Hungary celebrated the 52nd anniversary of the 1956 revolution

Published on

October 23, 2008

On October 23, many Hungarians, all around the country, commemorated their compatriots who fought in the anti-Soviet revolution in 1956. A total of 485 events took place throughout the county. Senior government officials laid wreaths at key sites of the revolution and at the memorial in a public cemetery where martyrs of the revolution were buried in unmarked graves.

Similarly to the last two years, anti-government, mostly far right demonstrators also held their own rallies, but significantly less people participated at their programs this year. In contrast to last year, the events went peacefully and there were no clashes between the police and the far right groups.

The 1956 Hungarian revolution and armed uprising against the domestic Stalinist dictatorship and Soviet occupation started with a peaceful student demonstration on October 23. Tens of thousands of students demonstrated in the streets of Budapest demanding the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Hungary, a government to be formed by reformist communist Imre Nagy, the revision of Soviet-Hungarian relations on the basis of equal rights and non-interference, multi-party elections based on a secret ballot, freedom of expression, and a free radio.

In the evening Ernő Gerő, the arch-Stalinist leader of the ruling Hungarian Working People's Party (MDP), broadcast a harsh and threatening speech over the airwaves refusing to make any concessions. The speech sparked hostilities in the city. During the night, armed groups occupied the headquarters of Hungarian Radio and the communist daily Szabad Nép, the main telephone exchange, the radio transmission tower at Lakihegy on the outskirts of Budapest, several arsenals, military barracks, factories and other facilities.

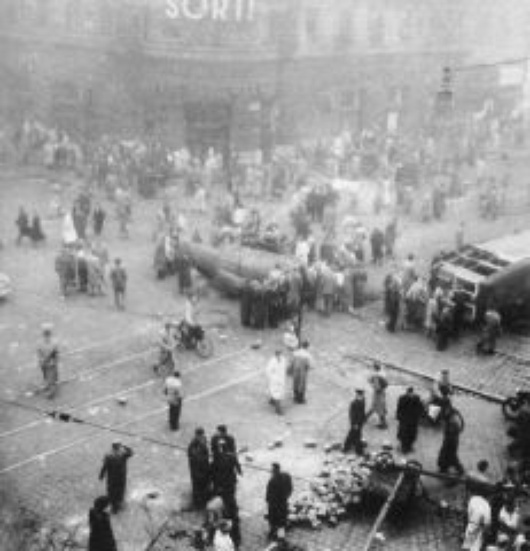

On the city's official parade grounds an enthusiastic crowd toppled the Stalin monument, a hated symbol of tyranny. What started as a peaceful demonstration escalated into a popular uprising in a matter of few hours, and then, after Soviet troops stationed in Hungary were deployed onto the streets of Budapest, into an armed freedom fight.

On the city's official parade grounds an enthusiastic crowd toppled the Stalin monument, a hated symbol of tyranny. What started as a peaceful demonstration escalated into a popular uprising in a matter of few hours, and then, after Soviet troops stationed in Hungary were deployed onto the streets of Budapest, into an armed freedom fight.

Mass demonstrations in Budapest and the countryside claimed many victims. Protesters gathering in front of Parliament on October 25 were fired on from the rooftops of neighboring buildings by a still unidentified unit, killing scores of people. Another volley claimed the lives of 52 victims at the Border Guard barracks at Mosonmagyaróvár, some 10 kilometers from the Austrian border, on October 26. Soviet troops left the cities around this time, but were soon to return.

The siege of MDP's Budapest headquarters was involved bloody atrocities on all sides. After the second Soviet intervention on November 4, shooting in other rural regions claimed several more lives.

The dictatorial regime had been in a state of crisis long before the uprising, marked by events such as the resignation of Mátyás Rákosi, "Stalin's Best Hungarian Disciple", in July 1956 and the reburial of László Rajk and other victims of a Stalinist show trial in early October 1956, just days before the uprising.

From the political point of view, the revolution was controlled by MDP's reform communist wing, first of all by Imre Nagy, who became prime minister on October 24. Initially, Nagy's platform was shared by Janos Kadar, who succeeded Gerő as party chief on October 25.

A flurry of political activity ran throughout the revolution. Several parties and organizations, banned or marginalized by the communists in the late 1940s, re-emerged on the scene. Nagy responded by forming a second coalition government, including politicians of the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party (HSWP, which succeeded MDP), the Independent Smallholders' Party, the Peasant Party and the Social Democratic Party. But the polarized political forces lacked a uniform ideology, and the armed freedom fighters and demonstrators were disparate. What all of them shared were the priorities of restoring national independence and ending the dictatorship.

A flurry of political activity ran throughout the revolution. Several parties and organizations, banned or marginalized by the communists in the late 1940s, re-emerged on the scene. Nagy responded by forming a second coalition government, including politicians of the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party (HSWP, which succeeded MDP), the Independent Smallholders' Party, the Peasant Party and the Social Democratic Party. But the polarized political forces lacked a uniform ideology, and the armed freedom fighters and demonstrators were disparate. What all of them shared were the priorities of restoring national independence and ending the dictatorship.

The Soviet military invasion launched on November 4 sealed the fate of both the freedom fighters and Nagy's government. Kadar himself turned against the revolution and formed a pro-Soviet government, which helped the invading Soviet troops to quell the revolution. The attack started a few days after Nagy declared Hungary's neutrality and withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact. The last pockets of armed resistance were mopped up on November 10-11.

The series of revolutionary events starting on October 23 claimed many victims. According to the Central Statistical Office, from October 23 to January 16, exactly 2,652 people (including 2,045 in Budapest) lost their lives and 19,226 people (including 16,700 in Budapest) were wounded. Official statistics released in 1991 revealed that 669 Soviet soldiers were killed and 51 disappeared during the hostilities.

The series of revolutionary events starting on October 23 claimed many victims. According to the Central Statistical Office, from October 23 to January 16, exactly 2,652 people (including 2,045 in Budapest) lost their lives and 19,226 people (including 16,700 in Budapest) were wounded. Official statistics released in 1991 revealed that 669 Soviet soldiers were killed and 51 disappeared during the hostilities.

The suppression of the revolution was followed by three years of massive retaliation. Tens of thousands of Hungarians were arrested and 220 to 340 of them were executed (source differ in reporting the numbers). Those executed included Imre Nagy, Defense Minister Pal Maléter, pro-reformist journalist Miklós Gimes, Minister of State Géza Losonczy as well as Jozsef Szilagyi, head of Nagy's secretariat. Over 10,000 people were imprisoned or interned, and approximately 200,000 fled the country.

For more than three decades, it was only permitted to refer to the events of 1956 in Hungary as a "counter-revolution". The turning point came about in January 1989 when Imre Pozsgay, a leader of the HSWP, called the events a "popular uprising".

The first measure taken by the first freely elected Parliament convened in 1990 after more than four decades was to enact a law commemorating the 1956 revolution and freedom fight, declaring October 23 a national day.

Addressing the Hungarian Parliament in November 1992, then Russian President Boris Yeltsin apologized to the Hungarian nation for the Soviet intervention. In 2006, members of the Russian Federation Council (upper house) voiced their moral responsibility and regret over what happened 50 years earlier.