Islands: some drops of Europe in the ocean

Published on

Translation by:

Joss CornerIslands and archipelagos, Antarctic territories, lively societies and cultures across the equator. The regions at the far reaches of the EU are attached to the continent by legal texts. But identity is not defined on the basis of decree

The French overseas territories, primarily Guadeloupe, then Martinique and the Reunion island, were paralysed by general strikes at the beginning of 2009. The symptom: a life on the French islands of the Antilles or Indian Ocean which is too expensive. But the economic difficulties double as a social malaise. ‘The effects are felt above all on the job market, on the level of professional integration. Guadeloupians looking for employment suffer from discrimination during recruitment,’ notes Élie Domota, secretary-general of the general union of the workers of Guadeloupe ('l’Union général des travailleurs guadeloupéens'), one example cited by the newspaper l’Humanité ('Humanity') on 9 February 2009.The target: a French state and politicians who ‘have allowed neither development nor the fight against unemployment.’

People sometimes don’t consider us as Europeans because they don’t consider us as wholly French in the first place

‘The protests on the islands are the result of a feeling of not being listened to enough or taken into account in the decisions made in metropolitan France, and by extension, on a European level.’ Auriane Audolant lives in France and grew up in Reunion Island, where the call for strike action was made on 5 March 2009. If we question her about her feelings on being a part of Europe, her response is half-hearted: 'We have the euro as currency too,' she observes. 'We’re represented on a European level. For example, the French Overseas MEP, Margie Sudre, is a well-known politician in Reunion Island.' Yet she maintains that 'the people of Reunion Island sometimes get the impression that they are a bit forgotten or not taken enough into account. The fact that we are part of the European Union whilst being geographically situated in the Indian Ocean means people sometimes don’t consider us as Europeans because they don’t consider us as wholly French in the first place. The difficulties that we encounter on a European level already exist on a national level.'

Treaties and the reality

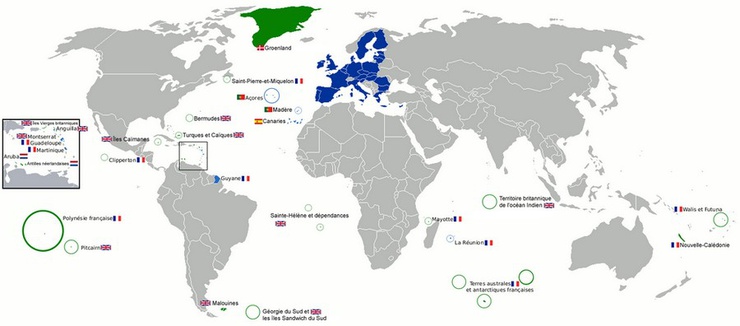

To what extent are these parts of Europe situated in the other hemisphere governed by Europe? There are three categories of overseas territories. Firstly the special member state territories ('régions ultrapériphériques', RUP), which are ‘wholly part of the EU and where the law of the European Union is fully applicable.’ These are notably the fewest in number. Among them we find the island chain of the Azores and Madeira, which are Portuguese, the Canaries (Spain) and the French overseas departments (including Guyana). Next come the overseas countries and territories which are governed under their own system and do not form an integral part of the EU ‘but benefit from a privileged relationship with the EU’. Among the 21, we find, for example Danish Greenland and the English Cayman Islands. Their inhabitants are free to circulate in European Union and the markets are open to them, as is the culture.

'Our feeling of belonging to Europe is refracted through the prism that is the French state'

At home, the cultural mix is original. 'Our roots are diverse and varied, African, American-Indian or Asian,' comments Jean-Claude Dellon, originally from Guadeloupe. So why not European? ‘We are French before anything else, and France is a part of Europe. We benefit from the latter, our feeling of belonging to Europe is refracted through the prism that is the French state,’ he continues. How can we reinforce these links, these exchanges whilst still respecting the identity and the regional characteristics of the inhabitants of these territories?

Translated from Quelques gouttes d’Europe outre-mer