In The Bowels of Europe’s Conscience

Published on

Any one of 820m people can apply to the European Court of Human Rights without a lawyer and without a fee. It is extremely democratic but it is a victim of its own openness, receiving 60, 000 applications a year. Who are these people and how does this colossal judicial creature function? I met Kurds and cut-throats and a man reporting a murderous Japanese robot

“He will contribute to peace and democracy, so we’ve started a campaign for his release,” says Adem, a Kurd campaigning against the imprisonment of Abdullah Öcalan, leader of the Kurdistan Worker’s Party. In March 2014, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that Turkey had violated Öcalan’s rights by keeping him in “inhuman” conditions; ten years solitary confinement in an isolated island prison.

Adem and four other Kurds are gathered around posters of Öcalan on this leafy riverside avenue opposite the Strasbourg Court. They’re in high spirits after the ruling in Öcalan’s favour. Rather than looking back bitterly at a conflict with Turkey that claimed 40,000 lives, thanks to the ECHR, they are looking to the future with optimism. “We already have one million [signatures] and we’ve been here for two years,” Adem tells me proudly, “we’ll continue like people did the same for Mandela.”

Adem and four other Kurds are gathered around posters of Öcalan on this leafy riverside avenue opposite the Strasbourg Court. They’re in high spirits after the ruling in Öcalan’s favour. Rather than looking back bitterly at a conflict with Turkey that claimed 40,000 lives, thanks to the ECHR, they are looking to the future with optimism. “We already have one million [signatures] and we’ve been here for two years,” Adem tells me proudly, “we’ll continue like people did the same for Mandela.”

Inside Europe’s Conscience

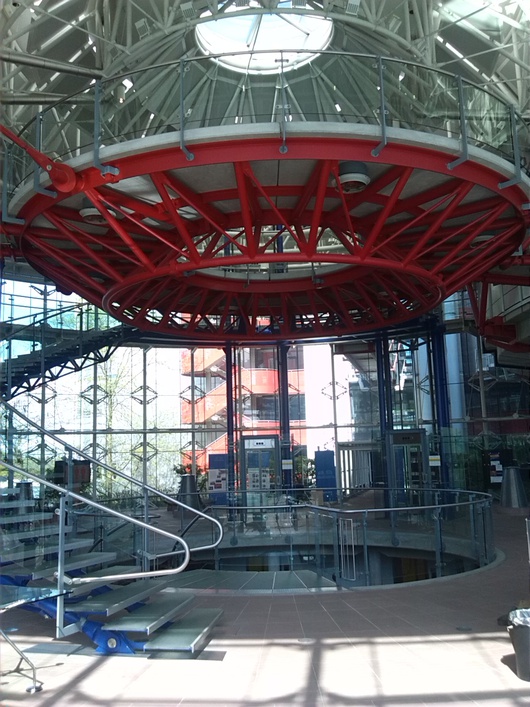

The ECHR consists of two colossal steel cylinders which shine brightly against the clear April sky. The building has an epic aura, like twin leviathans floating in the blue. They are connected by a web of glass and girders. Justice may be an ancient ideal, but “Europe’s conscience” feels like something from the future. The glass walls feel non-existent; you see through everything and nothing is hidden. Tracey Turner-Tretz, the Registry press officer, tells me the construction is symbolic of the transparency the court seeks to diffuse.

The ECHR consists of two colossal steel cylinders which shine brightly against the clear April sky. The building has an epic aura, like twin leviathans floating in the blue. They are connected by a web of glass and girders. Justice may be an ancient ideal, but “Europe’s conscience” feels like something from the future. The glass walls feel non-existent; you see through everything and nothing is hidden. Tracey Turner-Tretz, the Registry press officer, tells me the construction is symbolic of the transparency the court seeks to diffuse.

I meet Clare Ovey, Head of the UK Registry Division in a perfectly circular conference room. It is the width of one whole cylinder. A deep blue carpet with the EU stars embroidered in gold gives the impression that this court is not just in Europe, it is Europe, a corporeal embodiment of the values Europe was built on. The whole wall is a window, so Clare and I are bathed in a curiously balanced light. There are no shadows, only light.

“The convention system is there to protect minorities,” explains Ovey, “because you can assume in any sort of democracy that the majority can look after themselves, because they’ve got access to power- so it’s the minority interests that need rights.” She speaks quickly and with conviction, smiling behind her black rimmed spectacles.

Standing up to States

The Court has a history of protecting minority rights against powerful states. It made Russia pay over one million euros to the families of Chechens killed by the Russian army. The Court obliged Cyprus to properly protect victims of sex trafficking. It has forced the UK, Bulgaria, Switzerland and others to care better for the mentally ill. “Here you feel like your work is making a difference,” says Ovey.

But not everyone agrees. UK Justice Secretary Chris Grayling said the ECHR does not “make this country a better place.” When the Court ruled Britain’s blanket ban on prisoner voting violated the Convention, David Cameron said the thought of prisoners voting makes him “physically ill”. UK Home Secretary Theresa May has threatened to cut ties with the “interfering” ECHR.

