In search of lost time: The Jewish community in Wrocław

Published on

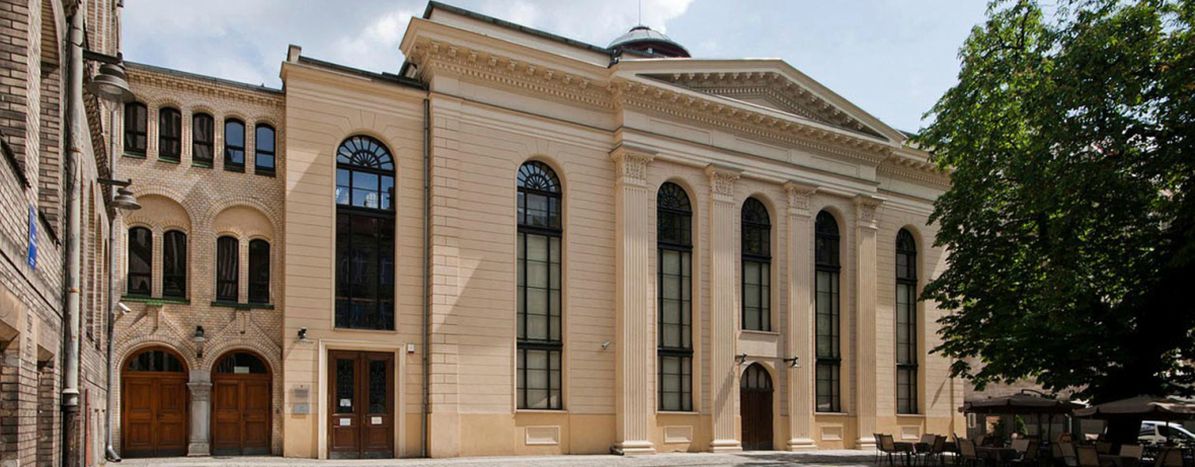

The White Stork synagogue in Wrocław was the only synagogue in the city to survive the Holocaust. Restored in 2010 after a decade-long renovation, it now serves as a cultural centre. But how much do people really remember of what happened here during the war?

There were two main synagogues in Wrocław before the Second World War, and many smaller ones. During the Kristallnacht in November 1938, when German citizens systematically ransacked Jewish-owned buildings and businesses, the White Stork synagogue suffered minor damage while the New Synagogue was completely destroyed. The White Stork was saved because of its proximity of other buildings in the city centre. Wrocław, bringing the name Breslau while being a German city back in the centuries, was the last stronghold of the Nazis during their retreat from the Allied forces. Its complex past is inevitably reflected in its identity in the present.

In mid-May, the White Stork synagogue was restored, and looked more like an empty gallery than a temple. Inside, there seemed to be an intense preparation for a concert. I had not been to a synagogue before, so I was peering with curiosity inside the building, when a woman vigorously pushed me out and said the building was closed for the moment. Then her voice softened, and she invited me to "the children’s concert" two hours later (the same children could be heard shyly singing obscure tunes from inside). "Oh, this will be a children’s concert… And I have no time..." I said to myself quickly.

