Greeks Forced to Go on a Mediterranean Diet

Published on

Greece was hit hard by austerity measures after the economic crisis in 2008 — even its legendary food market suffered. Belts tightened, Greeks returned to their culinary roots to rediscover the Mediterranean Diet.

Europe as a whole has been tightening its belt with the implementation of austerity measures. To find a way out of the economic crisis, Greece has made some rediscoveries that might help. This is most evident in the food market, where the Mediterranean diet has become a popular approach to battling high unemployment rates on one hand, and securing cash flow to domestic markets on the other. The primary staples of the Mediterranean diet, which is a modern form of traditional Greek, southern Italian and Spanish diets, consist of olive oil, legumes, cereals, fruits, vegetables, fish, cheese, yogurt and wine. Greece took this diet and turned it into a movement, one that is currently booming in the capital city of Athens.

Nothin’ like Mum’s cookin’

Restaurants are now catering to people’s desire for the nostalgia of homemade and traditional food. Places with names such as Mother’s kitchen, Mum’s Grill or Family Diner, now litter the Athenian landscape. Their goal is to preserve the bond between mother and child. “I have a friend from Crete, who now lives in Athens. But her mom still cooks for her and sends her food every week by boat, which takes nine hours to arrive,” says Niki Papalexopoulou, student and official guide at the Museum of Greek Gastronomy in Athens. The museum opened just a few months ago with an exhibition devoted to the monks living on Mount Athos and their Mediterranean diet. According to them, there are only three basic ingredients necessary for life: bread, olive oil and wine. “They produce their own food there. But keep in mind that only men live on Mount Athos and that female animals aren’t allowed up there. So, they have to import dairy products, eggs and so forth.” The current exhibition, which is devoted to Greek products and their use in revised traditional recipes, is representative of the phenomenon taking hold of Greece. “The economic crisis helped Greeks find their way back to local cuisines.”

Restaurants are now catering to people’s desire for the nostalgia of homemade and traditional food. Places with names such as Mother’s kitchen, Mum’s Grill or Family Diner, now litter the Athenian landscape. Their goal is to preserve the bond between mother and child. “I have a friend from Crete, who now lives in Athens. But her mom still cooks for her and sends her food every week by boat, which takes nine hours to arrive,” says Niki Papalexopoulou, student and official guide at the Museum of Greek Gastronomy in Athens. The museum opened just a few months ago with an exhibition devoted to the monks living on Mount Athos and their Mediterranean diet. According to them, there are only three basic ingredients necessary for life: bread, olive oil and wine. “They produce their own food there. But keep in mind that only men live on Mount Athos and that female animals aren’t allowed up there. So, they have to import dairy products, eggs and so forth.” The current exhibition, which is devoted to Greek products and their use in revised traditional recipes, is representative of the phenomenon taking hold of Greece. “The economic crisis helped Greeks find their way back to local cuisines.”

Made in Greece

Food makes up one third of the 15 most exported items from Greece. Food and beverage exports in 2013 were valued at 3 billion euros. Fresh fish, pure olive oil, fruits and nuts, vegetables and cheese are the top five commodities, culminating in 6% of all Greek exports. Most of these have bestowed Greece international recognition. But, what does the Made in Greece label signify today? According to organisers of Food Expo Greece, whose second convention will take place in March 2015 in Athens, organisations such as Made in Greece are a platform for promoting Greek products around the world and attracting international customers. Other online projects include Cookisto and e-FOOD.gr.

Food makes up one third of the 15 most exported items from Greece. Food and beverage exports in 2013 were valued at 3 billion euros. Fresh fish, pure olive oil, fruits and nuts, vegetables and cheese are the top five commodities, culminating in 6% of all Greek exports. Most of these have bestowed Greece international recognition. But, what does the Made in Greece label signify today? According to organisers of Food Expo Greece, whose second convention will take place in March 2015 in Athens, organisations such as Made in Greece are a platform for promoting Greek products around the world and attracting international customers. Other online projects include Cookisto and e-FOOD.gr.

