Hand-shaking for Ukraine VS endless waiting for Ukrainian citizens

Published on

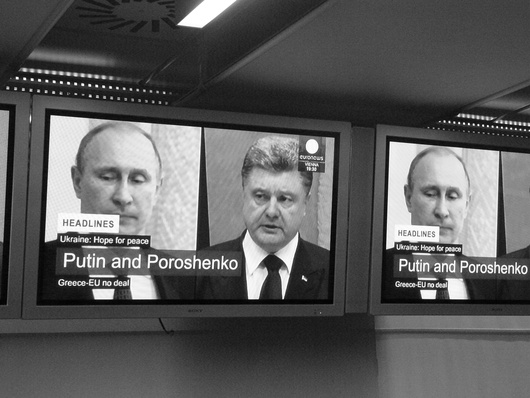

Tension had already accrued all the way from Belarus in the Council's atrium as the heads of states and governments eventually emerged. The agenda of the European Council's informal meeting of 12th of February, initially meant to address anti-terrorism measures and stumbling blocks of the Euro, ended up being overshadowed by pressing international matters, among which peace-brokering in Ukraine.

After all-night negotiations in Minsk, some serious mutual back-patting unfolded in Brussels. The new package of measures aimed at ending the current war in Ukraine or the so-called Minsk II agreement, which was agreed by representatives of Russia, Ukraine and the separatist regions of Lugansk and Donetsk, was repeatedly mentioned in press conferences that followed the Council.

Calm and European unity at the Council: the Franco-German couple at its peak

Called at times “second-best option (…) a reasonably dignified way out of the crisis” or “beacon of hope”, Minsk II triggered at best some “realism tinged with relief”. European leaders appeared both calm and tired, but jointly praised their proactive benevolence. While European Parliament President Martin Schulz underlined the “constructive atmosphere” that dominated current talks and the “good sign” beckoned by such cooperation "among Europeans”, President of the European Council Donald Tusk thanked Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President François Hollande for their “indispensable efforts for peace in Ukraine”. Ukrainian President Poroshenko corroborated these words by declaring that there were reasons for “careful optimism”.

Called at times “second-best option (…) a reasonably dignified way out of the crisis” or “beacon of hope”, Minsk II triggered at best some “realism tinged with relief”. European leaders appeared both calm and tired, but jointly praised their proactive benevolence. While European Parliament President Martin Schulz underlined the “constructive atmosphere” that dominated current talks and the “good sign” beckoned by such cooperation "among Europeans”, President of the European Council Donald Tusk thanked Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President François Hollande for their “indispensable efforts for peace in Ukraine”. Ukrainian President Poroshenko corroborated these words by declaring that there were reasons for “careful optimism”.

If European leaders’ concerted efforts and solidarity were emphasised, the long-lasting Franco-German friendship was also once more put to the fore. Merkel stated that it was “good” that “France and Germany are supporting each other”, whilst Hollande, referring back to the Elysée treaty, insisted that their bilateral cooperation was not only “an evocation of the past” and that they had “found their way to each other” in lieu of the Minsk II agreement. So much for the Weimar triangle: resolving yet another delicate crisis proves to constitute another forum allowing France and Germany to shine side by side.

If European leaders’ concerted efforts and solidarity were emphasised, the long-lasting Franco-German friendship was also once more put to the fore. Merkel stated that it was “good” that “France and Germany are supporting each other”, whilst Hollande, referring back to the Elysée treaty, insisted that their bilateral cooperation was not only “an evocation of the past” and that they had “found their way to each other” in lieu of the Minsk II agreement. So much for the Weimar triangle: resolving yet another delicate crisis proves to constitute another forum allowing France and Germany to shine side by side.

Broader context of the Minsk II agreement

At her press conference, Merkel kept a solemn and concerned tone whilst emphasising the key issues of constitutional reform in Ukraine, border control and the necessary decentralisation and specific rule-setting for separatist Republics in the East. She concluded by asserting that she was "concentrated" and laughingly that "the week is not over yet".

The imperfect agreement reached in Minsk comes in after well over a year of a dangerously escalating conflict and after the Minsk I protocol, which clearly failed to deliver due to blunt non compliance. Hence, pressure to deliver has never been that high as no further violence can be accepted. But what is also at non immediate stake here are the efforts engaged both by Ukraine and the EU to increase their multilevel cooperation, notably through various projects initiated and financed under the Eastern Partnership. Certainly, this political initiative is sensibly ridiculed in face of Russia’s much more immediate and aggressive demeanour.

