Huzun, bourgeois, opposites: what is Orhan Pamuk’s Turkey?

Published on

Translation by:

Cafebabel ENG (NS)Negotiations over Turkey’s accession to the European union began in 2006 but Europeans remain on their guard; the fear of the unknown is well known. The nobel literature prizewinner is one of Turkey’s main figureheads though he was accused of insulting Turkish identity. View from Poland

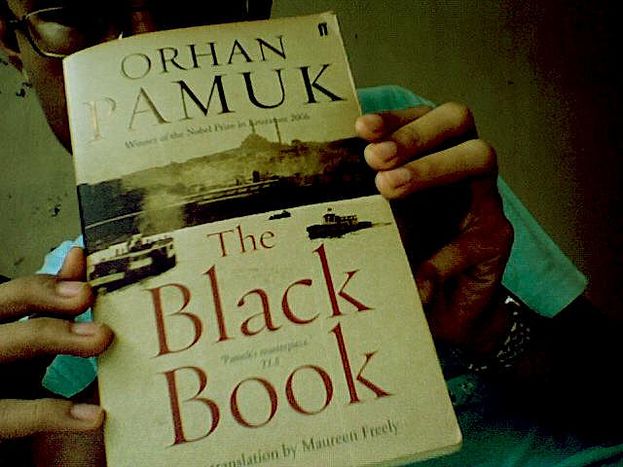

In 2006, the same year in which he received the nobel literature prize, Orhan Pamuk was listed as one of the one hundred most influential personalities in the world by Time magazine. He has sold well over seven million books, which have been translated in more than fifty languages. How to explain that the most well-known Turkish author, who has spent his life in Istanbul writing about his country and its inhabitants, is judged an enemy of the nation? In 2005, Pamuk risked a four-year prison sentence for having told Swiss newspaper Tages Anzeiger that ‘thirty-thousand Kurds and a million Armenians were killed in these lands, and nobody but me dares to talk about it.’ The author of My Name Is Red (1998) doesn’t universally describe Turkey as a beautitul, oriental and mysterious country – his Turkey which is beautiful in its authenticity but with its complexes, a torn country looking for its own identity. Orhan Pamuk also comes from a bourgeois background, having grown up in the chic, westernised neighbourhood of Nisantasi, coming from an atheist family where the only religion was literature.

Huzun

‘Happy is he who says, I am a Turk,’ the secular nation's founder Mustafa Kemal Atatürk once said. Pamuk’s books paint a different picture. The vision of the grandeurs past and lost weighs on the Turks. That’s why national pride is incessantly confused with complexes. All of this is at the origin of the phenomenon of hüzün that the writer describes in his book Istanbul: Memories and the City (2005). Huzun is melancholy, it is depression. It’s not something an individual experiences, but it is a general feeling, the state and soul of a culture in which millions participate. Learning about how Turkish people experience huzun tells us a lot about their attitude towards life and the reality surrounding them. Pamuk says that they suffer despite the choices they make and that their sufferance is full of vanity. In Istanbul: Memories and the City Pamuk writes: ‘So it was for the heroes of the Turkish films of my childhood and youth, and also for many of my real-life heroes during the same period: They all gave the impression that because of this hüzün they'd been carrying around in their hearts since birth they could not appear desirous in the face of money, success, or the women they loved.’ For the Istanbulites, hüzün is a sort of poetic license which justifies their detachment.

‘Happy is he who says, I am a Turk,’ the secular nation's founder Mustafa Kemal Atatürk once said. Pamuk’s books paint a different picture. The vision of the grandeurs past and lost weighs on the Turks. That’s why national pride is incessantly confused with complexes. All of this is at the origin of the phenomenon of hüzün that the writer describes in his book Istanbul: Memories and the City (2005). Huzun is melancholy, it is depression. It’s not something an individual experiences, but it is a general feeling, the state and soul of a culture in which millions participate. Learning about how Turkish people experience huzun tells us a lot about their attitude towards life and the reality surrounding them. Pamuk says that they suffer despite the choices they make and that their sufferance is full of vanity. In Istanbul: Memories and the City Pamuk writes: ‘So it was for the heroes of the Turkish films of my childhood and youth, and also for many of my real-life heroes during the same period: They all gave the impression that because of this hüzün they'd been carrying around in their hearts since birth they could not appear desirous in the face of money, success, or the women they loved.’ For the Istanbulites, hüzün is a sort of poetic license which justifies their detachment.

The writer gives a sad image of his compatriots. They escape life because they are afraid of failure, live in security in the chains of anxiety, nostalgia and unrealised dreams. The permanent battle between east and west, between tradition and modernity, is another weight on Turkish mentality. Pamuk speaks of the marriage between passion and fascination. Criticism from Europe angers the Turks and can provoke nationalist reactions, but Turks are looking for the west’s acceptance, to have their European spirit confirmed. Pamuk is the only ardent partisan of Turkey’s accession to the EU, but he had realised that the experiences between Turkey and Europe mean the road is longer and more complex.

Opposites attract

Turkey is also a country where radically opposing ideologies exist. Pamuk says being sidetracked by extremist ideas constitute a passionate Turk, as seen most clearly in Snow (2004), which he himself has called his first and last political book. In the north-eastern town of Kars you can find a hotpot of everything going on all over Turkey, including islamist extremists, secularist partisans, nationalists and western looking nostalgic movements. ‘The tangible sense of sadness which comes from being part of Europe and also having non-European politics,’ is omnipresent in Kars, according to Pamuk. ‘Ideological disputes without results engage the whole of society and exhaust their energy.’ Pamuk demystifies the curses of his country, but he profoundly believes that Turkey and Europe have a future in common.

Images: (cc) Lance Catedral; Pamuk (cc) Renato Guerra; Nisantasi and autostop (cc)CharlesFred/ courtesy of Flickr

Translated from Turcja piórem Orhana Pamuka