"I am also...": Douglas Gordon Exhibition at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art

Published on

In January 2013, a major survey exhibition of Douglas Gordon, a British-born, Berlin-based and internationally celebrated contemporary artist, opened at the Tel-Aviv Museum of Art, Israel.

On January 25, 2013, a major survey exhibition of Douglas Gordon, a British-born, Berlin-based and internationally celebrated contemporary artist, opened at the Tel-Aviv Museum of Art, Israel. Beside offering a retrospectively oriented panoramic view of his works from last two decades, some of which have become iconic in their right in the meanwhile, such as 24 Hour Psycho (1993), 30 Seconds Test (1996), and Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait (2006), this exhibition puts into a poignant relief the contrasts that the recently inaugurated contemporary art wing of the museum makes palpable. At its most straightforward, this exhibition draws attention both to the museumification of contemporary art and to the shifting relations between various centers and peripheries that international exhibitions plumb.

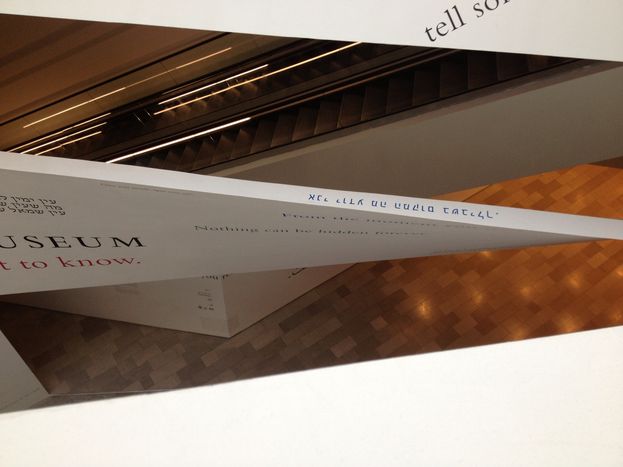

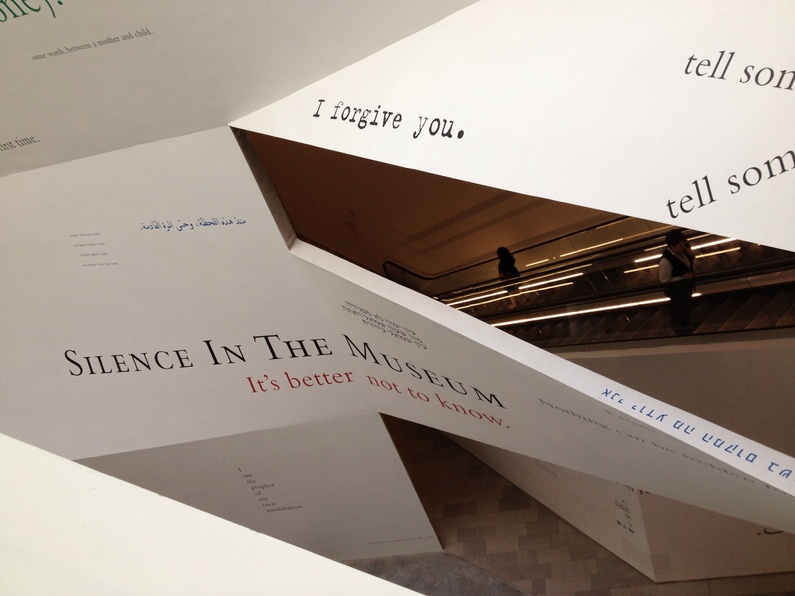

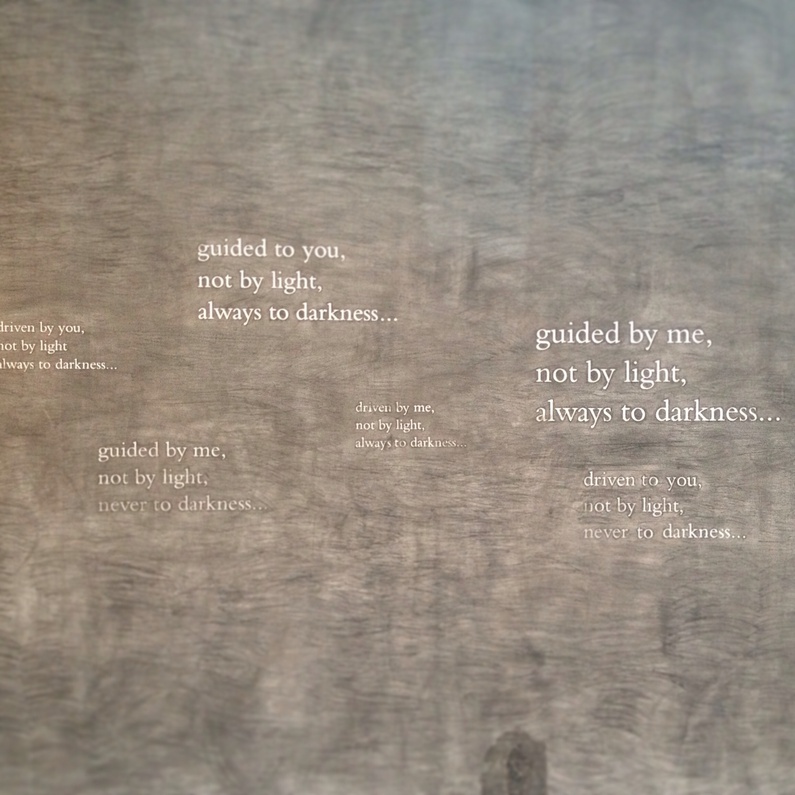

As the Tel Aviv Museum of Art unveiled its new architectural wing that doubled the total exhibition space of the museum, Israeli contemporary art gained a space of its own for a permanent exhibition. Thus the upper floors of this contemporary wing exhibit different stages of the development of Israeli art from the beginnings in the 1940s, its different periods stretching into the 1980s, and the present moment roughly starting in the 1990s. Additional spaces along the angular staircases and passageways that highlight the particularities of this architectural addition to extant museum exhibition areas host temporary exhibitions by local and international artists, such as John Stezaker, whose photo-collages are currently exhibited in one of these complexly carved spaces. However, while many of Douglas Gordon's video works could also be installed in generic galleries around the world, it is the in-between set of wall