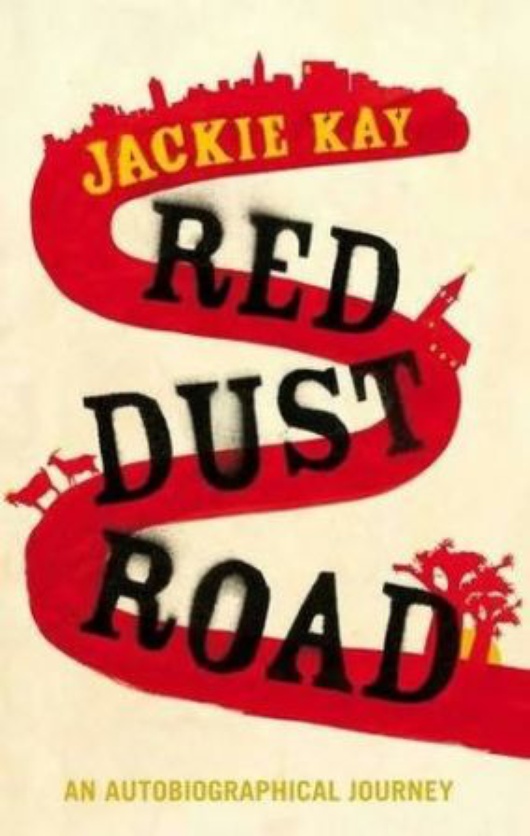

Jackie Kay's autobiography 'Red dust road'

Jackie Kay's autobiography 'Red dust road'

I pause to let Jackie drink her tea. She speaks quickly and towards the end of every sentence starts to raise her cup to her lips, only to have another idea and continue talking. ‘I think there is a connection between being an outsider in some way and being a writer,’ she muses. ‘I think that most writers feel outside in some way, even if they’re people that we think of as inside.’

'Old people and orgasms'

Her latest collection of short stories ‘Reality, reality’ focusses on people who are in one way or another on the edges of society and she had read from the collection at the book festival. ‘Mini me’, the diary of a woman trying (and failing) to start dieting, was met with noisy nods of assent from the female contingent of the audience. Another tale 'These are not my clothes' is narrated by an elderly woman in a care home and lead Jackie into a passionate diatribe against our culture’s treatment of older people. ‘I think it’s awful the way that old people are stereotyped nowadays,’ she exclaimed. ‘As if they never marched against apartheid, as if they never brought us up, as if they’ve never read the entire works of Joyce in one week.’ There was a smattering of applause as she paused for breath.

The writer’s passionate outburst provoked an unexpected response. When the time came for questions, an elderly gentleman in a tweed jacket put up his hand. ‘Jackie,’ he began, ‘you’ve talked a lot about old people and orgasms.’ Unsurprisingly there was a slight stir in the audience before he continued. ‘For years, I taught a course about aging for beginners. The main thing we had to teach participants was how to tell the difference between a heart attack and an orgasm.’

Image: Jackie Kay © Trevor Fountain