Ireland’s expat-emigrants: silver spoon diaspora

Published on

Thousands left Ireland when it was rollicking at the dizzy heights of an economic boom, and when ‘diaspora’ sounded like a chapter heading from Angela’s Ashes. Now that the country has all but gone bust, those who left in the good times have been transformed from ‘expat’ to ‘immigrant’ overnight. In 2010 they were joined by 65, 000 others fleeing the Republic’s economic collapse

Ireland’s 21st century emigrants are a rather different kettle of fish than the aunts and uncles who left to work as builders in London and Boston in the 1980s. Firstly, they’re drastically better educated: in response the huge wave of emigration in the eighties, the Irish government introduced free university education, hoping to seed global wealth that would eventually come back to Ireland. It worked: Irish-born success stories fuelled the domestic ‘Celtic Tiger’ economy on an international scale. Yet, while emigration came to a halt, free university continued – alongside a huge social pressure to avail of it, and today Irish universities are bursting at the seams. Secondly, this generation has wildly different expectations. ‘People who emigrated 20 to 25 years ago were looking for any kind of work,’ says Mark O’Brien - who runs a Gaelic football league in Toronto - to The Irish Times. ‘The newcomers tend to be very picky, turning their noses up at jobs they think are below them. They grew up with a silver spoon in their mouths.’

Getting a lick-in

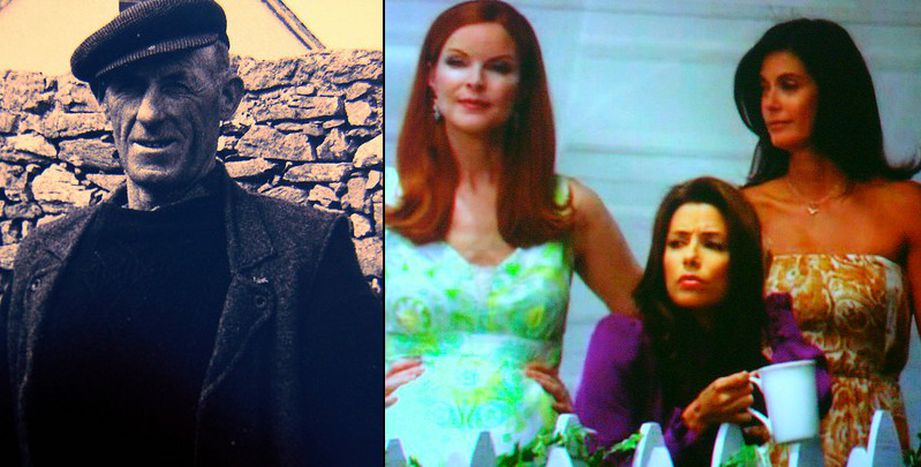

Even those Irish twentysomethings who didn’t get a lick of the ‘silver spoon’ might be forgiven for having a distorted view of their fiscal potential: after all, for fifteen years they watched everyone around them became exponentially wealthier with each coming year. The boom was brutally visual: houses quadrupled in size, villages were transformed. Ireland’s young generation is not only its ‘best and brightest’ but also the most ‘bourgeois’ the country has ever seen. The one-time army of builders hoping to earn the price of a pint has been replaced with a league of physiotherapists and dieticians, who fully expect a Desperate Housewives lifestyle. Accordingly, neither the carefree connotations of ‘expat’ nor the tractable intimations of ‘immigrant’ quite fit this social anomaly.

Even those Irish twentysomethings who didn’t get a lick of the ‘silver spoon’ might be forgiven for having a distorted view of their fiscal potential: after all, for fifteen years they watched everyone around them became exponentially wealthier with each coming year. The boom was brutally visual: houses quadrupled in size, villages were transformed. Ireland’s young generation is not only its ‘best and brightest’ but also the most ‘bourgeois’ the country has ever seen. The one-time army of builders hoping to earn the price of a pint has been replaced with a league of physiotherapists and dieticians, who fully expect a Desperate Housewives lifestyle. Accordingly, neither the carefree connotations of ‘expat’ nor the tractable intimations of ‘immigrant’ quite fit this social anomaly.

The new Irish diaspora are doing much the same things as their ‘expat’ predecessors during the booms years – most landing working visas to Australia, the US and Canada in the hopes of finding a job that will allow them to stay. The only discernable difference is that there are more of them now; their quest, likewise, has become rather more urgent. ‘Expat simply means professional immigrant,’ says John Heffernan, who left Ireland to study public international law at the University of Amsterdam. ‘I was always planning on going abroad for my masters, rather than leaving Ireland in response to the financial crisis.’ He is not alone: an army of high achievers that were once the envy of neighbouring nations is on the march out of the Republic. First-Honours graduate and one-time student president of Dublin’s prestigious Trinity College, Andrew Byrne worked with the green party and the ‘Ireland For Europe’ movement, but now lives and works in Germany. ‘While technically I'm an immigrant here, I know I will definitely return to Ireland in the future,’ says Byrne. ‘I think many young Irish people also feel the same and in the meantime cheap travel and Skype make touching base at home a lot easier.’

Certainly, the mechanics of emigration have changed a lot since the 1980s. Flying half way across the world for christmas is no longer the gargantuan feat it once seemed, and with Skype’s Star-Trek-style videophones, the days of call cards and phone boxes are long gone. In fact, for many, the renewed culture of emigration seems somewhat novel – fashionable even. Early in the new year, The Irish Times ran a story entitled ‘Emigration: The Next Generation,’ headed with a glitzy photo of a smiling blonde, proudly posing in New York’s Greenwich Village. The caption is: ‘If I Can Make it Here’. ‘Ideally, everyone should emigrate,’ asserts Steven Lydon, who originally left Ireland to study at Cambridge. ‘Learning how to establish yourself in an unfamiliar social environment is an admirable skill, and you begin to realise that home isn't the centre of the universe.’ Ideal or not, with a crumbling government, mounting taxes and a future leased out to IMF loan sharks, the youth of Ireland is fast running out of options. The long tradition of Irish emigration is back in full force, but this time the country is exporting a very different kind of worker. What is to become of the silver spoon diaspora in the unpredictable years to come however, is anyone’s guess.

Images: Illustration from Preface to the First Edition of An Illustrated History of Ireland from AD 400 to 1800, by Mary Frances Cusack, Illustrated by Henry Doyle scanned into 001.jpg extracted from Gutenberg project's z (1868)