planes and their multifaceted inflections called the Light Fall by Preston Scott Cohen, the building's architect, where close to a 100 word art works by Gordon become uniquely installed in this museum. Furthermore, in one of the side-spaces of the building a panel composed of multiple TV- and video-screens offers a palimpsest-like retrospective of Gordon's various video artworks also captures the uniqueness of the experience this exhibition offers since the open and unconventional design on the space blends the panoramic views of the Light Fall with the richness of the representation that Gordon's receive at this exhibition.

As the Tel Aviv Museum of Art unveiled its new architectural wing that doubled the total exhibition space of the museum, Israeli contemporary art gained a space of its own for a permanent exhibition. Thus the upper floors of this contemporary wing exhibit different stages of the development of Israeli art from the beginnings in the 1940s, its different periods stretching into the 1980s, and the present moment roughly starting in the 1990s. Additional spaces along the angular staircases and passageways that highlight the particularities of this architectural addition to extant museum exhibition areas host temporary exhibitions by local and international artists, such as John Stezaker, whose photo-collages are currently exhibited in one of these complexly carved spaces. However, while many of Douglas Gordon's video works could also be installed in generic galleries around the world, it is the in-between set of wall planes and their multifaceted inflections called the Light Fall by Preston Scott Cohen, the building's architect, where close to a 100 word art works by Gordon become uniquely installed in this museum. Furthermore, in one of the side-spaces of the building a panel composed of multiple TV- and video-screens offers a palimpsest-like retrospective of Gordon's various video artworks also captures the uniqueness of the experience this exhibition offers since the open and unconventional design on the space blends the panoramic views of the Light Fall with the richness of the representation that Gordon's receive at this exhibition.

