'I am a skinhead from Moscow'

Published on

Translation by:

claire hooper

claire hooper

Russian magistrates, politicians and media are concealing more and more racist attacks on foreigners

On 13 June, the public prosecutor of Krasnodar in southern Russia convicted Sergei Ivanizky, 19, of attacking Mahdud Ali Babikir, a Sudanese student of Krasnodar State University, with a knife. The defendant was sentenced to eleven years in prison for attempted murder and theft. The Ali Babikir case isn’t an isolated incident. In Russia, over the last year and a half not a week has gone by without the violence of extreme-right sympathisers.

According to Sowa, the Muscovite centre of information and analysis, the number of racially-motivated hold-ups has increased by 30% between autumn 2006 and spring 2007. During the first four months of 2007, 172 people fell victim to extreme-right criminals and 23 of them died.

The case of the student Ali Babikir is typical for another reason – just as for many similar trials in Russia, the 2004 article 282 of the penal code, which concerns the 'concealment of extremist incidents', was not used. This article makes spreading racist ideas as well as acts of violence motivated by racism or nationalism punishable by law. ‘It is clear that putting a stop to hate crimes isn’t one of the judicial system’s priorities,’ assessed the SOWA institute.

‘If you want I’ll kill you too’

The Babikir case also highlights the way Russian magistrates turn a blind eye to increasing racism. Ali Babikir and Ivanizky met in the street the evening of 4 July 2006, exchanged words and then came to blows. The attacker wounded the Sudanese man several times with a knife and stole his mobile telephone. Ali Babikir was discovered at 3am and was taken to hospital. He remained in a coma for several weeks. The day following his attack, the attacker was arrested, having been located thanks to the calls he received on the stolen mobile. Friends of Ali Babikir had the same reply each time they tried to contact him on his mobile: I am a skinhead from Moscow. If you want, I can kill you too.

Several of Ali Babikir’s compatriots were interrogated by the police over the course of the investigation. During the interrogations, the police officers showed them the student card of the attacker, Ivanizky, on the back of which the letters ‘SS’ were emblazoned in the shape of lightening.

The public prosecutor charged Ivanizky with attempted murder and theft, but not of having committed these acts with a racist motive. Such a process is part of a systematic judicial practice according to the SOWA institute: ‘There is no obligation to record suspicions of racism, which means prosecution for hate crime can be prevented in the majority of cases,’ plead experts. Even if the law, politicians and the administration seek to conceal it, anyone who looks ‘non-Slav’ can be victim of a racist crime in Russia.

Pushing this theory a little further, ‘EtnIKA’, an NGO based in Krasnodar, carried out an inquiry in collaboration with the Youth Human Rights Movement network on the groups of the population the victim Mahdud Ali Babikir belonged to – foreign students in Russia and particularly in Krasnodar are considered especially vulnerable.

Conflict at the round table

Foreign students principally fear for their safety off-campus, many having experienced conflict themselves. Such are the results of an investigation revealed by ‘EtnIKA’ in January 2007 at a round table with the inhabitants of Krasnodar. Alexandr Vaschenko, the representative of the university’s international relations department, was among those present.

According to Anastasia Denisova, president of EtnIKA, Vaschenko viewed the organisation’s work as an attack on his work. Still, according to Denisova, he telephoned a foreign student on his mobile so that he would state in front of the cameras that everything was fine in Krasnodar and that he did not feel in the least discriminated. For numerous reports broadcast on television, the Ali Babikir case was classified as a case of hooliganism and theft, but not extreme-right.

Shortly after this conference, Denisova received a letter from the Russian authorities explaining that the inspections they were carrying out go against Russian law concerning NGOs. Since then she has been obliged to give justificatory documents, and members of the organisation have been summoned on several occasions to be interviewed by the authorities. ‘Our work has been paralysed for the last few months,’ recounts Lyubov Penyugalova, a member of EtnIKA. Until now, instead of acting, EtnIKA associates, who describe themselves as a ‘group of youths in favour of tolerance’, have only provided explanations, invoices and files.

Meanwhile, Krasnodar municipality has had a study carried out concerning the position of foreign students. According to Alexandr Vaschenko, the majority of them feel fine. Nobody is scared of moving around freely in the town, and if conflict arises, it is certainly not down to their nationality.

No sign of open debate

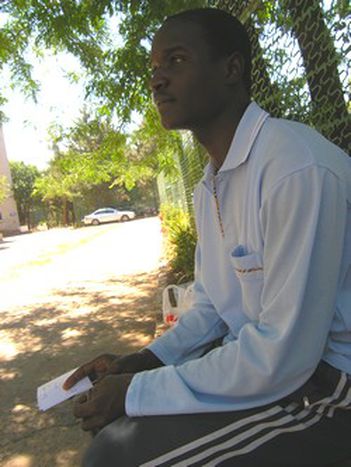

A student from Chad, who prefers not to disclose his name, is idling in front the hall of residence on Krasnodar university campus. ‘Yes, naturally the blacks are discriminated against here,' he says of the situation. 'I’m even scared of walking in the street.’ When we bring up the case of Babikir, he maintains he ‘does not want to talk about it.’ It the holiday period, and a lot of students have left town to go to the Black Sea.

Among the Russian students who are still there, only a few of them have heard about the attack on their peer. One could forget all about the matter if, and only if, the ‘non-Slavs’ no longer had to suffer from their appearance in Russia. But Russia is still a long way off opening the debate.

Translated from Totgeschwiegen: Ausländerfeindlichkeit in Russland