Some underlying contentious issues

Significant challenges that stand out include the status and political future of the self-proclaimed Republics in the Eastern region of Ukraine, who are concerned by securing financial support from Russia, and where Ukrainian President Poroshenko has little interest in seeing local elections organised. The hybrid situation these territories have been entrenched in is a component of the conflict that complicates any agreement, causing deeper and more complex disconnections in an already deeply divided country. What’s more, the focus on preventing the Ukrainian economy from collapsing, though necessary, seems insufficient and raises uncertainty as to how the International Monetary Fund (IMF)’s financial package will actually be used and at what costs.

Significant challenges that stand out include the status and political future of the self-proclaimed Republics in the Eastern region of Ukraine, who are concerned by securing financial support from Russia, and where Ukrainian President Poroshenko has little interest in seeing local elections organised. The hybrid situation these territories have been entrenched in is a component of the conflict that complicates any agreement, causing deeper and more complex disconnections in an already deeply divided country. What’s more, the focus on preventing the Ukrainian economy from collapsing, though necessary, seems insufficient and raises uncertainty as to how the International Monetary Fund (IMF)’s financial package will actually be used and at what costs.

A flawed agreement sustaining great ambiguities

Already shortly after the cease fire was declared, violations on both sides were declared. Talking about the evident risk of non compliance now thus appears as obsolete. One of the initial uncertainties around the agreement was the undefined signatories and the absence of clear enforcement means by a third party. Another shortcoming is the questions of what further actions European leaders should undertake if the agreement is not respected- at least in its main parts. Additionally, the question of setting further sanctions on Russia and of their efficiency will have to be raised again.

Peace in Ukraine becomes even more dubious when considering that precisely while a cease-fire was being discussed in Minsk, the biggest irony of it all was exposed: British-Russian political activist Natalia Pelevine posted a video on her facebook profile showing a tent in Moscow’s city centre aimed at recruiting volunteers to go to war in Ukraine. With arousing banners reading “Tomorrow Russia will be bigger. Today, you are responsible of how bigger it will be”, or “Novorossia will obligatorily become a part of Russia and then the whole of Ukraine. Are you going to leave all the glory to others?”; “Participate personally. Become a volunteer”. Such proselytism seems simply unbearably provocative.

Talking with a Ukrainian citizen on the Minsk II agreement and more

But how is this high-level political agreement perceived by Ukrainian citizens, who have already endured tenacious hardship and who are faced everyday with the immediacy of a disastrous and still violent conflict, which induces increasingly worrying humanitarian conditions on the ground?

Discussing this with a Ukrainian friend, she argued: “The consensus is not bad, because the alternative in the form of fast conflict escalation is horrifying”, adding that “Western sanctions aggravate Russia’s position against energy resources’ prices slump background”. In her words, the agreement arguably sets Russian and Ukrainian leaders in delicate positions as “they are both clearly dependent on public opinion”. Ukrainian leaders might thus be blamed for “something that people are taught by the media to consider as a defeat”. Republics’ leaders might not be able to stop a battle under Debaltsevo, as military groups commanders who are rather autonomous, have lost a lot of people as well as Ukrainians”, thus all of them “may be tempted to continue military confrontation”. She also underlined the number of technical details in the agreement that have been “deliberately omitted”, which leaves the document itself “opened for various manipulations for all sides of the conflict”.

Discussing this with a Ukrainian friend, she argued: “The consensus is not bad, because the alternative in the form of fast conflict escalation is horrifying”, adding that “Western sanctions aggravate Russia’s position against energy resources’ prices slump background”. In her words, the agreement arguably sets Russian and Ukrainian leaders in delicate positions as “they are both clearly dependent on public opinion”. Ukrainian leaders might thus be blamed for “something that people are taught by the media to consider as a defeat”. Republics’ leaders might not be able to stop a battle under Debaltsevo, as military groups commanders who are rather autonomous, have lost a lot of people as well as Ukrainians”, thus all of them “may be tempted to continue military confrontation”. She also underlined the number of technical details in the agreement that have been “deliberately omitted”, which leaves the document itself “opened for various manipulations for all sides of the conflict”.

What my friend also told me about, which goes well beyond such high-level compromises, is that people in Ukraine are getting used to the situation the country has been falling into in such a vertiginous way. And this is the sober story of fear, of famine. From appalling pictures of Donetsk’s airport before- and after the armed conflict to the half-abandoned city of Debaltsevo, haunting images are countless. In parallel, daily tragedies unfold: "thousands homeless people, broken lives, crippled soldiers forced to fight for scanty money, etc".

The humanitarian situation on the ground is also continuously worsening. Ukrainian pensioners don’t receive their pensions unless registering personally and settling on Ukrainian territory, state aid is “miserable” and many citizens encounter problems to rent apartments. Social tension also accumulates as in my friend’s view, “people in Ukraine have little compassion for internally displaced people", a merit of the “free Ukrainian media” according to her.

Meanwhile, European leaders will remain on the watch out for signs of pacification in Ukraine.