Happy as a dog with two tails: Hungary's anti-hate party

Published on

Translation by:

Charlotte WalmsleyOn 2 October, Hungarians will be hitting voting booths in a referendum to accept or reject EU migrant quotas. The government's anti-migrant campaign has had its desired effect: xenophobia, hatred and misinformation are at an all-time high. However, while the opposition party has remained quiet on the issue, a pro-migrant campaign has sprung out of nowhere with boundless optimism and positivity.

In Budapest, immigration is a serious issue. So serious, in fact, that the government has become increasingly unhappy with the EU's decision to use Hungary as a base to redistribute migrants arriving in Europe for the last year and a half. In retaliation, the Hungarian government has called a referendum. Given the question, it is easy to guess the response the government wants from its citizens: "Do you want Brussels to be able to determine immigration policy for non-Hungarians in Hungary, regardless of the will of the Hungarian parliament?" To further clarify the government's stance, Viktor Orbán launched a campaign of fear, using advertising space and posters emblazoned with heavily exaggerated or false information about immigration in Europe and policies from Brussels.

One poster, for example, claims that: "The number of immigrants Brussels wants to send here could fill a city." This could potentially be true if the government meant a village, as the total quota is only 1,300 people. The government has also claimed that: "Perpetrators of the terrorist attack in Paris were migrants," which is blatantly untrue: the attackers were French and Belgian. In other words, the government's campaign against the demonic "migrant quotas" imposed by Brussels has been able to spread misinformation with no holds barred. There is just one problem with this campaign: migrants across the entire country number less than 2,000. What is even stranger, however, is that it hasn't been the opposition party that has fought against this campaign of hatred and violence. That task has instead fallen to a satirical movement, which started 10 years ago as a joke, under the rather bizarre name of Magyar Kétfarkú Kutya Part, or The Dog With Two Tails Party.

A homemade opposition party

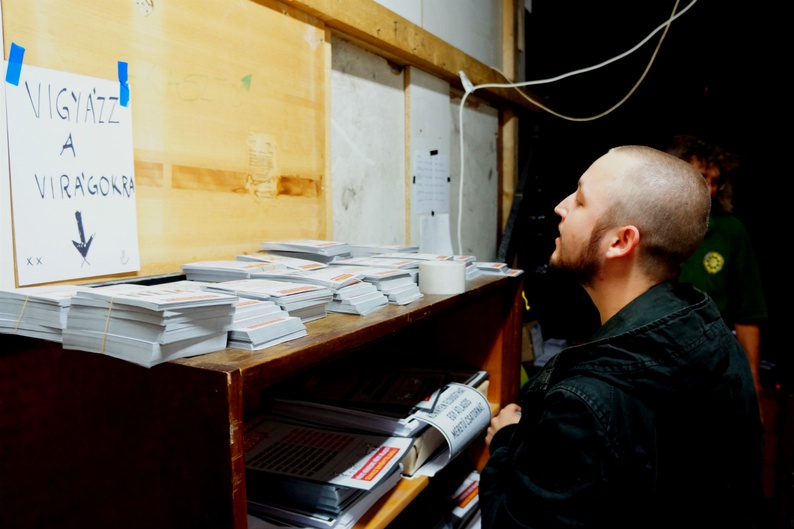

Located in the central Blaha Lujza tér in Budapest, the Muszi is a sort of community centre: a space that's free to rent for local events and boasts an endless list of activities and initiatives held on its premises. The Muszi is now also the headquarters of Kutya Part's campaign against the referendum. The campaign itself is based on a very simple concept: to ridicule and make fun of the government's campaign by creating a parallel campaign with an identical format, using silly messages and caustic slogans to undermine the 'No' campaign's rhetoric. Slogans like: "Did you know that Brussels is a city?" (in reference to the referendum's chosen question, which refers to Brussels and not the EU) and "Did you know that the average Hungarian citizen sees more UFOs in their life than migrants?" have been plastered all over the streets of the Hungarian capital, surpassing the campaign posters used by Orbán and his party in both number and variety. It is at Muszi that these posters are collected and prepared for distribution, in a small storage room that reeks of tobacco, print, paint and glue. Despite their humble headquarters, these posters line the streets of Budapest as volunteers come in droves, taking tens, and sometimes hundreds, to stick up around the city.

