Irish elections: expats can't vote on 25 February 2011

Published on

The Dail is dissolved! Irish citizens will be electing a new government to oversee recovery from the worst economic crisis in the state's history. However, many of them forced to leave by the four-year-old fianna fáil-green government's malfeasance will be denied a ballot

Ireland remains one of the holdout countries in granting its overseas residents a vote. The common refrain from those who agree with disenfranchisement is 'no representation without taxation.' This rings hollow for the thousands who’ve left Ireland since the crisis hit and who were paying tax up to a few months ago. Dublin think-tank the economic and social research institute (ESRI) estimates that 1, 000 people are emigrating weekly, a massive number for a country with a population of some 4.4 million. With an electorate of a little over three million, there are reasonable concerns that the one million overseas voters could skewer the results.

The privilege for Irish citizens abroad to vote in national elections is reserved for diplomats and army or police personnel on official duty overseas. As it stands, some twenty-nine of thirty-three council of Europe member states allow non-resident citizens to vote. Globally, more than 110 states grant it, including Botswana, Colombia, Indonesia, Iraq, Mali, Mexico and the United States.

Irish abroad: let me vote!

It rankles those who’ve left recently that their voices won’t be heard in the 25 February poll. 'My entire focus will be on the outcome rather than the taking part,' says Orlaith Finnegan, who worked as a PR consultant in Dublin before moving to Paris in 2010 where she is now an English trainer. 'The right to vote should be extended to Irish citizens abroad for up to five years after they've left either by a postal vote or facilitated through the embassy.' At the very least, Ms. Finnegan says a system of reciprocity should be in place so EU citizens can have say in who governs them if they’re living in another member state. 'In that case I would be perfectly happy to sit this one out and wait for the French presidential election in 2012.'

'I would be perfectly happy to sit this one out and wait for the French presidential election in 2012'

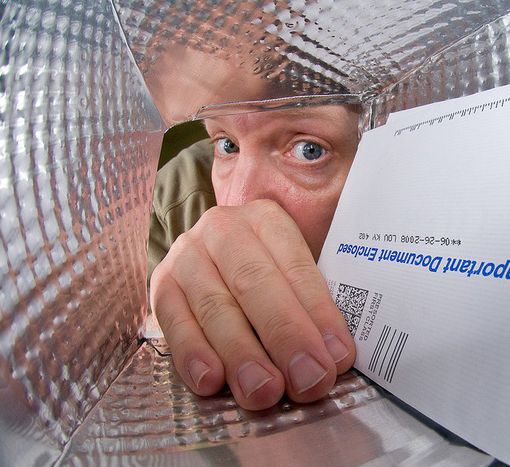

Journalist Vincent Murphy is expecting the delivery of his polling card at his old address in Dublin any day. But absent a means to vote from New York where he lives, the alternative is 'to fly home, collect that polling card and cast a vote. But that's not very realistic, is it?' Given the country’s history of emigration, he wonders why the debate on Irish voting rights for citizens abroad has never been addressed. 'My decision to move was personal. I can only imagine how much those who were forced to move overseas to look for work must want to give their verdict on the government.' He acknowledges that the sheer number of Irish people living abroad is not impossible to legislate for. 'Some way could be found to offer recent emigrants a vote - maybe if you lived in Ireland during the past two years. Other countries can do it. I do feel disenfranchised by not being able to vote. I intend moving home in 2012, and so the outcome of the election will have a material impact on my life.'

Catherine Flynn booked her flight from London as soon as it looked likely that the election would be on 25 February. 'I feel responsible for having voted the fianna fáil (of prime minister Brian Cown - ed) and the greens (junior coalition partner) into power,' explains the social media agency employee. 'The elections will shape the sort of Ireland I come back to.' IT consultant David O’Connell, who has lived in New York for a decade, finds it a 'disgrace' that there’s no facility for overseas voting but cautions against granting the full franchise to all citizens abroad. 'It would directly infuse the Irish electorate with emigrants who would skew many constituencies in directions which they would not normally go.' He proposes offering seats to emigrant representatives in the Irish senate, the upper legislative chamber. This body’s role is currently under review and is considered elitist and increasingly irrelevant. Allowing representatives of the diaspora seats might be one way to invigorate it.

European comparison

In fact, the outgoing government did propose establishing an independent electoral commission in 2009, which would have made recommendations for extending the franchise abroad for presidential elections only. With the economy taking centre stage, it’s hard to see it coming to fruition soon. A July 2010 European court of human rights (ECHR) ruling gives more hope that the government might be forced to act. In 2007, two Greek nationals living in Strasbourg petitioned that their right to vote was violated because they were living abroad. While they could have travelled back to Greece, the court found that the distance and expense involved complicated their right to vote, guaranteed under article 3, provision one of the European convention of human rights. Ireland, like all EU member states, is a signatory to the convention.

Meanwhile the United Kingdom allows its citizens abroad to vote in elections for a period of 15 years after they leave the country. But one world war two veteran is challenging the UK government’s ban on non-resident citizens voting after that period. Ninety-year-old Harry Shindler, who lives in Italy, also brought his case to the ECHR in late January. 'One major concern of the council of Europe is to preserve and strengthen democracy and civic rights of member states,' the court said in its request. 'Due regard should be given to the voting rights of citizens living abroad, an essential freedom in every democratic system.' Back in Ireland, Orlaith Finnegan takes consolation from indications that 'both [the governing] fianna fáil and the greens will be dealt a severe drubbing for their blistering incompetence on 25 February. With things the way they are, 'as a non-resident citizen, I'll be denied the sheer joy of exacting electoral revenge on the government.'

Image: (cc) photobunny/ Flickr