Indeed, Douglas Gordon and Ami Barak, a guest, Paris-based curator for this exhibition, self-consciously play on the contrast between the contemporary orientation of the new wing and the modern and classical works of art that the preexisting museum building exhibits. The works by Gordon one encounters at the basement level of the old wing of the Tel Aviv Museum include a high-resolution video recording of a classical music concert. The mirror reflection by the inner wall of the darkened room returns the gaze toward the double video projections that the majority of his large-scale works for this exhibitions constitutes. Thus, Gordon reflects the artistic and theoretical discourse on artistic media that have long been definitive of how art was traditionally perceived. In other words, being quintessentially contemporary, post-modern and reproducible medium, video projections and video screens of video art contrast with painting canvases that characterize most of classical and modern Western art. Due to their sheer scale, Gordon's video works also have something of sculptures due to their monumentality enhanced by high-fidelity sound-track too. This concern with artistic media is also evident in Gordon's word artworks in the Light Fall area that combine site-specificity with quintessential reproducibility of the printed, or, in this case, painted, word.

Indeed, Douglas Gordon and Ami Barak, a guest, Paris-based curator for this exhibition, self-consciously play on the contrast between the contemporary orientation of the new wing and the modern and classical works of art that the preexisting museum building exhibits. The works by Gordon one encounters at the basement level of the old wing of the Tel Aviv Museum include a high-resolution video recording of a classical music concert. The mirror reflection by the inner wall of the darkened room returns the gaze toward the double video projections that the majority of his large-scale works for this exhibitions constitutes. Thus, Gordon reflects the artistic and theoretical discourse on artistic media that have long been definitive of how art was traditionally perceived. In other words, being quintessentially contemporary, post-modern and reproducible medium, video projections and video screens of video art contrast with painting canvases that characterize most of classical and modern Western art. Due to their sheer scale, Gordon's video works also have something of sculptures due to their monumentality enhanced by high-fidelity sound-track too. This concern with artistic media is also evident in Gordon's word artworks in the Light Fall area that combine site-specificity with quintessential reproducibility of the printed, or, in this case, painted, word.

As a retrospective this exhibition's main underlying theme is memory and remembrance. In a sense, this exhibition presages the future archive of Gordon's artworks that through its very accumulation via museum and biennial exhibitions forces a historicizing look at his oeuvre. In the case of this exhibition, this consideration coincides with the process of the museumification of contemporary art that the new museum wing brings to the fore. The impression one receives from walking through the multiple museum spaces where Gordon's works are installed is that art history seems to have reached an inflection point of sorts when contemporary art becomes as historical as modern art is, which forces a search for a new definition of the work of the artists of the present day. I would venture to say that it is global art that tentatively supersedes or more correctly surveys the development of contemporary art from the vantage point of the decades that have passed since its formative moments in the 1960s. Since that time rock-and-roll music, New Wave Cinema and French theory have ushered in the archives of popular culture, stylistic innovations and theoretical ruptures that have largely defined the contemporary cultural moment until the 1990s, when their postcolonial, postmodern and poststructural reassessments have increasingly taken hold.

As a retrospective this exhibition's main underlying theme is memory and remembrance. In a sense, this exhibition presages the future archive of Gordon's artworks that through its very accumulation via museum and biennial exhibitions forces a historicizing look at his oeuvre. In the case of this exhibition, this consideration coincides with the process of the museumification of contemporary art that the new museum wing brings to the fore. The impression one receives from walking through the multiple museum spaces where Gordon's works are installed is that art history seems to have reached an inflection point of sorts when contemporary art becomes as historical as modern art is, which forces a search for a new definition of the work of the artists of the present day. I would venture to say that it is global art that tentatively supersedes or more correctly surveys the development of contemporary art from the vantage point of the decades that have passed since its formative moments in the 1960s. Since that time rock-and-roll music, New Wave Cinema and French theory have ushered in the archives of popular culture, stylistic innovations and theoretical ruptures that have largely defined the contemporary cultural moment until the 1990s, when their postcolonial, postmodern and poststructural reassessments have increasingly taken hold.

