Iberia: unite Spain and Portugal

Published on

Translation by:

Sophie Paterson

Sophie Paterson

28% of Portuguese and 45% of Spaniards want to unify Spain and Portugal

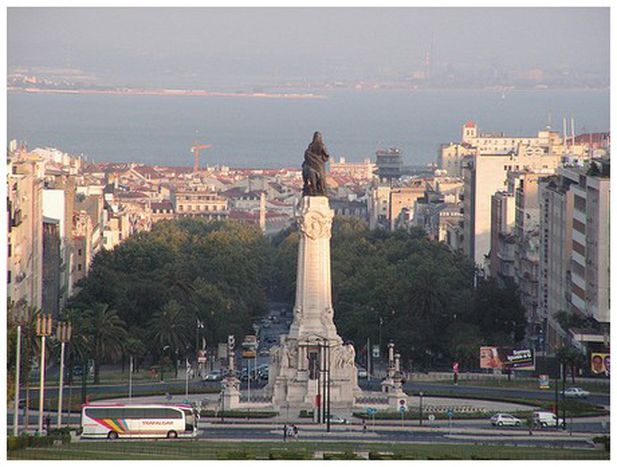

Lisbon. The EU capital with the oldest fixed borders. Sticking out in the unevenly-sized Plaza de Marqués de Pombal, is a copy of the Diário de Notícias, the newspaper with the widest circulation in Portugal. This morning, its comic strip transcribes a conversation between two neighbours in Beja, a Portuguese town bordering Spain. 'It was so nice to see Prince Felipe and Princess Letizia strolling through Beja!' – 'Don’t tell me that you’re one of those people who think that we should be Spanish!,' replies the other– 'No, no,' explains the first, 'I’m one of those people who think that the Prince and Princess should be Portuguese.'

Seldom a day goes by in which there is no news or joke in Portugal related to Spain. On top of nationalist complexes, the ideal of Iberianism is still being promoted in the country: the project, born in the 19th century in the minds of federalist republicans in both countries, is for the unification of Spain and Portugal, thereby creating a new state: Iberia.

Nationalist passions uncovered

Today, the most famous Portuguese Iberianist is Nobel Prize winner for Literature José Saramago – recently joined by another Nobel prize-winner, German Günter Grass. Saramago lives in Spain, and this summer declared his conviction to the media that 'Portugal will end up being integrated into Spain, forming a decentralised union.'

Today, the most famous Portuguese Iberianist is Nobel Prize winner for Literature José Saramago – recently joined by another Nobel prize-winner, German Günter Grass. Saramago lives in Spain, and this summer declared his conviction to the media that 'Portugal will end up being integrated into Spain, forming a decentralised union.'

Not all communists think the same. Fernando Bárbara, at the headquarters of the Portuguese Communist Party in the Lisbon district of Graça, swears to want 'to defend the national sovereignty of Portugal.' His fellow member João Narciso notes: 'We are against the cultural uniformisation in the Iberian peninsula, although it is true that both countries have common problems in the international sphere.'

The topic has unleashed a furore, and continues to produce certain crises, like that of the recent Socialist Minister for Industry, Mário Lino. His declaration that he was a 'staunch Iberianist', resulting in a heavy backlash from the conservative opposition who demanded an explanation and accused him of 'endangering the independence of Portugal.'

Much more than politics

'You can’t limit Iberianism to politics,' maintains Ramiro Fonte vehemently. He is director of the Instituto Cervantes in Lisbon, something akin to the Spanish cultural embassy in the Portuguese capital. 'It’s reductionist; a false debate created by slogans in the media,' adds the expert in Portuguese literature. 'Portugal unifying with Spain is political fiction.' A statement with which Portuguese Fernanda Menéndez, university professor in Spanish Linguistics, agrees, for whom 'unification is a utopia, because the Portuguese would create the same friction that already exists between Basques and Catalans with the rest of Spain. On the other hand, in terms of economy, integration is good: I think very highly of Iberianism as a strategy to defend our interests in Europe,' she emphasises.