What does the Court make of this backlash? Ovey spreads her hands in a gesture of gentle frustration. She partially blames the press, “That judgement has been reported as this court saying murderers and rapists should get the vote and that’s definitely not what it said.” But Ovey also attributes this recent vitriol to opportunistic but misdirected euroscepticism, “We’re coming up to the European elections and the way that the parties have divided themselves and presented themselves is turning on Europe,” she explains. “This court, even though we’re separate from the EU, we’re seen as part of that, and that’s why politicians and government ministers like to attack us.”

In any case, the extent of the Court’s intervention is exaggerated. A few judgements steal the headlines, but the Court rarely rules against member states. In 2013, out of 909 applications from the UK, only 13 were deemed a violation, yet the Tories claim the Court is seriously impinging on British sovereignity. Proposing an independent British human rights bill suggests human rights are not universal and can be applied selectively. Ovey says British foot-dragging is harmful for everyone; “The Ukrainian president basically said 'why should we bother enforcing our judgements when someone like the UK doesn’t?'”

How Does it Work?

Whereas national courts apply fixed judicial frameworks; “guilty or not guilty”, the ECHR’s job is to probe and improve these national frameworks; it’s more a question of “what is justice?” It's the only way an individual can challenge a state. Since anyone can apply with no fee and no lawyer, the Court receives 60, 000 applications a year and has 99, 000 pending. These figures sound huge, but what do they look like?

In the cavernous mail room, an army of filing cabinets stand to attention in neat rows. The ten administrators here speak 28 languages between them and they deal with 1,600 letters a day. I descend another level to the bowels of Europe’s conscience. These bowels are filled with valuable treasure; 60 years of justice. Justice as an ideal may be unquantifiable, but in practice it can be counted; as 5.2 km of archived documents to be precise. “That’s 36 times higher than the Strasbourg cathedral,” says Eliza, who works in the archives.

Plurality in Practice

Outside the Court, an encampment of protestors living in tents sprawls along the bank of the river Ill. Classical music drifts across the encampment. The protestors are not exactly what I was expecting. I meet Maimouna El Mazougui, a 73 year old Moroccan. She alleges that the French and Israeli governments colluded to plant a chip in her brain to control her remotely, making her vibrate and preventing her from doing God’s work. She is sitting in her tent on a camp chair clutching a little black radio. Crates of bottled water are stacked outside her tent. She’s here for the long haul- years already. “The planet is governed by a global band of criminals, murderers and neo-Nazi Jews,” she tells me, “I’m waiting here for justice.”

Outside the Court, an encampment of protestors living in tents sprawls along the bank of the river Ill. Classical music drifts across the encampment. The protestors are not exactly what I was expecting. I meet Maimouna El Mazougui, a 73 year old Moroccan. She alleges that the French and Israeli governments colluded to plant a chip in her brain to control her remotely, making her vibrate and preventing her from doing God’s work. She is sitting in her tent on a camp chair clutching a little black radio. Crates of bottled water are stacked outside her tent. She’s here for the long haul- years already. “The planet is governed by a global band of criminals, murderers and neo-Nazi Jews,” she tells me, “I’m waiting here for justice.”

Later I meet Jonathan Simpson, who shows me a long white scar on his neck, “The British secret services cut my throat,” he rages. He claims they have been waging a campaign of terror against him for decades. “I could write a whole book on dental abuse alone,” he tells me. “Look at that gum line. One set up after another. There was even a bogus dental practice. The building was obviously hired for the purpose, no patients, the minimum of décor, absolutely off the scale.” Another protestor, Moustafa from Bulgaria, tells me he has travelled 48 hours on the bus to come here and report a Japanese robot of Toyota make which killed his family with a laser. He unzips his leather jacket to reveal a torsoe wrapped in plastic; home-made armour.

Later I meet Jonathan Simpson, who shows me a long white scar on his neck, “The British secret services cut my throat,” he rages. He claims they have been waging a campaign of terror against him for decades. “I could write a whole book on dental abuse alone,” he tells me. “Look at that gum line. One set up after another. There was even a bogus dental practice. The building was obviously hired for the purpose, no patients, the minimum of décor, absolutely off the scale.” Another protestor, Moustafa from Bulgaria, tells me he has travelled 48 hours on the bus to come here and report a Japanese robot of Toyota make which killed his family with a laser. He unzips his leather jacket to reveal a torsoe wrapped in plastic; home-made armour.

Evidently some of these applications will not be accepted, but what matters is they are allowed to apply. The Court treats every application with dignity and without preconceptions. “I think it’s actually a very good sign,” says Iverna McGowan, Director of Programs at Amnesty International, “the Court’s values are based on a pluralistic society, democracy, values such as freedom of expression. Who are we to judge prima facie if someone has a valid case or not?"

This article is part of a special series devoted to Strasbourg. It's part of "EU-topia : Time To Vote", a project run by Cafébabel in partnership with the Hippocrène foundation, The European Commission, the Ministry of Foreign Affaires and the EVENS foundation. The whole series will soon be available on the homepage.