Volunteers belong to all age groups and social classes: from young students who come to fill their backpacks, to suited and booted professionals with an empty vacuum cleaner box in one hand and the keys to a Mercedes in the other, to elderly cyclists. All are lending their support to a campaign against government policies of austerity and its campaign of hatred and fear. Among them is János, a 21-year-old Law student: "I think what we are doing here is really useful; humour is a formidable weapon. I think 'No' will win in any case, but this sends an important signal. Not everyone supports the government... there are many of us who don't."

Volunteers belong to all age groups and social classes: from young students who come to fill their backpacks, to suited and booted professionals with an empty vacuum cleaner box in one hand and the keys to a Mercedes in the other, to elderly cyclists. All are lending their support to a campaign against government policies of austerity and its campaign of hatred and fear. Among them is János, a 21-year-old Law student: "I think what we are doing here is really useful; humour is a formidable weapon. I think 'No' will win in any case, but this sends an important signal. Not everyone supports the government... there are many of us who don't."

Irony, beer and economy

Gergely Kovács is the leader of Kutya Part. He is wearing a baggy shirt, sagging trousers, worn tennis shoes and an infectious smile: not exactly the typical portrait of an intellectual political leader. "It all started in 2006, when the election campaign started teasing out empty and earnest partisan promises, such as inventing a party that offered things like free beer and eternal life, if elected," says Kovács.

"Our whole movement is based on the work of about 1,000 volunteers. We only buy what we actually need, from spaces to display our posters to paper to print them on. We are funded by donations and crowdfunding campaigns. Altogether, we have funded about 46 million guilders (about 150,000 euros)," Kovács explains. "The idea behind this initiative basically stems from wanting to fight the government's propaganda of hatred and violence by using its own rhetoric to show how absurd it is," Kovács smiles. He appears relaxed, and talks calmly and ironically of the vision of the movement behind the referendum campaign, as if talking to an old friend. "I believe that this hate campaign, which has lasted around a year and a half, was basically a mistake. A mistake that has, however, cost a lot of money [It is not known how much, as the Hungarian government has not released the costs of the campaign, ed.], and we countered it with a campaign that has apparently only used about 1% of the amount spent by the government. If we had their sort of money, we could rebuild some bus stops or redecorate more street benches. As for the rest, we could spend that on beer for volunteers."

"Our whole movement is based on the work of about 1,000 volunteers. We only buy what we actually need, from spaces to display our posters to paper to print them on. We are funded by donations and crowdfunding campaigns. Altogether, we have funded about 46 million guilders (about 150,000 euros)," Kovács explains. "The idea behind this initiative basically stems from wanting to fight the government's propaganda of hatred and violence by using its own rhetoric to show how absurd it is," Kovács smiles. He appears relaxed, and talks calmly and ironically of the vision of the movement behind the referendum campaign, as if talking to an old friend. "I believe that this hate campaign, which has lasted around a year and a half, was basically a mistake. A mistake that has, however, cost a lot of money [It is not known how much, as the Hungarian government has not released the costs of the campaign, ed.], and we countered it with a campaign that has apparently only used about 1% of the amount spent by the government. If we had their sort of money, we could rebuild some bus stops or redecorate more street benches. As for the rest, we could spend that on beer for volunteers."

A country divided

What is particularly noticeable, wandering through the streets of Budapest, is how little space has been dedicated to reasons to support the 'Yes' campaign. Apart from a handful of Kutya Part posters, there is no sign of life from the opposition. The Hungarian media is on the same wavelength: the topics most frequently discussed on TV are migrants and national security, and these discussions almost uniquely centre on the threat of migrants. If you go to a pub to talk politics and espouse the values of cultural diversity and business-minded reasons to support migration, even amongst friends, you may come across as a dangerous extremist or an ignorant fool who does not care about the future of Hungary and its people. Although the actual numbers paint a much less apocalyptic picture, the government's propaganda of fear has been very effective. The vote is already being heralded as a hands-down victory for the 'No' campaign.

