Is the EU an exclusive Christian club?

Published on

The European Union, though secular, is essentially an association of Christian countries. Would the addition of Turkey and its large Muslim population will better reflect the changing demography of the EU?

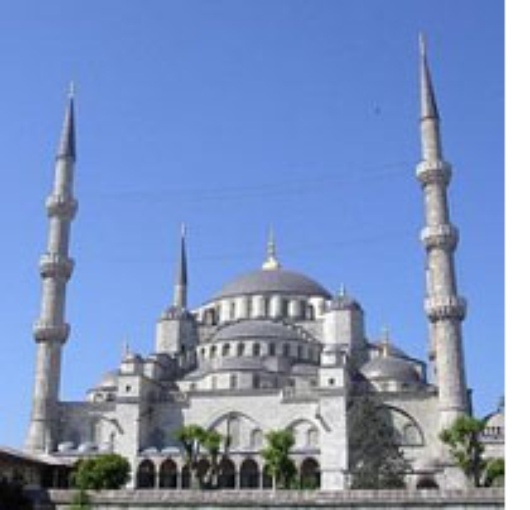

On October 6th the Commission reports on whether Turkey is ready to begin accession negotiations. Should Turkey eventually join the European Union, Brussels will be welcoming yet another secular democracy. However, the addition of over seventy million citizens, of whom 98% are Muslims, would also significantly alter the religious dynamic of the Union. Would this establishment of an ‘official’ Muslim voice in the EU usher a greater sense of tolerance and understanding of the Muslim faith in what has traditionally been a Christian Union?

On October 6th the Commission reports on whether Turkey is ready to begin accession negotiations. Should Turkey eventually join the European Union, Brussels will be welcoming yet another secular democracy. However, the addition of over seventy million citizens, of whom 98% are Muslims, would also significantly alter the religious dynamic of the Union. Would this establishment of an ‘official’ Muslim voice in the EU usher a greater sense of tolerance and understanding of the Muslim faith in what has traditionally been a Christian Union?

A Christian Union

Religion and European integration have always been inextricably linked – indeed many of the European Community's founding fathers, such as Adenauer and De Gasperi, were devout Roman Catholics. During wartime the former sought refuge in a monastery while the latter, pursued by Mussolini, fled to the Vatican, where he worked as a librarian until the Liberation. In fact, it could be argued that the entire notion of supranationality, the supremacy of a central authority over competing individual interests upon which the European model is based, is analogous with the structure of the Catholic Church. The issue of Christianity and the EU remains to this day, and can be seen in Gisard D’Estaing’s lobbying for explicit references to the faith in the draft EU Constitution.

It could therefore be suggested that the inclusion of Turkey, a Muslim state, would be an affront to the very cultural base upon which the EU has been constructed. Such a thesis, however, does not realistically stand up to scrutiny. Far from being an Islamic Republic, like Iran, for example, Turkey is a secular democracy and has been so since the creation of the Republic of Turkey in 1923. Paris or Vienna may cite cultural inconsistencies that make Ankara unsuitable for membership, but recent events suggest that ‘Old’ Europe and Turkey are closer than is commonly perceived. An example of this is the recent decision made by the European Court of Human Rights in the case of Leyla Sahin v. Turkey (application no. 44744/98), where it was held that the Turkish state was entitled to outlaw the wearing of Islamic headscarves in its Universities and Academic Institutions – a decision that mirrors recent legislation passed in France on the banning of religious symbols in state schools. Surely this bodes well for Turkish EU membership. It shows that even when dealing with highly charged religious matters, a traditionally Christian and a traditionally Muslim country, so often seen as the anti-thesis of one another, can be compatible regarding policy.

A Muslim voice in the EU

Perhaps the overriding benefit of Turkish EU membership would be that it would cultivate an official Muslim voice and identity in the Union. During the last half century, the end of colonialism and the benefits of economic migration to the West have brought about a significant shift in the ethnicity and religious denomination of EU citizens. Yet the leaders who negotiate legislation and ultimately determine the position taken by the Union are still predominately white Christian men. Rhetoric from Brussels constantly emphasises the importance of the citizen, yet the Council of Ministers is far from representative of the multi-culturalism in today’s expanding Union.

Accession as the way forward

Probably the greatest benefit of a predominately Muslim nation joining the EU is that it would challenge the wave of islamophobia invoked by the terrorist attacks three years ago in the United States, and would portray Islam as a peaceful religion, helping to illustrate the positives in Islamic culture and alienating and marginalising extremist movements that seek to destroy democracy. Prejudice is ultimately born out of ignorance, and an EU inclusive of the Turks would be an excellent first step towards challenging people’s preconceptions. The European Union also appears keen to assert its influence on wider global issues such as Israeli incursions in the West Bank. Surely this would carry more moral force if protocols were put forward by an organisation explicitly inclusive of Muslim culture and religion. A greater recognition of the Muslim population of Europe would also assist in the integration of candidate countries such as Bulgaria and Romania which have higher percentages of Muslim citizens than the current average in the EU of twenty-five.

Although any Turkish accession is many years away and dependent on Ankara meeting the Copenhagen criteria, an EU including Turkey would surely be a positive thing for the rest of Europe, as it would epitomise today’s multi-denominational Union and reflect how its religious makeup has altered over recent generations. Furthermore, it would enhance understanding and tolerance of Islam in Europe and create a political mechanism in the EU that better reflects the different cultures that constitute it.