Immigration detention centres in France: move along, we're locking you up! (1/3)

Published on

Translation by:

Amélie HoussetWith a brand new draft bill on political asylum being presented to the French National Assembly, let's focus on one of the cornerstones of European immigration policy: immigration detention.

Over the 9th and 10th of December, French Home Secretary Bernard Cazeneuve, presented his draft asylum bill to the French National Assembly. This one is aiming at integrating European directives into the French legal system as well as shortening the decision-making process regarding asylum seekers.

However, Human Rights organisations and magistrates have condemned the assumptions and measures on which this bill is based. For example, the bill presumes that the asylum system is "full of fraudsters". Its opponents are worried about expediting the asylum procedure, which could affect judges' working conditions and even transform the asylum process in a "disallowing and deporting machine".

Therefore it is not so surprising that this draft bill does not even question the existence of immigration detention centres, set up by European states as a border control tool. And yet it is written in French and European laws that immigration detention should be used as "last resort". But is an immigration policy without immigration detention even an option ?

Immigration detention : What for?

Immigration detention facilities in France are officially named Centres de Rétention Admnistrative (C.R.A), which literally translates as Administrative Detention Centres. These facilities have been built in order to facilitate the deportation of foreign people who are not in possession of any type of residence permit in France.

Some of these people are asylum seekers who did not manage to go through the asylum procedures, which means they then find themselves without any residence permit on French territory. Others include who came to France with or without a visa, and then did not get or did not renew their residence permit. If the police happen to taken an interest in these individuals during an ethnic profiling identity check, they can then put in detention.

These immigration detention centres allow French authorities to "maintain" these people while requesting a "laissez-passer" to the country of origin, all that in order to deport them. Once this document has been delivered, the State can send these people back by plane.

The French authorities are allowed a certain time limit to get this laissez-passer. When this limit is exceeded (i.e. when the country of origin does not recognize the person as one of its citizens), the authorities have to free the detainee, even if he/she could not obtain a legal status.

The French authorities are allowed a certain time limit to get this laissez-passer. When this limit is exceeded (i.e. when the country of origin does not recognize the person as one of its citizens), the authorities have to free the detainee, even if he/she could not obtain a legal status.

It is important to note that even vulnerable individuals are imprisoned: pregnant women, sick people, old people, victims of torture or of human trafficking. Moreover, France as well as other European countries are still putting children in detention, accompanied or unaccompanied.

When were these detention centres created?

During the Glorious Thirties, France requested and allowed thousands of families and workers from Italy, Spain, Portugal, Tunisia, Marocco and Algeria to help rebuild the country and participate in its demographic growth. This lasted until 1974, when France tightened its borders. Workers and family-based immigration was suspended, with the exception of citizens from EC Member States. Strict controls were implemented, and foreigners were asked to possess a residence permit in order not to be deported.

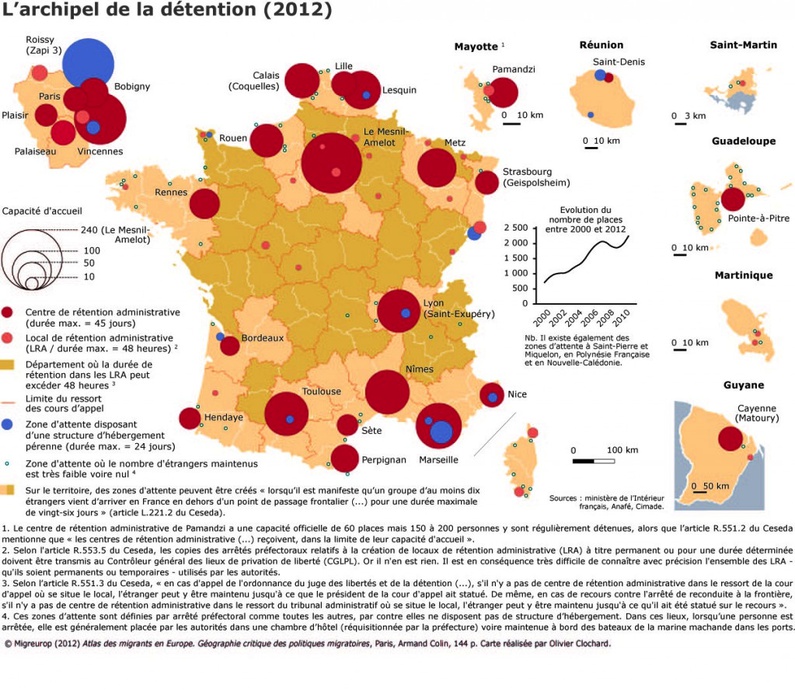

As soon as 1975, France began deporting people without any legal frame, using warehouses as illegal detention facilities. In 1981, a law was implemented in order to frame these procedures, with 13 immigration detention centres also being built in the main French cities. Since then, 12 others have been built. In addition to this, we count more than 150 other administrative detention facilities. The aim of these facilities is to temporarily welcome foreigners who could not be placed in detention centres due to "time or geographic" restrictions. They are mostly local police stations, and the detention in these places is limited to 48 hours.

The 1981 bill established the maximum time limit of detention to 7 days. Between 1993 and 1998, this time was extended to 10 and then 12 days, before being established at 32 days in 2003 by the Sarkozy bill. In 2011, the Besson bill extended it to 45 days.The Sarkozy bill also established - for the first time - a target of deportation orders: 15,000 in 2004, 20,000 in 2005 and 25,000 in 2006.

The 1981 bill established the maximum time limit of detention to 7 days. Between 1993 and 1998, this time was extended to 10 and then 12 days, before being established at 32 days in 2003 by the Sarkozy bill. In 2011, the Besson bill extended it to 45 days.The Sarkozy bill also established - for the first time - a target of deportation orders: 15,000 in 2004, 20,000 in 2005 and 25,000 in 2006.

How many people are locked up?

In 2013, 45,000 people were detained, and almost as many have been forcibly returned to their country of origin, according to a report from des cinq associations présentes dans les C.R.A [1]. If the number of people detained in camps has decreased since 2011 (when there were 51 000), the number of deportations has increased by 35% between 2011 and 2012. When a presidential candidate, François Hollande had committed to breaking the "policy conducted by the right-wing since 2007 ". But these figures show government investment from left and right in what many organisation call "the deportation machine."

How many people are locked up?

In 2013, 45,000 people were detained, and almost as many have been forcibly returned to their country of origin (Report of the five associations in the CRA [1], nes). If the number of people detained in camps has decreased since 2011 (when there were 51 000), the number of deportations has increased by 35% between 2011 and 2012. The candidate Holland had nevertheless committed to breaking the "policy conducted by the right figure since 2007 ". But these figures show government investment from left and right in that associations call "the deportation machine."

Hollande also committed to ending the detention of children. Despite these promises, and despite the condemnation of France by the European Court of Human Rights on this subject in 2012, 3,607 children were locked up in France in 2013, including 3,514 in Mayotte, in degrading conditions and without access effective to a judge.

Hollande also committed to ending the detention of children. Despite these promises, and despite the condemnation of France by the European Court of Human Rights on this subject in 2012, 3,607 children were locked up in France in 2013, including 3,514 in Mayotte, in degrading conditions and without access effective to a judge.

This article is part of a series of three articles on the detention centers for foreigners. Find tomorrow after our series.

[1] The five associations in administrative detention centres are Cimade, France Terre d'asile, Forum réfugiés-Cosi, l'Association service social familial migrants (Assfam) and l'Ordre de Malte France.

Translated from Centres de rétention pour étrangers : circulez, on enferme ! (1/3)