Hungary appears to be a country split in two. On one side are followers of the traditional media, which is almost completely controlled more or less directly by the government to spread positive propaganda about their policies. On the other are people who look for alternative news sources, which can be a task that requires a lot of perseverance. It is a country that is going to the polls distracted by the multitude of issues it faces - scandals, a sluggish economy, rampant poverty in certain areas of the country - alongside its "sacrifices" in the name of fighting the bogeyman of illegal immigration and pressure from Brussels. "We're always talking about immigrants and immigration, but we don't have a referendum on the real issues that affect us," says Kovács. "For example, Budapest's candidacy for hosting the 2024 Olympic Games. We cannot afford it, but it's great propaganda. I would like to see how many would say yes to a referendum on that."

Hungary appears to be a country split in two. On one side are followers of the traditional media, which is almost completely controlled more or less directly by the government to spread positive propaganda about their policies. On the other are people who look for alternative news sources, which can be a task that requires a lot of perseverance. It is a country that is going to the polls distracted by the multitude of issues it faces - scandals, a sluggish economy, rampant poverty in certain areas of the country - alongside its "sacrifices" in the name of fighting the bogeyman of illegal immigration and pressure from Brussels. "We're always talking about immigrants and immigration, but we don't have a referendum on the real issues that affect us," says Kovács. "For example, Budapest's candidacy for hosting the 2024 Olympic Games. We cannot afford it, but it's great propaganda. I would like to see how many would say yes to a referendum on that."

Be positive!

"The truth is that we do not specifically campaign about immigration and migrants. What we are against is the government’s campaign of hatred and violence. I think that we Hungarians hate each other enough already, so more hatred is really the last thing we need in our society, "says Kovács. "Although perhaps it is good that all this violence is focused on migrants: here there aren't any, so there is no danger really," he adds, with a provocative smile.

So, what can we take from this satirical movement, which was born of a joke? Considering the fact that the Kutya Part has been the only political force that has countered the Prime Minister's nationalist rhetoric regarding the migrant question (the opposition was so limited as to not even adopt a contrary position) and also considering that it enjoys broad support in the capital (which alone accounts for more than 1/10 of the Hungarian electorate), in the cafes and cultural circles of the city many are wondering what would happen if Kovács officially entered the political arena and challenged Orbán at the 2018 general election. "What will I do after this referendum? I'll sleep for a week, no doubt!", confesses Kovács, laughing jovially. He then responds seriously: "we know that we have some support here in Budapest, with many people who would be candidates and who would vote for us. However, it's not really the most important thing to think about at the moment. It's early days."

So, what can we take from this satirical movement, which was born of a joke? Considering the fact that the Kutya Part has been the only political force that has countered the Prime Minister's nationalist rhetoric regarding the migrant question (the opposition was so limited as to not even adopt a contrary position) and also considering that it enjoys broad support in the capital (which alone accounts for more than 1/10 of the Hungarian electorate), in the cafes and cultural circles of the city many are wondering what would happen if Kovács officially entered the political arena and challenged Orbán at the 2018 general election. "What will I do after this referendum? I'll sleep for a week, no doubt!", confesses Kovács, laughing jovially. He then responds seriously: "we know that we have some support here in Budapest, with many people who would be candidates and who would vote for us. However, it's not really the most important thing to think about at the moment. It's early days."

But why is the party calle The Dog with Two Tails Party? "The idea came from an old English saying: when a dog is happy, he wags his tail so fast that he seems to have two tails. This was the exact message that we wanted to spread: happiness and positivity."

This kind of positivity is exactly what Hungary needs, now more than ever.

Translated from Referendum in Ungheria: l'opposizione è un Cane a Due Code