Both stress the cultural aspect of Iberianism. 'Iberia is a pan-linguistic entity,' continues Menéndez, 'in which, excepting Euskara (the Basque language), we can all easily understand each other. We are all bilingual, although it would be good if the Spanish learned more Portuguese,' he laments in an unhesitant portuñol.

Both stress the cultural aspect of Iberianism. 'Iberia is a pan-linguistic entity,' continues Menéndez, 'in which, excepting Euskara (the Basque language), we can all easily understand each other. We are all bilingual, although it would be good if the Spanish learned more Portuguese,' he laments in an unhesitant portuñol.

'Portugal has always made more effort to get to know Spain than the other way round,' continues Ramiro Fonte. 'All Portuguese intellectuals mull over Iberianism, but these days Spain is becoming much more of an interest because Portugal is going through such a sense of crisis that it’s giving it a complex. It looks too much to Spain, which it has idealised,' he dares to warn. And adds: 'When both countries entered the EU, there was more confidence in Portugal than in Spain, a country that was too complicated, but now the Portuguese believe that Spain has fulfilled its duties better.' 'I,' concludes teacher Menéndez, 'dress like a Spaniard, eat like a Spaniard, I read Spanish, I’m married to a Spaniard and I lecture at the Universidade Nova in Lisbon, which is flanked by the El Corte Inglés shopping centre on one side and the NH Barcelona hotel on the other, both extremely Spanish things.'

If Iberia existed…

From a geographic point of view Portugal and Spain 'form one single entity facing the rest of Europe,' suggests Menéndez. With 1,214 kilometres of border without obstacles, these countries have always shared a common or parallel history. Joined together, they would form the biggest state in the EU, with 78 seats in the European Chamber. Since its entry to the EU in 1986, Portugal has quadrupled its export to Spain and tripled its import from said country.

From a geographic point of view Portugal and Spain 'form one single entity facing the rest of Europe,' suggests Menéndez. With 1,214 kilometres of border without obstacles, these countries have always shared a common or parallel history. Joined together, they would form the biggest state in the EU, with 78 seats in the European Chamber. Since its entry to the EU in 1986, Portugal has quadrupled its export to Spain and tripled its import from said country.

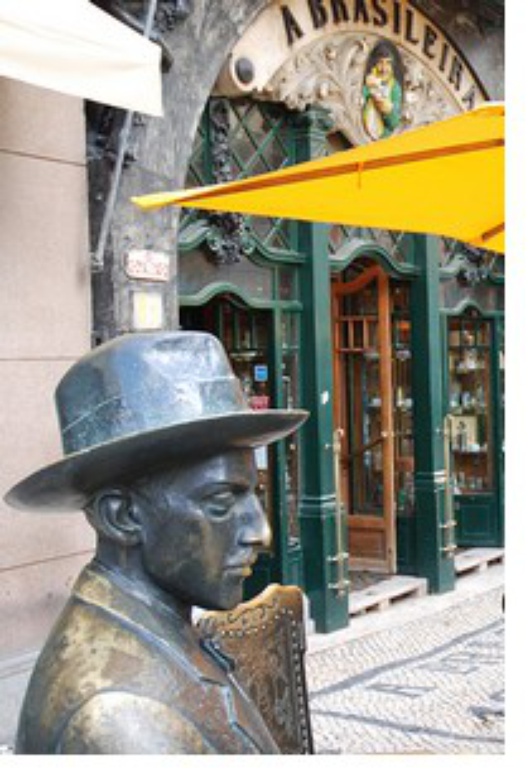

In the elegant street 'Garret y Largo de Chiado', right in the heart of the city, new Spanish bestsellers leap into view from the display windows of bookshops Bertrand, Portugal and Aillaud & Lellos. Spanish authors are everywhere: Julia Navarro, Enrique Vila-Matas, Javier Marías … all below the tireless gaze of the great Lisbon poet Fernando Pessoa, seated unperturbedly on the terrace of the mythic Café A Brasileira.

In-text photos: Nobel prize winner José Saramago (La Dulcinea/ Flickr), Illustration published in the spanish daily El País about 'Iberiasm' (Zone41/ Flickr), statue of Fernando Pessoa in the terrace of the café A Brasileira in Rua Garret, Lisbon (Hect/ Flickr)

Translated from Iberia empieza en Lisboa