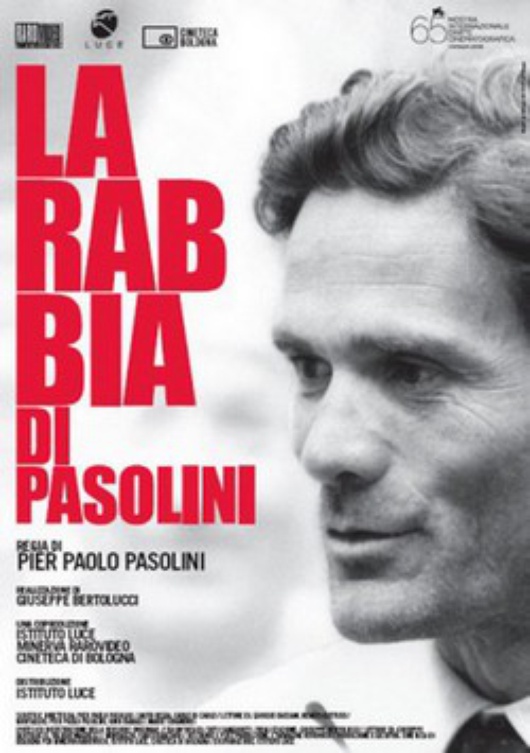

Italian poet Pasolini, rage and Sarajevo

Published on

Translation by:

Helen SwainSometime between 1 - 2 November 1975, Pier Paolo Pasolini was killed. He became a vehicle for peace messages during the Poetry International Festival held in Sarajevo from 3 - 5 October 2008

One hundred pages of poetry in Bosnia weigh as much as a kilogram of gold; and foreign poets are spoiled in the windows of Sarajevo's bookshops. According to Marsala Tita's parallel, in Sarajevo, when you stir the air as you walk and pass palaces that are still riddled with bullets, you can feel the smut of history raining down on you. Pier Paolo Pasolini wrote, 'What happened to the world after the War and the War's aftermath? Normality! In a state of normality, without the excitation and the strong emotions of the War years, one does not look around. Man tends to fall asleep in the state of normality; he forgets how to think, to judge, to ask himself who he is. This is when the state of emergency is discovered and artificially created by poets – poets, those ever-indignant champions of intellectual rage and philosophical fury.'

One hundred pages of poetry in Bosnia weigh as much as a kilogram of gold; and foreign poets are spoiled in the windows of Sarajevo's bookshops. According to Marsala Tita's parallel, in Sarajevo, when you stir the air as you walk and pass palaces that are still riddled with bullets, you can feel the smut of history raining down on you. Pier Paolo Pasolini wrote, 'What happened to the world after the War and the War's aftermath? Normality! In a state of normality, without the excitation and the strong emotions of the War years, one does not look around. Man tends to fall asleep in the state of normality; he forgets how to think, to judge, to ask himself who he is. This is when the state of emergency is discovered and artificially created by poets – poets, those ever-indignant champions of intellectual rage and philosophical fury.'

Sarajevo remembered Pasolini in October through those same poets, both Bosniac and foreign. Today, there is no other city for Pasolini's Rage (a text which should have become a film); no other place is capable of illustrating its necessity. The intellectual indignation of his poetry has found its raison d'être in Sarajevo, particularly given that the verses' 'rage' has not been taken up, and that post-war 'normality' is only a suspended type of reality.

The Sarajevo between the ruins

To reach the Kino Teatar 'Bosna' – where the authors have begun by watching Pier Paolo Pasolini's short films and have had readings – one must cross the centre of the capital. It is like travelling a mini version of the road from the coast of Croatia at Dubrovnik to the interior of this ex-Yugoslavian country. From Mostar, battle-weary houses now hold up new dwellings, or perhaps it is the post-war constructions that lean on the ruins of memory; and in private gardens between the buildings, one can discover unexpected little cemeteries between the trees. With its mainly administrative and commercial new facades, the Milijacka part of Sarajevo hides an entire city that is still in ruins, squeezed in between two main streets. The first, the Marsala, has a western flavour to it, while the second, the Obala Kulina Bana, which runs along the river, is historical and mystical – it was under one of the bridges here, 'Attack Bridge', that the Archduke Ferdinand was assassinated. All around are more or less recent mosques, which are under construction.

‘Poetry is the only literary genre still able to generate real dialogue between cultures, between the east and the west. The main thing that hits me about Sarajevo is when I see the minarets and the European palaces and the mix of human faces between them,’ says Italian poet Giuseppe Conte as he walks, scrutinising partly his surroundings and partly his shoes. The faces of which Conte speaks are those of women wrapped in coloured pashminas, girls in miniskirts and stiletto heels, be-suited men and pedlars with Turkish features, all intermingled. In front of the great Ferhadija Orthodox cathedral, students meet up after their afternoon classes. From the Gazi Husrev Beg Mosque, megaphones carry the voices of the muezzin calling Muslims to prayer. People sit in cafes sipping coca colas and taking off their jackets after a day in the office; the way of life predicted by Pasolini in La Ricotta (1963), The Earth Seen from the Moon (1966) and What are the Clouds (1967).

During the projections – the films are subtitled in Bosnian – Francis Combes (a French intellectual poet who writes about the underprivileged classes) thinks for a moment and finally lets out one single sentence. ‘Amazing! Raw, realistic and violent.’ He laughs at Welles' remark in La Ricotta about the Italian bourgeoisie being the most ignorant in Europe. At the back of the very small room, Uruguayan writer and poet Rafael Courtoisie speaks of Pier Paolo Pasolini in his South American Spanish: ‘A man of deep-seated passions, a crazy man.’ After the closing credits, the video projector resumes. Italo-Croat Giacomo Scotti concludes: ‘At the end of a conflict, it becomes the task of men of culture, like Pasolini, to re-establish the broken connections between people.’

The street back to the Astra Hotel Ganj – where the poets are staying –offers another image of Sarajevo. The lights from the bookshops on the Marsala are still on, illuminating the shop windows; set between Pamuk and Coelho is Izet Sarajlic, the Bosnian poet who wrote People are Happy When Verses Meet. As we pass under an electoral manifesto, Almir Kolar, a young poet, shows me the face of a bald man with a serious expression. ‘That is Abdullah, a famous poet who is a candidate for the communal elections. He is centrist, Muslim and nationalist.’ He is also said to be pro-Europe. Pier Paolo Pasolini ended The Rage by announcing that the alternative to world violence and bloodshed and the only guarantee of real, lasting peace was the ‘smile of the astronaut’ indicating the way of the cosmos. Sarajevo, with its poems and poets, is gambles yet on earthly ways.

Translated from Pasolini visto dalla terra: La Rabbia a Sarajevo