Illustrating 'indignados': revolution in comic books

Published on

Translation by:

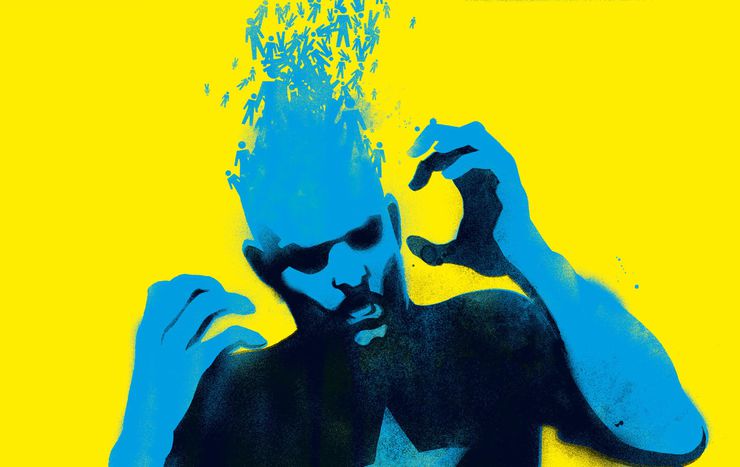

Tom GaleThe ‘indignant' movement is a publishing success in Spain. Two works in particular are illustrated, engaging and funny: Revolution complex and Enrique Flores' Cuaderno de Sol. The message is unequivocal: get involved or risk being sidelined

Revolution complex, published by Norma editorial, is the work of 22 different writers on a topical subject still bubbling with tension: the democratic uprising by the so-called ‘ni-ni’ generation which began on 15 May. The use of the collective reflects the difficult topic. It also plays into the collective nature of the citizen movement. The cartoonists are thus playing the self-deprecating card. ‘The first thing that was clear when we started Revolution complex was that we didn’t want to use it to ride on the coat tails of the indignant movement,’ explains ItalianClaudio Stassi, one of the authors. Irony is used as a weapon against doom and gloom, just like the clown face and the sunflowers that decorate Madrid’s central square, the Plaza de La Puerta del Sol while the Spanish riot police roll up their sleeves and reload their tear gas canisters.

Numerous authors have chosen to target the ruling classes: from Barcelona-based illustrator Danide, who paints the picture of an aristocrat flabbergast when faced with a young girl begging, to Sergi Alvarez, who depicts the finance ministers dictating to Spanish prime minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero and his rival Jose María Aznar the policies to follow in order to implement austerity measures. Except this time, these citizen-cartoonists have drawn their own roles. Aesthetics and political engagement have been put in the same boat but neither has been pushed overboard.

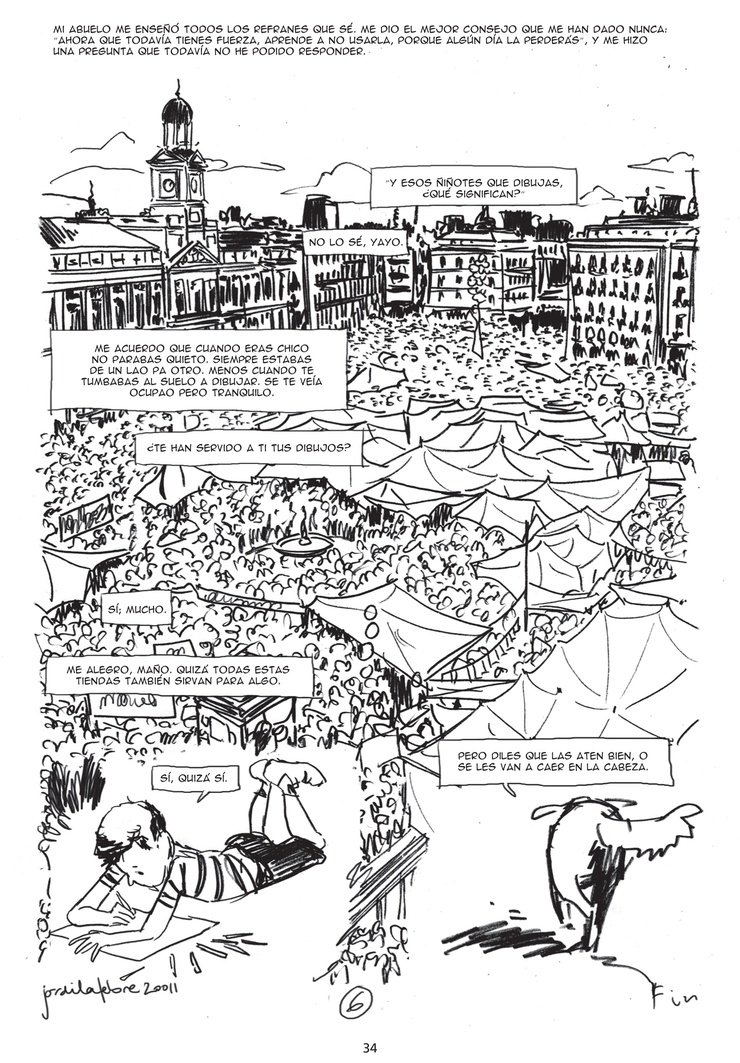

‘The campers, the 15-M movement and everything - it’s a complex and ample theme,’ explains Stassi, who is based in Barcelona. ‘In fact, we thought a lot not just about the story, but also about the title, the unitary idea of a book and its general concept.’ It’s all in the title. Catalan writer Jordi Lafebre offers a magnificent face to face between an indignant son and his father, who talks for a long time about the notion of participation and its multiple facets. Other writers focus on the romantic elements of the ‘indignant’ movement, those Spaniards who have decided to do everything they can to support the system such as it is.

