Hope in 2011: Tahrir and Puerta del Sol utopias

Published on

Translation by:

Annie RutherfordThis time it’s for real. Bad luck for Greece. Thomas has made up his mind: he’s leaving tonight. He climbs into the boat – and goodbye. Between Thomas More’s Utopia and Charles Fourier’s concept of the phalanstery, a literary look back at 2011

Thomas has nightmares. The first night at high sea was awful. He dreamt he was surfing with a wood printing press producing drachmas on enormous debts represented by a sort of wave which made an ‘AAA’ noise. Incomprehensible. When he woke up, Thomas found himself in the middle of Adriatic sea. Finally alone. Finally far away.

Greece is going mad. Suddenly he can see, he can feel. A power like a warm current attracts him. His boat is sucked in by the current. A renewed gust of wind pushes his boat so fast and with so much strength that Thomas is not even able to guess how far it has brought him. Like a magnet he has come all by himself – to the gates of democracy.

Greece is going mad. Suddenly he can see, he can feel. A power like a warm current attracts him. His boat is sucked in by the current. A renewed gust of wind pushes his boat so fast and with so much strength that Thomas is not even able to guess how far it has brought him. Like a magnet he has come all by himself – to the gates of democracy.

Unbelievable. Hoards of people are marching in rows, followed by a wave of individuals: young and old, fat and thin, men and women form a whole. The island in which Thomas is stranded represents tangible desires. An entire people is demonstrating in the name of hope. Their cry prompts overripe fruit to fall from a tree, which becomes more and more majestic as the people march forward. The word ‘Tahrir’ is written on its trunk. A dove sits in the tree’s branches. ‘The one which will bring spring.’

From now on Thomas knows what marks hope out. Hope represents this invisible being. The so-called ‘Tahririans’ almost all recognise a higher being. However, founded on the desire to live according to nature, ‘Tahrir’ is above all for its citizens and against war. It is an island which condemns secrecy, deceit, corruption, personal enrichment and lust. So many things for which the spoilt fruits stand which fall from the royal tree. So much food which has been poisoning its homeland for a long time.

The island ‘Tahrir’ in all its splendour is the glowing counterpoint to Greece. The Tahririan economy is based on the absence of trade, the ban of speculation and the inexistence of lack. This ideal society lives without money. In Thomas’ homeland, people spend their time running after a thing which devalues itself. They attempt to foretell the future every day, using figures and on the orders of people who share the same money but don’t seem to understand it. These people even include others in their club, a devil’s circle of sweet promises of freedom – at least until stricter and stricter rules destroy social codes, strengthen inequality and distance people from each other through five inhumane letters: D-E-B-T-S. As a witness of need Thomas mocks, ‘it is mistaken to think that a people’s suffering guarantees freedom. After all, where do more fights break out than between beggars?’

The island ‘Tahrir’ in all its splendour is the glowing counterpoint to Greece. The Tahririan economy is based on the absence of trade, the ban of speculation and the inexistence of lack. This ideal society lives without money. In Thomas’ homeland, people spend their time running after a thing which devalues itself. They attempt to foretell the future every day, using figures and on the orders of people who share the same money but don’t seem to understand it. These people even include others in their club, a devil’s circle of sweet promises of freedom – at least until stricter and stricter rules destroy social codes, strengthen inequality and distance people from each other through five inhumane letters: D-E-B-T-S. As a witness of need Thomas mocks, ‘it is mistaken to think that a people’s suffering guarantees freedom. After all, where do more fights break out than between beggars?’

There is nothing like this on Tahrir. Tahrir is freedom. Tahrir is the affirmation of the desirable. On leaving, before he reaches the boat, he is filled with this hope. A hope, shared between reality and dream. Never mind, it will stay with him. ‘I am indignant. I firmly believe that things can change. I believe that i can help. I know that we can succeed together. Come with us on the street. That is your right.’

Thomas still has nightmares. He’s still in this state on the second night of his journey, in this state which he cannot describe. He has seen beautiful things. He has grasped hope. Yet can this young majesty be introduced onto the ‘old’ continent? Perhaps not. Nonetheless, you have to be sure of yourself. At dawn a strange music starts up at the bow of his boat. It is as though 60, 000 pairs of hands beat with all their craft at the horror that his land has suffered. Not far away from ‘Tahrir’, the seeds of a new tree of democracy are sown.

