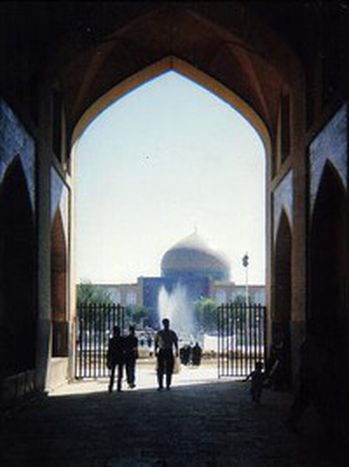

Iran, beyond nuclear containment

Published on

Translation by:

Morag Young

Morag Young

From weapons of mass destruction to weapons of mass attraction: new forms of independent media, supported by Europe, are needed to take a stand against the nuclear threat from Teheran.

The seats put aside for European negotiators were empty on August 31, the date initially set for restarting nuclear negotiations with Iran, signalling a mini turning point in relations between the European Union and Teheran. With the election of the reformist Khatami in 1997, many people, especially in Europe, had begun to hope for change and progress within the Islamic regime. But the election of the new President, the ultra-conservative Ahmadinejad, shows to what extent the institutions created by the 1979 'Islamic Revolution' were constructed in such a way as to be completely unresponsive to attempts at reform.

The real face of the regime

The imprisonment of Iranian journalist Akbar Ganji, increasingly frequent violence in the mainly Arab region of Ahwaz, raids against villages in Kurdish areas and the unilateral resumption of nuclear activity at the Isfahan facility demonstrate the regime's determination to pursue its own political path, ignoring both forces within its own country and pressure from the international community to change.

Democracy is the crux of the matter

Experience has shown that while side-stepping the question of Iranian democracy might permit Iranian diplomats and the EU to sit down at the same table, it does not guarantee stability in the region in the long term. The European Union is Iran's main trading partner and Teheran is an important source of European energy. But being a country's main trading partner entails additional responsibility and, in Iran's case, a greater duty to listen, including to those who are politically and economically excluded from the Islamic Republic's system of power.

30 million young people

The need to provide 'weapons of mass attraction', in other words new independent media modelled on Radio Londres, created by General De Gaulle to call the French to resist the Nazi occupation,

is more crucial than the increasingly imminent development of new weapons of mass destruction by Iran. We need to get beyond the sectional approach, which is the domain of technicians and nuclear inspectors, to develop an all-round strategy which gives priority to the promotion of democracy in Iran. A strategy based not only on negotiation and the search for stability in a region where commercial ties are worth, but also on the contradictions within the Teheran regime: a country where 50% of the population belongs to minority communities (including Azeris, Kurds, Arabs, Baluci and Turkmen) which are often discriminated against; a country where more than 30 million inhabitants were born after the 1979 revolution and want to enjoy the freedom of the Internet; a country where, still, being a woman means living with segregation.

What the repressed people of Iran want from Europe is more effort in promoting the path towards a new democratic, secular and federal political system, not least through information tools. The new Iranian President, Ahmadinejad, appears to want to be respected by everyone. It would be good news for Iranians, indeed for all of us, if, over the next few days, the EU is capable of respecting its own values.

Translated from Iran-Ue: oltre il containment nucleare