Capturing fear

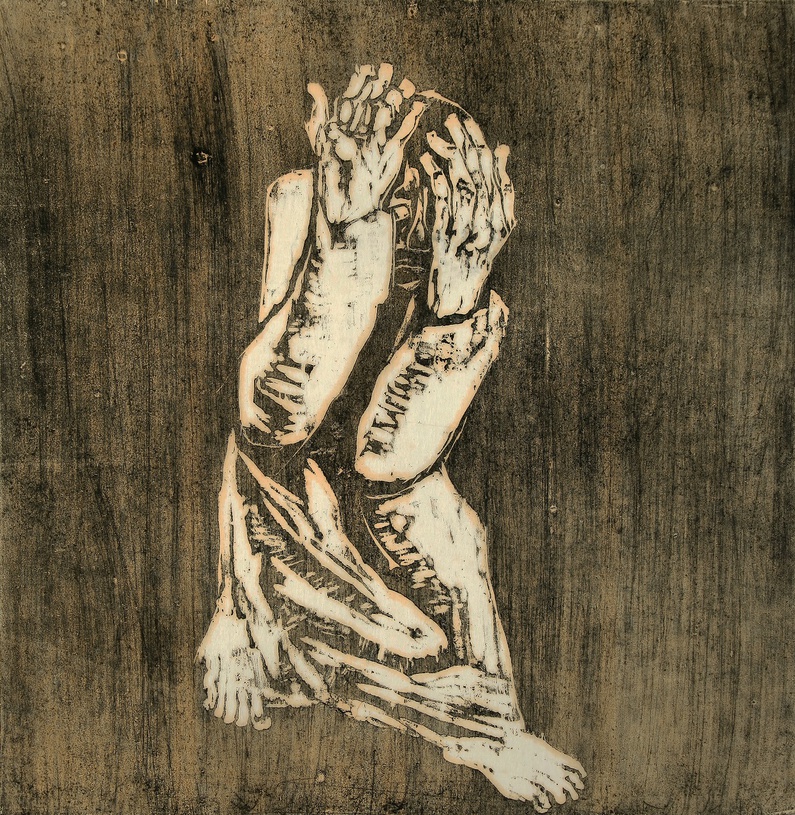

Later, my feet led me to the City Museum of Wrocław, to an exhibition of Jewish artists from the 1930s. It was a time of increasingly anti-Semitic Nazi propaganda, and Jewish artists could not pursue a career. For many, the only option was teaching. Then mass arrests began. Heinrich Tischler (1892-1938), painter and architect, was a central figure of the exhibition. A careful observer can gain a physical sense of what the word "fear" means from his paintings. The painter of another canvas, a still life with roses in bright colors, died in a concentration camp. The fate of many of those artists remained unclear.

Later, my feet led me to the City Museum of Wrocław, to an exhibition of Jewish artists from the 1930s. It was a time of increasingly anti-Semitic Nazi propaganda, and Jewish artists could not pursue a career. For many, the only option was teaching. Then mass arrests began. Heinrich Tischler (1892-1938), painter and architect, was a central figure of the exhibition. A careful observer can gain a physical sense of what the word "fear" means from his paintings. The painter of another canvas, a still life with roses in bright colors, died in a concentration camp. The fate of many of those artists remained unclear.

The first Polish exhibition of Jewish artists from Wrocław in the interwar period in 85 years had Heinrich Tischler’s work in its center. After the Kristallnacht, Tischler was deported to Buchenwald. Subsequently, he was released from the camp in 1938, but died a month later, due to the physical trauma he suffered there. Few Jewish artists persecuted in Europe by the Nazi regime after 1933 managed to survive and save their works.

While I was walking around the halls, staring at Tischler’s work and that of the other artists, my original decision not to go to the concert gave way to a peculiar determination to go. An elevated stage inside the synagogue was lit; the excited audience occupied only half the room. But the music made me stay on the bench until the very end, listening to the children’s crystal-clear voices. They expressed a very sincere faith in the goodness of people...

Wrocław's Jewish community

At present the scope of the officially registered Jewish community in Wrocław is approximately 350 people. Unofficially, it’s as high as 2000, but not everyone wants to register as part of it. Only a small number attends services regularly; most come only for high days and holidays. In general, the communities in Polish cities are quite small. However, Wrocław has incorporated a District of Mutual Respect here – a synagogue, protestant, catholic and orthodox church can be found in one neighborhood.

At present the scope of the officially registered Jewish community in Wrocław is approximately 350 people. Unofficially, it’s as high as 2000, but not everyone wants to register as part of it. Only a small number attends services regularly; most come only for high days and holidays. In general, the communities in Polish cities are quite small. However, Wrocław has incorporated a District of Mutual Respect here – a synagogue, protestant, catholic and orthodox church can be found in one neighborhood.

To learn more about the Jewish community in the city we talked with Katarzyna Andersz, project manager for the Bente Kahan Foundation, which focuses on different initiatives dealing with stereotypes and supporting the cultural life of the local community.

After the war, the White Stork Synagogue was once again used by the city’s Jewish population, which grew rapidly between 1945 and 1968. During the Cold War, it became state property – there were plans to turn the building into a library or a concert hall, but according to representatives of the Bente Kahan Foundation "no one did anything and it was just deteriorating, and by the late 80s it became a ruin." The Foundation started an initiative to restore the synagogue, and it reopened in 2010.

In November last year, an effigy of a Jewish person was burned in the market square of Wrocław during an anti-immigrantion rally led by a National-Radical Camp and All-Polish Youth. It is said to have evoked a lot of criticism from the mayor of Wrocław and local activists. A few months ago, a picture of Wrocław’s mayor Rafał Dutkiewicz wearing a kippah (he visits synagogues quite frequently for public events) was burned.

These are two bad examples, but still, says Katarzyna, "generally there’s no physical violence, and in fact there’s a lot of curiosity about Jewish culture." According to her, one could not say there are any bad attitudes among educated people. Katarzyna adds that many people who have discovered their Jewish roots are joining the communities now. But how much do people really remember of what happened here during the Holocaust?

"The population of Breslau does not live here anymore. The Jewish population was liquidated almost completely. Those who survived didn’t come back here, because the borders moved, and Breslau became Wrocław. Many of the people who have moved here after 1945 and the atrocities of the war (including a large group of Jews who were liberated from the camps in the Lower Silesia region or survived the war in the USSR), but they don’t know the history of the German town and very little about its legacy. It was sort of unpopular to refer to the German history of Wrocław, because for many years Poles wanted to make sure it is treated as a Polish city."

Tellingly, Katarzyna adds "caricatures of Jews counting money are still popular in Poland."