The name of the place is ‘Puerta del Sol‘. It is far from ideal. In many ways it is similar to Greece. However, it seems as though an unfaltering group of people want to repay like with like. In fact, what they want is democracy. They once knew a ‘Tahrir’. Today it has been stolen from them. The D-E-B-T-S stole it from them. All they want is to win back real demoracy: here and now. Thomas knows that these people are in the same situation as he is. He has asked. Thomas knows what his situation means. He is an indignant citizen. For six months long he mixes with 400 families united in a type of cooperative hostel in the middle of large, blooming area. Inside, great galleries are created to regulate encounters and traffic. On either sides, rows of workshops are dedicated to fantasy, discussions and writing. A charter emerges from the workshops: the manifesto of the indignants.

The name of the place is ‘Puerta del Sol‘. It is far from ideal. In many ways it is similar to Greece. However, it seems as though an unfaltering group of people want to repay like with like. In fact, what they want is democracy. They once knew a ‘Tahrir’. Today it has been stolen from them. The D-E-B-T-S stole it from them. All they want is to win back real demoracy: here and now. Thomas knows that these people are in the same situation as he is. He has asked. Thomas knows what his situation means. He is an indignant citizen. For six months long he mixes with 400 families united in a type of cooperative hostel in the middle of large, blooming area. Inside, great galleries are created to regulate encounters and traffic. On either sides, rows of workshops are dedicated to fantasy, discussions and writing. A charter emerges from the workshops: the manifesto of the indignants.

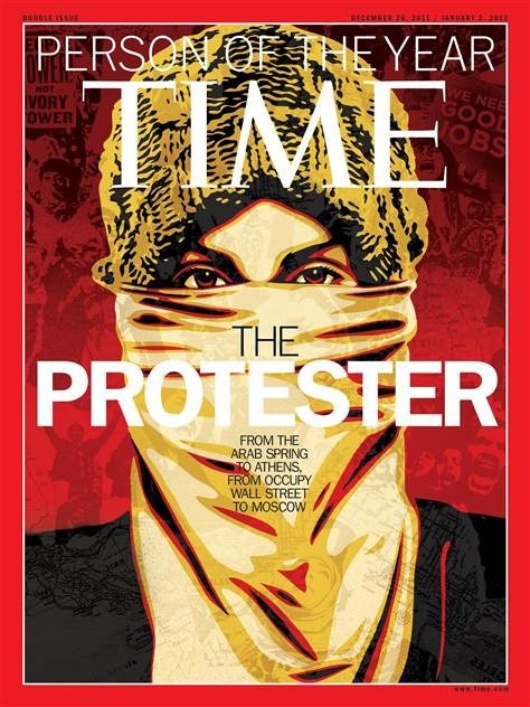

‘The revolution? I wish for it more than I hope for it.‘

Equality, inalienable rights, democracy through the people…these are the values which the ‘ethical revolution’ which Thomas been drawn into points towards. For six months Thomas surfs on hope from all corners of this continent and despite this he is despairing. A revolutionary wind brings him home after a nine month waltz of freedom. Thomas closes his eyes. He doesn’t want to see Greece again. He wants to keep the memories of ‘Tahrir’ and ‘Puerta del Sol’ with closed eyes, these glowing utopian buildings or phalansteries which filled him with hope for almost a year. In order to hope. Still. However, when Thomas opens his eyes, they betray him. He doesn’t believe what he sees. In front of him there is a mighty tree. On its trunk is written in golden letters ‘Syntagma’. At the roots, there is a portrait: the portrait of the person of the year. Thomas rubs his eyes. The picture is of him. Above his face is written: ‘The protester‘. The subtitle: ‘The revolution? I desire it more than I hope for it.‘

Equality, inalienable rights, democracy through the people…these are the values which the ‘ethical revolution’ which Thomas been drawn into points towards. For six months Thomas surfs on hope from all corners of this continent and despite this he is despairing. A revolutionary wind brings him home after a nine month waltz of freedom. Thomas closes his eyes. He doesn’t want to see Greece again. He wants to keep the memories of ‘Tahrir’ and ‘Puerta del Sol’ with closed eyes, these glowing utopian buildings or phalansteries which filled him with hope for almost a year. In order to hope. Still. However, when Thomas opens his eyes, they betray him. He doesn’t believe what he sees. In front of him there is a mighty tree. On its trunk is written in golden letters ‘Syntagma’. At the roots, there is a portrait: the portrait of the person of the year. Thomas rubs his eyes. The picture is of him. Above his face is written: ‘The protester‘. The subtitle: ‘The revolution? I desire it more than I hope for it.‘

Images: main (cc) ; in-text: boat (cc) dimitratzanos; Tahrir (cc) ahmadhammoud, meditation (cc) h.koppdelaney, Puerta del Sol (cc)pasotraspaso, The Protester (cc) newyork music/ all via flickr/ video: CHRISTOPHEB06/ youtube

Translated from L’espoir en 2011 : la possibilité d'une île