Likewise, Gordon's magisterial video work Zidane (2006) is concerned with memory, media, and representation, as a detailed documentation of a soccer match at the visual focal point of which stands Zinedine Zidane, an Algerian-born French footballer. This subtly constructed work closely follows through exaggerated close-ups Zidane's movements at the soccer field as he is playing one of the routinely screened matches. Aside of showing his mastery of the visual medium of technically challenging video recording, Douglas Gordon enters into a wider field of discourse over both contemporary and global art, as he makes his viewers pay attention to their activity of perception, recollection, and reflection that is engaged by this work in a self-referential manner. Double takes from different video angles at the sports field, documentary footage from war zones, and citations from the 24-hour news cycle that make part of the global media environment in most parts of the world make one reflect on how the relationships between the global and the local dimensions of everyday life are constructed.

Likewise, Gordon's magisterial video work Zidane (2006) is concerned with memory, media, and representation, as a detailed documentation of a soccer match at the visual focal point of which stands Zinedine Zidane, an Algerian-born French footballer. This subtly constructed work closely follows through exaggerated close-ups Zidane's movements at the soccer field as he is playing one of the routinely screened matches. Aside of showing his mastery of the visual medium of technically challenging video recording, Douglas Gordon enters into a wider field of discourse over both contemporary and global art, as he makes his viewers pay attention to their activity of perception, recollection, and reflection that is engaged by this work in a self-referential manner. Double takes from different video angles at the sports field, documentary footage from war zones, and citations from the 24-hour news cycle that make part of the global media environment in most parts of the world make one reflect on how the relationships between the global and the local dimensions of everyday life are constructed.

Situated at multiple global peripheries, Israel is a tantalizing background for this exhibition as a vantage point from which to reflect on the relationships between modernity and postmodernity, media and representation, and globalization and localization. Though already widely exhibited internationally, Douglas Gordon receives a very prominent spotlight at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art that tighter exhibition schedules and space constraints at, for example, the Museum of Modern Art New York might have made less possible. In other words, in Israel this exhibition appears to be a much more international event than it would be in more globally central locations. This tendency seems also to indicate that in this global moment, global peripheries gradually gain a greater purchase on the formation of global art, its history and discourse than ever before, precisely because of the lingering imbalances in cultural weight that different institutions, cities, and countries have.

Situated at multiple global peripheries, Israel is a tantalizing background for this exhibition as a vantage point from which to reflect on the relationships between modernity and postmodernity, media and representation, and globalization and localization. Though already widely exhibited internationally, Douglas Gordon receives a very prominent spotlight at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art that tighter exhibition schedules and space constraints at, for example, the Museum of Modern Art New York might have made less possible. In other words, in Israel this exhibition appears to be a much more international event than it would be in more globally central locations. This tendency seems also to indicate that in this global moment, global peripheries gradually gain a greater purchase on the formation of global art, its history and discourse than ever before, precisely because of the lingering imbalances in cultural weight that different institutions, cities, and countries have.

At the same time, the sheer possibilities that the medium of video projection, as illustrated by the complex and charged work Henry Rebel (2011), seem to be part of relatively recent period cultural, economic and technological development that enabled both globalization and the more spectacular forms of contemporary art, such as video installations. Tracing the nomadic global flows in his residences in multiple cities around the world, Douglas Gordon adds, thus, Tel Aviv to a global geography of irreducibly local places that in the process of this encounter gains in association not only with contemporary, but also global art.

At the same time, the sheer possibilities that the medium of video projection, as illustrated by the complex and charged work Henry Rebel (2011), seem to be part of relatively recent period cultural, economic and technological development that enabled both globalization and the more spectacular forms of contemporary art, such as video installations. Tracing the nomadic global flows in his residences in multiple cities around the world, Douglas Gordon adds, thus, Tel Aviv to a global geography of irreducibly local places that in the process of this encounter gains in association not only with contemporary, but also global art.