Tradition with a modern flair

Alexandros Charalabopoulos, the head chef at the Titania Hotel in central Athens, also felt the need for changes in catering, and brought reintroduced local Greek products to his dishes. His menu, which is called Made in Greece, is now attracting tourists and locals to the hotel restaurant. “After the crisis, Greeks wanted to help Greek producers by buying their products, but they couldn’t find them anywhere on the market. Sometimes they didn’t even know they existed. So when I came to the hotel, I wanted to create a Greek menu that consisted only of products produced in Greece.” When he introduced his idea to the hotel management, they were immediately on board.

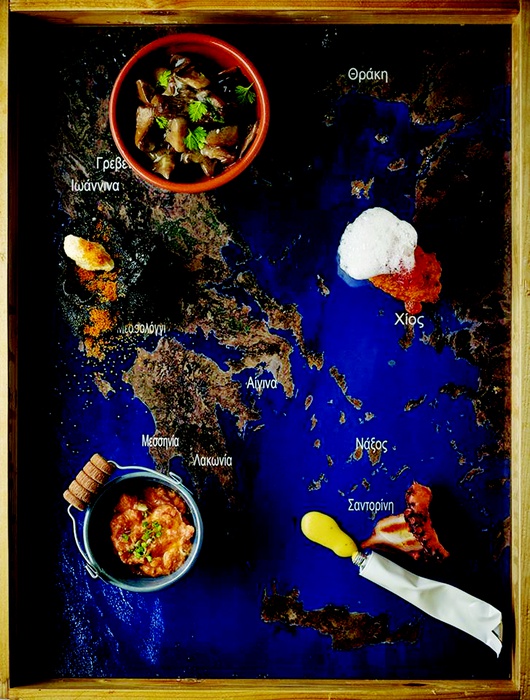

Then, Alexandros set out on a tour around Greece in search of ingredients. “I do not come from Athens. I was born in a small village close to Kalamata in southern Peloponnese. My childhood memories are linked with products that my grandmother used, mostly from small local farmers. So, I started to search there. I wanted to bring my memories back to life,” says Charalabopoulos, whose masterpiece 10-dish menu contains olive oil from Kalamata, potatoes from Nevrokopi, eggplant from Leonidion, bottargo from Messolonghi and xinomyzithra cheese from Crete.

Then, Alexandros set out on a tour around Greece in search of ingredients. “I do not come from Athens. I was born in a small village close to Kalamata in southern Peloponnese. My childhood memories are linked with products that my grandmother used, mostly from small local farmers. So, I started to search there. I wanted to bring my memories back to life,” says Charalabopoulos, whose masterpiece 10-dish menu contains olive oil from Kalamata, potatoes from Nevrokopi, eggplant from Leonidion, bottargo from Messolonghi and xinomyzithra cheese from Crete.

In contrast to the four-star hotel, the restaurant by the name of Two Doors is just a short walk away from the main food market in Athens. The owners have been running their business on the same concept for the past 150 years. The locals call this concept magirio, a reference to homemade food. It is a practice that goes far back in history, and is now trending in Athens.

“The cook prepares several dishes of simple foods and serves them to customers. There is no menu. You see the food in front of you and you choose from what has been prepared,” says Thodorakis, a waiter at a opened restaurant on Aiolou Street. Although the boom in entrepreneurship that the economic crisis caused may seem surprising, its success is not. If you take a stroll around Monastiraki, or climb up Emmanouil Mpenaki Street, you will see brand new restaurants and cafés buzzing with life, most of them offering Greek dishes, either entirely traditional, or traditional with a modern flair. Greeks are proud of their cuisine, and rightfully so, because although they’re on a diet, they know how to enjoy themselves.

THIS ARTICLE IS PART OF A SPECIAL ISSUE DEDICATED TO ATHENS AND IS PART OF THE EU-IN-MOTION PROJECT INITIATED BY CAFÉBABEL WITH THE SUPPORT OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE HIPPOCRÈNE FOUNDATION.