After all, why shouldn’t they? Is history not a story of revolution and counter-revolution? These are humorous, diverse, stylised but also analytical stories. There are stories by journalist Jaumes Vidal and by Arcadi Olivers, president of Spanish NGO Justicia y Paz ('justice and peace'), stories by a priest, a journalist, a retired person, a restaurant owner, given life and drawn by Claudio Stassi. All give weight to journalist Jaume Vidal’s preamble: ‘The comic book proves that aesthetics and entertainment were not ignored because of our political engagement.’

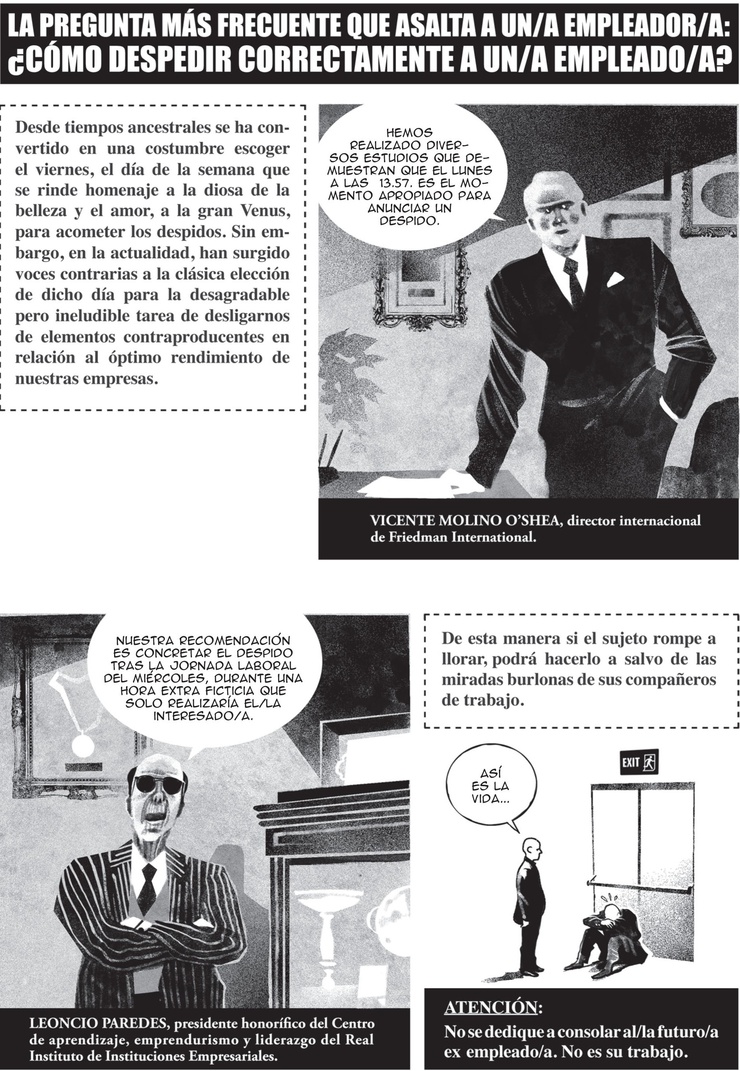

Future of journalism?

‘A new living and radical journalism has made its mark thanks to an approach which, far from fighting against the evolution of technology, has used it to spread and make itself heard,’ Vidal continues in the introduction of Revolution Complex. Undeniably nonconformist, the comics are being sold as effervescent tablets which are consumed through the visual, and are not to be read ‘if you are allergic to the welfare state or if the budget cuts do not affect your day-to-day life’. Humour and self-deprecation would probably do the world of journalism a great deal of good. Luckily, journalism has already come under attack from the blogosphere which has even reached the doors of reputable newspapers.

However, while journalism and social movements have a love-hate relationship, the man who joins the crowd at the Plaza de La Puerta del Sol with his sleeping bag, notepad and colouring pencils will instantly be welcomed into the family. Enrique Flores, a cartoonist from Extremadura in western Spain, did exactly that. His comic book Cuarderno de Sol ('Notebook of the Sun'), published by Blur editions, describes four weeks at the place where the 'indignant' movement started. From the street sweepers’ civic spirit to the pitching of tents via general meetings and late nights, Enrique Flores offers a subjective and humorous work of contemporary anthropology.

'A new, more human journalism is emerging'

A new journalism is emerging. This has nothing to do with forced objectivity, nor with cross checking sources. Instead it perhaps looks towards the ‘new journalism’ of 1960s America with its assumed subjectivity and intensive reportage. In other words: a more human journalism. Perhaps this is an idea for those who want to start their own revolution. In any case, as Claudio Stassi reminds us: ‘These days, the public goes straight to the information, it doesn’t wait around to be informed.’

Images: 'Revolucion Complex' © courtesy of Norma Editorial; videos/youtube

Translated from Les Indignés en BD : quand la révolution a bonne mine