Iran, Russia and the British council: getting geopolitical with Shakespeare

Published on

Translation by:

Lindsey EvansThe United Kingdom’s primary institution for representing its culture and language internationally has been embroiled in a diplomatic struggle for the past two years. Russia is pushing for the closure of its offices in Moscow and St Petersburg

Far from being simply a not-for-profit agency for English teaching overseas, the British council is an influential diplomatic instrument for the UK. Founded in 1934, its status is that of a non-commercial public service organisation. However, this noble institution, very well respected in the UK, is essentially run as a private company. Over 60% of its income is derived from selling language courses and from cultural sponsoring. But below the surface it has very strong, yet subtle, ties to the state.

Cultural frontline

The creation of the British council in the 1930s was masterminded by the foreign office and could potentially be seen as a response by cultural means to the rise of fascism. Under the terms of a 1940 royal charter, the organisation receives state subsidies to support its existence. The nature of its operations means that it collaborates closely with the foreign office to extend the UK’s presence abroad through language teaching, and to cultivate a positive image of the country.

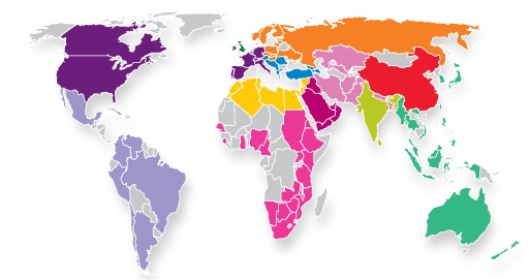

The British council’s strategy document Making a world of difference – cultural relations in 2010 measures the organisation’s level of cultural influence by looking at the attendance figures at its teaching centres and the traffic on its website. But, through this promotion of intercultural dialogue, it is British democratic principles and political values that are being disseminated. The British council offices overseas (of which there are 200 in 110 countries) can therefore be viewed as the cultural weaponry of the United Kingdom’s embassies.

The British council’s strategy document Making a world of difference – cultural relations in 2010 measures the organisation’s level of cultural influence by looking at the attendance figures at its teaching centres and the traffic on its website. But, through this promotion of intercultural dialogue, it is British democratic principles and political values that are being disseminated. The British council offices overseas (of which there are 200 in 110 countries) can therefore be viewed as the cultural weaponry of the United Kingdom’s embassies.

Staff forced to resign in Iran

The British council’s close links with the foreign office have made it the focus in diplomatic disputes over the past two years: the row between Britain and Russia over the November 2006 murder of ex-Russian spy Alexander Litvinenko in London led the Russian authorities to put pressure on the British council in Russia. The Kremlin responded to the UK’s extradition of four Russian diplomats in July 2007 by ordering the closure of 2 British council offices (in Yekaterinburg, central Russia, and St Petersburg), albeit on the pretext of a fiscal controversy. The crisis reached a peak in January 2008 with the arrest of Stephen Kinnock, director of the British council office in St Petersburg. Kinnock is the son of Lord Neil Kinnock, who became chairman of the British council in 2004.

At the beginning of 2009 it was Iran’s turn to target British council workers in an act of diplomatic confrontation. 16 Iranian employees were summoned to president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s office and ordered to leave their positions. At the same time, Iran refused to grant work permits to British employees of the organisation. As a result, the Tehran office was forced to suspend its activities.

Closures in Europe

Difficulties in Iran may be connected to a major shift in strategy that the heads of the British council decided upon in March 2007. They have pledged to focus energies on the muslim countries of the Middle East, with a view to cross the cultural barriers between our societies and helping to fight religious extremism. This change of tack has provoked strong reactions, since it has entailed several closures of British council offices in countries such as Lesotho, Ecuador and Peru and, particularly, within Europe – in Austria, the Baltic states, and Belarus.

Many questions are being asked – not least by British artists – about the real role this elite institution plays in cultural relations

Tying into the British council’s geographical and political reorientation was the decision to close its visual arts department, which proved a source of outrage for British artists. More than 100 leading figures in the art world, including Lucian Freud, Bridget Riley, Damien Hirst, David Hockney and Rachel Whiteread, signed a petition in January 2008 to condemn the large-scale revisions to the British council’s cultural policy that threatened to wind down visual arts, theatre, film and dance departments.

It seems that, while the UK enjoys the rewards (both linguistic and commercial) of selling English courses thousands of students across the globe, many questions are being asked – not least by British artists – about the real role this elite institution plays in cultural relations. Is the act of promoting a nation’s culture just a front behind which political ulterior motives are at play?

Translated from British Council : la géopolitique de Shakespeare