In Senegal, farmers versus Europe

Published on

Translation by:

catherine e. moir

catherine e. moir

Small-time Senegalese producers are speaking out against the Economic Partership Agreements (EPAs) negotiated on 8 and 9 December at Lisbon. For them, the battle against famine means being opposed to market liberalisation

It’s simple – in Senegal nobody knows the technical abbreviations used by European Commission civil servants. Except for one, EPA, which stands for Economic Partnership Agreements, letters that hit the country’s small producers where it hurts.

'We are trying to follow the negotiations under way between our leaders and the European Union. If these agreements are applied in their present state, we are heading straight for catastrophe,' explains Sidy Ba, the spokesperson for a group of groundnut farmers all situated in the Kaolack region, 200 kilometres south of Dakar, the groundnut basin of Senegal.

60% of this country’s population lives in a rural environment, and, according to the World Bank, one in three people live below the poverty line, with less than a dollar a day in their pocket. In other words, no matter how far away the EPAs are being negotiated, they are in the minds of all of Senegal’s small-scale producers.

These agreements will liberalise trading relations between the European Union and the countries of Africa, the Caribbean and the Pacific (ACP). The negotiations are drawing to a close. Moreover, the European Commission hopes to conclude the matter by the end of the EU-Africa summit, involving heads of state from European and African countries, on 8 or 9 December in Lisbon.

There is however no unanimity among the west African countries with regard to the EPAs. The negotiators from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) made demands during October that the negotiations continue and that the date set for signing the agreements be pushed back. Their main fear was that small-scale farmers will not benefit from the liberalisation of the market for agricultural products. According to them, this liberalisation could even pose a threat to local production. In the villages, they say, it would be even more difficult to feed all the hungry mouths.

Cotton and groundnuts, the key products

'The priority in the groundnut basin is not to open commercial borders  but first to increase the small farmers’ production capacity. We must fight famine which is eating away at them and give them the means to make a profit from their work,' Sidy Ba continues.

but first to increase the small farmers’ production capacity. We must fight famine which is eating away at them and give them the means to make a profit from their work,' Sidy Ba continues.

Awa Ndao is a mother of three girls and a disabled son. She is also grandmother to five grandsons and lives in the rural community of Ndiaffate, in the Kaolack region. She complains, 'I am at rock bottom, I am really doing everything I can to keep working and survive. But I have no strength left.' Living on just one or two meals a day, made up mainly of rice, she tells us 'we are hungy. Meat has become more and more scarce.'

Indeed, for the time being the Senegalese agricultural production organisation is not allowing farmers to fight famine. It is based on the presence of powerful middlemen who buy up the harvest directly from the small farmers to sell them on Senegal’s large markets and sometimes to export them.

Indeed, for the time being the Senegalese agricultural production organisation is not allowing farmers to fight famine. It is based on the presence of powerful middlemen who buy up the harvest directly from the small farmers to sell them on Senegal’s large markets and sometimes to export them.

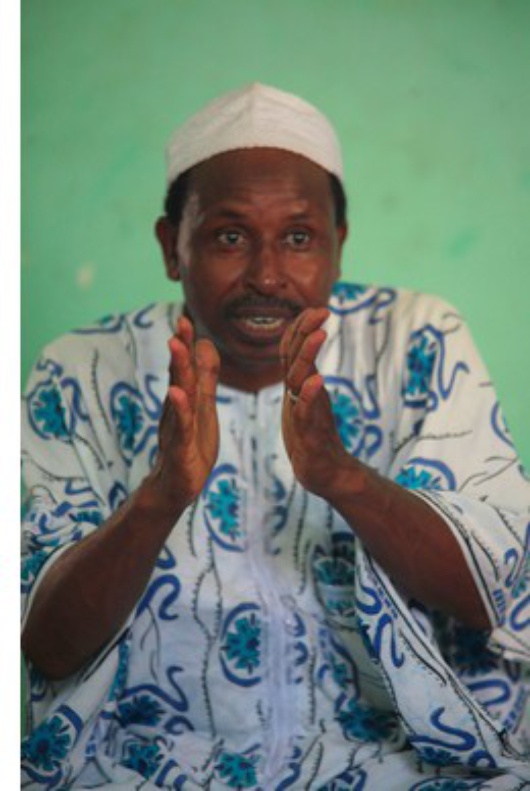

(Photo: José Lavezzi/ ActionAid)

'We don’t have enough good quality seeds and we have to get into debt to buy grain and fertiliser. When a dry period comes, we have to sell our livestock and our harvests at very low prices, which stops us from meeting our survival needs,' explains Adam Ibrahim Ndao, 50, groundnut producer in the rural community of Ndiaffate.

The food situation is worse still in Velingara region, a cotton basin in the south of the country, 700 kilometres from Dakar on the border with Gambia and Guinea Bissau. This year a famine was declared there following floods which destroyed the best part of the harvest.

'I am beginning to think that we will always be condemned to go hungry. My 80 year-old husband is too old to work our millet, cotton and groundnut fields and now it’s our 11 year-old son who farms our half hectare of land,' recounts Adama Sabally, a 60-year old mother of three, in the village of Pakour in Velingara region. 'We have at best one meal a day and this year the floods have destroyed all our harvests. We go more and more often for a whole day without food,' she continues.

'I am beginning to think that we will always be condemned to go hungry. My 80 year-old husband is too old to work our millet, cotton and groundnut fields and now it’s our 11 year-old son who farms our half hectare of land,' recounts Adama Sabally, a 60-year old mother of three, in the village of Pakour in Velingara region. 'We have at best one meal a day and this year the floods have destroyed all our harvests. We go more and more often for a whole day without food,' she continues.

Ensuring food sovereignty

'With the situation in Velingara, the priority for the small farmers is to get together in co-operatives to invest in fertilisers, tractors and seed reserves to be able to stand up to famine,' explains Abdoulaye Mballo, founder of the community radio station Radio Bantaare and correspondent for Senegalese Television Radio (RTS).

'With the situation in Velingara, the priority for the small farmers is to get together in co-operatives to invest in fertilisers, tractors and seed reserves to be able to stand up to famine,' explains Abdoulaye Mballo, founder of the community radio station Radio Bantaare and correspondent for Senegalese Television Radio (RTS).

'Senegal must urgently put into practice protection and develop ment policies for its national agricultural industries to combat hunger and strengthen national agricultural productivity,' explains Faty Kane, the young national coordinator of the Senegalese campaign to fight hunger, 'Kaa KonKo Kele'. 'This is the case with groundnut, the staple crop which also feeds livestock in Senegal. Developing this sector would allow us to stop importing products like soya oil from Europe or Brazil,' she adds.

Two days before the opening of the seventh EU-Africa summit in Lisbon, the message from small-scale Senegalese farmers is clear: they want west African countries to be able to copy Europe and set up a local common agricultural policy. They hope to become self-sufficient and protect the production of agricultural sectors essential to their economy, like groundnut or cotton.

Several organisations have been organising information campaigns about the EPAs for some months across the whole of west Africa. Will these efforts be sufficient to get their voices heard?

Photos of: Awa Ndao, Adam Ibrahim Ndao, Velingara region, Abdoulaye Mballo (José Lavezzi/ ActionAid)

Translated from Au Sénégal, les agriculteurs contre l’Europe