How to get to Srebrenica - if it still exists (12 images)

Published on

Translation by:

Alexandra BaxterA town which is now a mountain village, society's memory loss, Iranian connections and a Serbian folk family distraction: an Italian driving to the Bosnian town shares his trip memories

The deafening sound of a brass band echoes along the edge of the country road that leads towards the Bosnian border. I can’t resist the temptation: I brake and get out of my car to take in this folk flavour of Serbia

The festivities are a family event in honour of their son, who is about to leave to do his national service in the army. Musicians and relatives alike come across me and, without so much as a hesitation, invite me to the dinner table to celebrate with them. I sit down and am surrounded by meat and wine. The uncle, sat to one side of me, is holding out a bank note in front of him: he is drinking without even coming up for air, and he refills my glass for me. The father of the young man keeps asking to take a photo of me sitting next to his son

A little while afterwards, the ancient grandmother wriggles round, and throws a bottle of beer on the floor, which shatters into pieces. The shards of glass are not gathered up until the end of the celebrations: this is her way of wishing her grandson good luck.

'Where are you going?' they ask me. 'To the south,' I answer vaguely, 'to visit the orthodox monasteries.' However, my interest lies elsewhere – over the border in Bosnia, in fact. Almost fifteen years after the end of the conflict in the Balkans, there is still much tension between the two nations. However, nobody around here wants to talk about the past, or about the war

Entering Bosnia isn’t as easy as I thought it would be; road maps and guide books are of little use to me. Having left the main route, I climb up into the mountains and finally reach the border. Two little cubby-holes wait for me on the roadside. The bored customs officials let me pass without asking too many questions. As soon as I have crossed the border, I realise that something has changed: the countryside around me is very different from that which I saw in Serbia; the majority of houses still bear their war wounds

There are holes and punctures left by bullets everywhere. It's practically impossible to find a building with its walls intact. Many of the dwellings are little more than tiny mountain cottages. Where people have had the opportunity to rebuild their house, they have done so alongside the original ones which have been destroyed by mortar blows from Serbian and Bosnian artillery

I leaf nervously through the pages of my guidebook. I have a recent edition and it is very up-to-date; surely then there will be directions to Srebrenica, my first port of call

Sadly, this Bosnian town became famous in July 1995 after its muslim community became the object of a brutal ethnic cleansing campaign. The militias of the commander Ratko Mladić, who is currently wanted for crimes against humanity, entered the city, which is officially under the protection of the UN. They gathered together and then massacred all adult muslim males. Official estimates suggest that around 7, 800 men were killed in under ten days. Mladić’s militias succeeded in carrying out their manic operation largely due to the lack of intervention from the UN military contingent: the 450 Dutch soldiers who ought to have guaranteed that the muslim community came to no harm

Despite the importance of the place, Srebrenica seems not to exist; in the guidebooks, I cannot find any information about how to get to the town. There is the odd reference to it in the introductory section on Bosnia, but there is nothing written about the cause of the massacre, let alone the serious failings with which the UN contingent is stained

In order to find a tangible relic of the Srebrenica massacre, you need to leave the town and take the main road to the south. Almost by accident, you come across the memorial of the massacre: a gigantic complex which has not yet been finished, where the bodies of more than five thousand people, not all of them identified, lie buried, one next to the other, under a bare white headstone

With fifteen years gone by since the massacre, many things have changed. The town which I find before me is a mountain village, barely bigger than the others which I have come across up until now. No-one seems to want to remember that sad episode in its history; everyone is keen to get the town back on its feet. The mosque and the madrassa have recently been reconstructed, but the builders are still working to finish the last few details

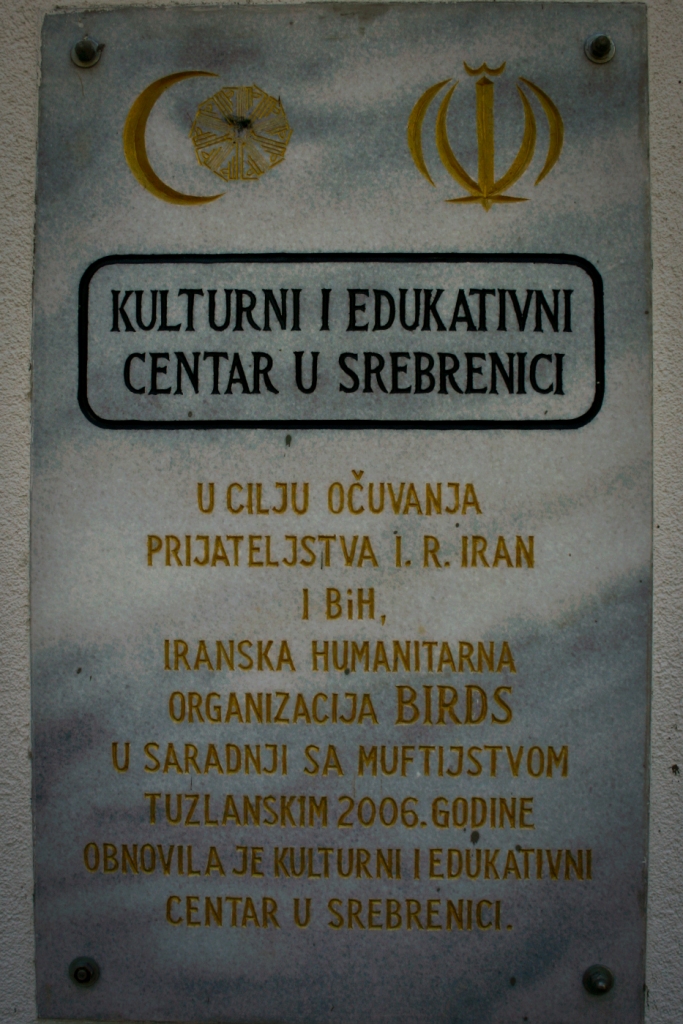

I discover that the reconstruction of the two buildings is being financed not by the EU or the UN, but by an Iranian non-governmental organisation called Birds. Or at least, this is what I gather from the commemorative plaque on the wall of the madrassa. In an internet café in Srebrenica I write various emails to the Iranian embassy to ask for more information about other reconstruction projects in the town, but I get no reply

When I arrive in Sarajevo, I make my way to the Iranian embassy in search of information about the things that I have seen. However, again I find myself in front of a closed door; the embassy of the Middle Eastern state seems completely deserted. When the guard in the gatehouse approaches me and confirms that the diplomatic offices are empty, I am assailed by a sense of nothingness: everyone, from the victims to the murderers, seems to want to forget what has happened all too quickly.

(First published on cafebabel.com on 4 November 2009)

Translated from Srebrenica dimenticata